Already stark conditions have worsened under COVID-19

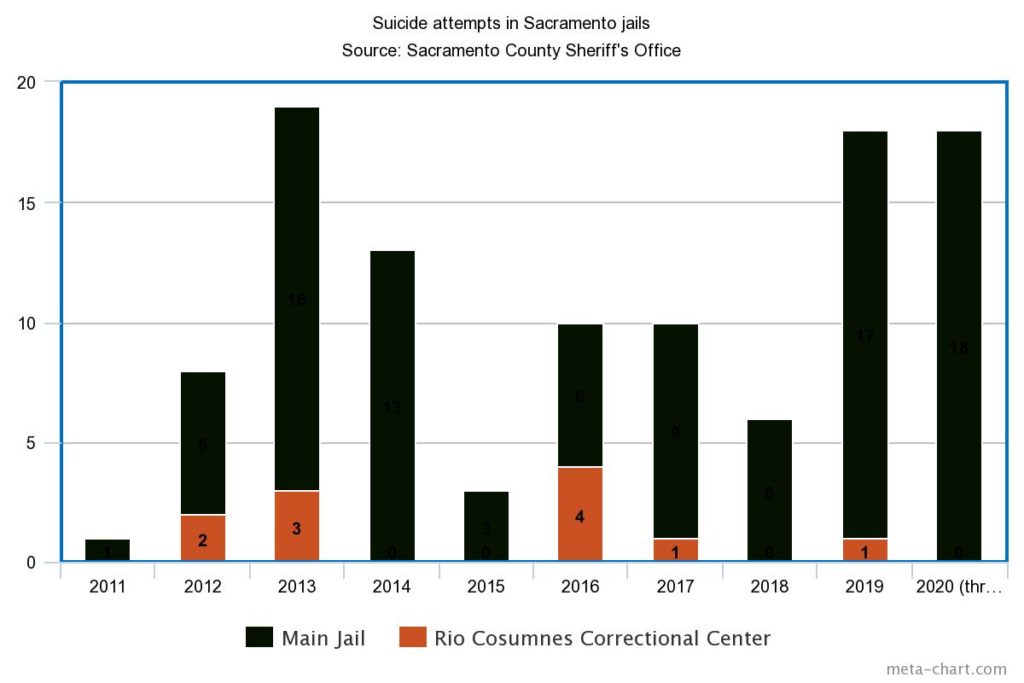

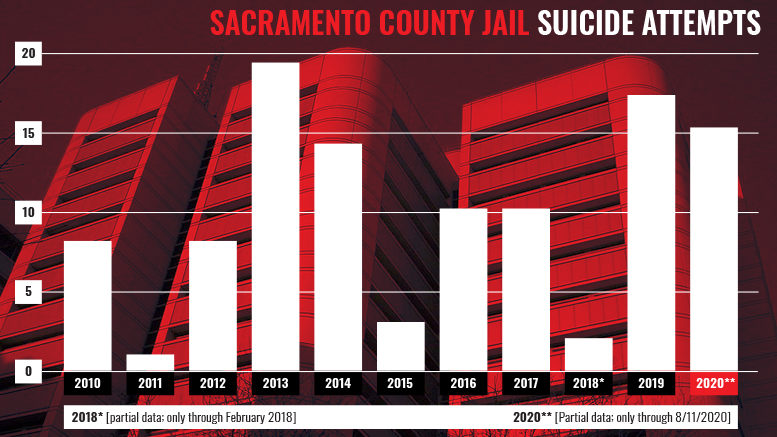

At least 18 people tried to kill themselves in the downtown Sacramento jail this year—breaking last year’s record and underscoring concerns that sheriff’s officials are relying heavily on solitary confinement to avoid a coronavirus outbreak behind bars.

The number of suicide attempts puts the jail system on pace to exceed previous records even as the jail population has declined more than 30% during the pandemic.

The Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office recorded 18 suicide attempts this year through Aug. 31 at the main jail downtown. The sheriff’s office also runs the Rio Cosumnes Correctional Center on the outskirts of Elk Grove.

Dating back to 2008, the previous high was 19 attempted suicides in 2013, though three of those occurred at Rio Cosumnes. According to 12 years’ worth of data that SN&R obtained through public records requests, the jails logged 18 attempted suicides last year and six in 2018. All but one occurred at the main jail.

A sheriff’s spokesman says the numbers reflect a sharp increase in inmates with psychiatric needs, while local inmate advocates and defense attorneys say the coronavirus has only worsened conditions inside Sacramento’s central lockup and further exposed the folly of confining the sick.

