Editor’s note: Will Sacramento council spend more money on community programs to prevent gang violence?

When Mayor Darrell Steinberg started the big police reform meeting on July 1 with a report on rising gang violence, several critics accused him of trying to justify the Sacramento Police Department budget and blunt the calls to “Defund the Police.”

He replied that he wanted to highlight the issue to invest more in anti-gang efforts. The follow-through came July 21 when the City Council gave marching orders on immediate and longer-term funding of violence prevention program.

Council members heard from the Black Child Legacy Campaign, which with more than 50 community partners has been asking since May for $2 million in federal stimulus money: $1.5 million for prevention, intervention and disruption efforts, plus $500,000 for youth workforce and economic development.

Council members pledged to find the money and praised the campaign for its work. “We do see you,” said Councilman Rick Jennings. “We’re making an commitment to invest.”

“We will try to get this money out as quickly as possible,” said Steinberg, who called those doing the work in the community the “real heroes.”

On July 28, the council gave final approval to the $2 million contract through the end of 2020 with the Black Child Legacy Campaign, with $750,000 from the city’s gang prevention task force and $1.25 million from the city’s share of federal coronavirus relief.

Advocates say the need for urgent action on violence prevention is only growing as the COVID-19 pandemic worsens, the economy struggles and tensions rise during what looks like a long, hot summer. In a presentation to the council detailing the work they’re already doing in neighborhoods, they warn of rising costs in lives and economic damage without more intervention and investment.

“It is beyond 911 status. It’s an all-out gang war,” said Kindra Montgomery-Block, associate director for community and economic development with The Center at Sierra Health Foundation, which manages the Black Child Legacy Campaign.

“This is not something the police can handle by themselves. It takes community folks,” she told me Monday.

While stay-at-home orders and other public health measures are needed to stop the virus from spreading, coronavirus is hurting vulnerable neighborhoods in other ways, Montgomery-Block said.

“We have lost more young people to gun violence than COVID,” she said. “It is Black and Brown young people who are dying. Whether they’re 12 or 24, it’s still a young person.”

With the money, she and leaders of the other community groups say they can build on the successful record of 30 months, as of mid-July, without a single youth homicide in Sacramento. That was after 114 teenagers were killed by violence in Sacramento County between 2007 and 2017.

Montgomery-Block points out that the mayor and city council members—who met Tuesday after a three-week recess—have already set aside $15 million of the federal money for loans to small business, plus $7.5 million for grants to arts, cultural and tourism groups.

On the other hand, she said, since the Black Child Legacy Campaign and its partners sent the May 29 letter to the city seeking the $2 million, they have been stuck in bureaucratic red tape—which she blames in part on “structural racism” at City Hall.

“It’s an incredible injustice, it’s an incredible sense of failure,” she said.

And that $2 million is a drop in the bucket compared to the $157 million budget for the Police Department in 2020-21. While Steinberg says he’s not on board with “Defund the Police,” these community violence prevention programs are exactly what the movement has in mind.

Flojaune Cofer—chairperson of the Measure U Community Advisory Committee and among those who called out the mayor for the gang report—argues that the city should invest far more money into these kinds of community programs, and far less into the police department, because they have been far more effective in preventing violence.

On Monday evening, the committee voted to officially recommend to the City Council that it reallocate Measure U sales taxes in 2020-21. The police department would lose all its $41.7 million in Measure U money, while economic development programs would get $33 million more and programs to address homelessness and affordable housing an additional $14 million.

Cofer called it a first step in getting the council to question the status quo in city spending.

She and others say that spending on community programs will save lives and tax dollars by preventing violence before it happens.

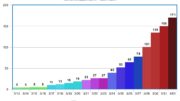

The police department blames gangs, in part, for a recent spike in shootings that has resulted in 28 homicides this year as of July 16, compared to 19 at the same point last year. (Sacramento isn’t alone; there has been a recent surge of deadly violence in cities across the country).

“We have lost more young people to gun violence than COVID. It is Black and Brown young people who are dying. Whether they’re 12 or 24, it’s still a young person.”

Kindra Montgomery-Block, associate director for community and economic development at The Center at Sierra Health Foundation, which manages the Black Child Legacy Campaign.

Besides more effective community programs, Sacramento needs a more comprehensive strategy on gangs that calls in the entire community—schools, nonprofits, law enforcement, government, houses of worship.

Instead, the city’s efforts have been somewhat haphazard over the years.

In 2010, the Ceasefire program came to Sacramento after success in Boston. Ministers led night walks in South Sacramento. Clergy and police met gang members and gave them a choice—go into job training and education or get arrested and put in prison.

Ceasefire produced some encouraging results, but state and federal funding ran out and it lost support from top police officials. In 2013, the city rejected a proposal from the local Ceasefire partnership to expand the program to Del Paso Heights and Oak Park.

Then in 2017, Advance Peace arrived in Sacramento off success in Richmond, in the Bay Area. It also came with controversy because one part of the program is to pay stipends to participants—which critics called paying off criminals.

Still, the council agreed to put in $1.5 million over four years. Now, despite the record on youth homicides, the council is asking for more proof that Advance Peace works before renewing the contract. Tuesday, program leaders are to give an update to council members.

Police Chief Daniel Hahn has given measured support to Advance Peace, saying that he agrees with its premise that a relatively few young men are responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime and that he’s not opposed to paying gang members for reaching goals such as a high school diploma.

Hahn also says there isn’t “one magic solution” to reduce gang violence.

If that’s the case, then doesn’t it make sense to spread money around to different community programs? Now seems like a very good time to make at least a down payment.

Absurd. If people believe that they are doing rotten things, all that they have to do is stop doing what they are doing. Social programs, cop defunding, or other fairy tales are going to stop them? HM