“You can’t adequately provide mental health care inside a cell,” said Tifanei Ressl-Moyer, an attorney with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and a founding member of Decarcerate Sacramento, a coalition that wants to reduce the jail population and redirect funding from the sheriff’s office to community-based services.

Yet treating mental illness behind bars is exactly what the county committed to last year, after settling a federal class-action lawsuit that alleged inhumane conditions in the jails. The county estimates $100 million in construction costs to add a psychiatric wing to the main jail and an additional $50 million annually to staff and secure it.

But advocates for the incarcerated worry that the sheriff’s office is turning its failure to protect those in its care into a profitable opportunity.

“We keep hearing from the county about their commitment about caring for people who are inside the jail,” Ressl-Moyer said. “But what we hear from people inside the jail is that they’re not being cared for.

“To see the numbers reflecting that is really hard to stomach.”

While the majority of suicide attempts inside the jail are unsuccessful, the rising numbers over the past two years signal a crisis of desperation for those serving local sentences or awaiting trial.

Pamela Emanuel has witnessed some of the stories behind the statistics.

‘We mean nothing to these people’

Emanuel spent 37 months in Sacramento jail, including the period during which COVID-19 emerged as a health threat. On Aug. 30, she told participants in a Decarcerate Sacramento online forum that guards treated her and her fellow inmates as subhuman, serving them spoiled food, laughing at those with mental illnesses and ignoring urgent medical requests, sometimes with fatal consequences.

“I watched two people die when I was there,” Emanuel said. “It makes no sense for inmates to be treated like we’re animals. Like literally, we mean nothing to these people.”

This is not a new complaint.

Years before the pandemic, prisoner rights’ advocates, attorneys and private consultants warned the county that the local jail system was driving toward catastrophe because of its over-reliance on solitary confinement, chronic understaffing, inmate neglect and an ailing population.

While county and sheriff’s officials acknowledged some of the problems, they deemed the solutions too expensive, leading to a 2018 class-action lawsuit that settled last year with a binding consent decree. The decree requires the jail system to overhaul its delivery of medical and psychiatric care, as well as address concerns over excessive solitary confinement for inmates with special needs.

But COVID-19 has turned the legal process upside down and complicated the time line for certain benchmarks to be met.

“With few exceptions, we’re still at the starting line of implementation,” acknowledged Aaron Fischer, an attorney with Disability Rights California, one of the groups behind the class action.

In court appearances and interviews since March, defense attorneys described how their clients were ordered to spend weeks quarantining in segregated cells upon being booked into jail. Inmates placed on administrative segregation or in “total separation,” which is how the sheriff’s office characterizes solitary confinement, spend nearly 24 hours a day in their cells.

A defense attorney who handles mostly serious misdemeanors and low-level felonies said one client was initially ordered to spend 28 days in isolation because he came into the jail with an autoimmune order.

“He was basically locked up in isolation for having a medical condition,” said Matthew Becker, the man’s attorney. “This is during [the] COVID era.”

A judge released Becker’s client after he spent seven days in solitary, the lawyer said. “The judges are being fairly reasonable during the coronavirus era,” Becker told SN&R. “The Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department is not.”

Meanwhile, the county recently saw the departure of the jail’s medical director, after disclosing in a July progress report to the federal court overseeing the consent decree that it was experiencing “a significant workforce shortage” among correctional nurses and health-care providers.

If anything, the brink has crept closer. And the only people left to ensure the jail doesn’t topple over it are a group of guards who, in Emanuel’s estimation, enjoy when inmates suffer.

Haunted by her memories

In her August video appearance, Emanuel didn’t say when she was admitted to the jail, but remembered a female inmate dying of a drug overdose soon after.

She also recalled a female inmate “with the mind of a child,” crying for her mother while locked in administrative segregation for five days. Another woman spent six months in administrative segregation, a form of solitary confinement that’s typically used for disciplinary reasons, waiting for a bed to open up at Napa State Hospital.

Emanuel said a woman she befriended in the jail died when her repeated complaints of worsening chest pain went ignored. The former inmate broke down remembering the woman’s limp feet dragging against the floor as her jailers pulled her in a shoddy wheelchair. It was the last time Emanuel saw her friend.

“She cried for help. She did everything that they told her to do. To the letter. And these people did not care,” Emanuel said as her daughter stroked her back.

One of Emanuel’s most disturbing accounts concerned another inmate, someone she described as a fun-loving mother, who quickly deteriorated under a severe mental illness.

Emanuel said the woman appeared to develop multiple personalities and began smearing feces on herself and eating it instead of her food. Emanuel said the guards laughed at the inmates’ pleas to help her.

“It wasn’t funny to any of us,” she said.

After three days of allowing the behavior, Emanuel said, two guards pretzeled the soiled woman’s arms behind her and walked her upstairs to a cell, where she continued deteriorating until a concerned female officer learned of the situation and intervened.

According to a January survey, a quarter of the jail population has a serious mental illness.

“The reality was that these people were not OK,” Emanuel said.

Approaching a dangerous record

In total, at least 87 jail occupants have tried killing themselves under Sheriff Scott Jones, who took office in December 2010.

More than 40% of those attempts occurred over the past 20 months.

“Those numbers aren’t surprising,” Decarcerate’s Ressl-Moyer said. “Those numbers reflect that people are deteriorating.”

In an emailed statement, sheriff’s spokesman Sgt. Rod Grassman said the number of inmates who were either referred for or received intensive outpatient psychiatric services rose from approximately 128 in 2013 to almost 400 today. In that context, he said, the number of suicide attempts through August actually represents a “reduction.”

Grassman also said the sheriff’s office has added psychiatric personnel in the main jail and trained correctional staff to identify those at risk of suicide. He added that correctional deputies check single-occupant cells every 30 minutes and cells occupied by suicidal inmates every 15 minutes.

“People with mental health issues are particularly vulnerable to suicide and/or attempts,” he wrote.

Jails and prisons can be the worst place to address these issues, says a mental health expert.

“When you have someone with severe mental illness, they are not always able to comply in the ways that those institutions demand,” said Christine Montross, an associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University and author of Waiting for an Echo: The Madness of American Incarceration. “And if you don’t follow orders in jails and prisons, you incur greater punishment, so there’s a fundamental misalignment between these systems of control and security and these people who really need therapeutic environments rather than punitive ones.”

Between 2014 and 2019, at least eight people killed themselves in Sacramento’s jails, California Department of Justice records show.

The sheriff stopped informing the public about most jail deaths last year, when they reached a 14-year high.

At least one person died behind bars this year, though it’s unclear how. A sheriff’s spokesperson would only say that the Aug. 4 death of Travis Mitchell Welde, a 31-year-old Loomis man, was due to medical reasons and that the coroner was reviewing the circumstances. The sheriff’s office denied SN&R’s public records request for additional information.

As of Sept. 30, the county has confirmed 101 COVID-19 cases among the incarcerated population, a 68% increase in two months. Three cases were considered active.

The county identified 847 incarcerated people in the jails at high risk of becoming severely ill or dying if they were to contract the virus, according to court documents obtained by SN&R.

Emanuel, who was granted an early release due to being in the high-risk category, said that while those in the jail’s general population were tested for COVID-19, psychiatric patients held in solitary were not.

Politicians mostly silent

Rather than interrogate the loss of life behind bars, the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors rewarded Jones with a $12.3 million increase to his budget, most of which is intended to hire more jail guards.

Supervisors Phil Serna, Susan Peters and Don Nottoli declined or ignored SN&R’s requests to discuss jail conditions or the sheriff’s office.

Supervisor Sue Frost expressed support for the sheriff, while Supervisor Patrick Kennedy said he will propose the creation of a community review commission to work with the county Office of Inspector General and improve transparency within the sheriff’s office.

Fischer, the Disability Rights litigator who challenged the treatment of psychologically and physically vulnerable inmates, urged the county to step in rather than step back.

“This is an extraordinarily dangerous time for people incarcerated at the jail,” Fischer wrote in a statement. “They face enormous risks to their physical and their psychological well-being. This is a moment where the County must take deliberate steps to protect people at risk, and it is absolutely a moment to ask again, why are so many people, particularly people with mental health needs, being incarcerated?”

Emanuel, who turns 60 this year, pleaded for basic dignity.

“I don’t know what to say, but I do wish Sheriff Jones would change,” she told those watching. “I wish that they would treat these people with respect. I wish that somebody would look at this, because it is a problem. Funding Sacramento jail is not the answer.”

They can’t even use the phones or have visitors it’s not imprisonment it’s torture they lock em up by themselves for 14 days my friend just got out of there he had one shower in 14 days the nurses also try to pay the inmates to get vaccinations she told my friend she’d give him 20 bucks on his books it absolutely horror in there since covid