Sacramento’s sheriff logged the most jail deaths the same year he stopped telling the media about them

Sacramento’s jail system is supposed to be a way station for accused criminals navigating the court process or those serving local sentences of no more than a few years. For Christopher Stewart, it probably felt like a dungeon.

Stewart entered the jail on a warrant for driving under the influence in February 2018. According to a civil rights complaint filed in federal court, Stewart seriously injured himself in back-to-back motorcycle accidents in November 2017 and was using private insurance to treat multiple broken bones in his arms and legs when prosecutors had him booked into the main jail facility less than four months later.

Sacramento attorney Matthew Becker said the drab, mid-rise lockup located downtown didn’t provide his client with treatment or fresh bandages and refused to transport Stewart to scheduled medical appointments. He also alleged that Stewart was forced to sleep on an uncovered floor in the medical wing with an open knee wound and, when the time came to go to court, had his steel-plated wrist handcuffed to a wheelchair, causing the screws to loosen and bulge under his skin.

Becker said the jail’s “utterly horrific medical care” left his client “now basically permanently crippled” as a result. “That is willful deliberate indifference to serious medical needs and a major problem,” Becker told SN&R.

Stewart survived his experience in the jail. Many others haven’t.

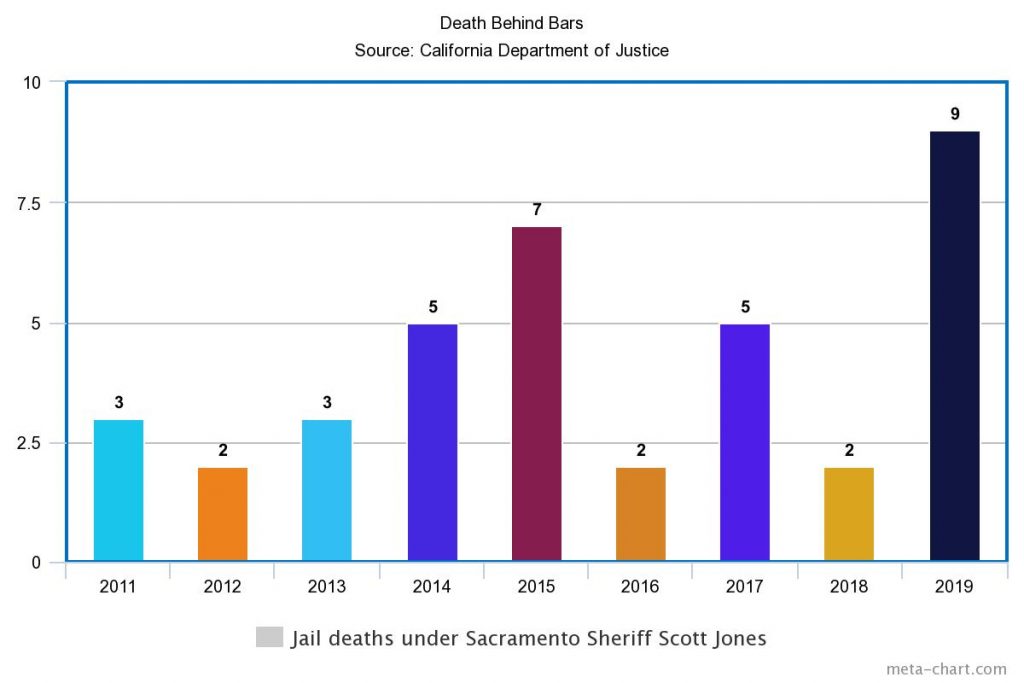

Jail deaths climbed to their highest number last year under Sheriff Scott Jones—a fact the three-term lawman largely withheld from the media.

Nine people died in Jones’ jails last year, California Department of Justice records show. That’s as many as the previous three years combined and the most under Jones’ watch since he took office in December 2010.

It’s also the largest body count behind bars since 2005, when 10 jail occupants died under the charge of then-Sheriff Lou Blanas.

The 2019 spike in jail deaths happened the same year that Jones’ administration stopped informing the media about them, raising fears that the sheriff may be hiding even more tragedies amid the pandemic. Unlike other California sheriffs, Jones refuses to provide data to the state about the number of COVID-19 infections and deaths in his jails.

“Transparency about these things is important,” said Aaron J. Fischer, an attorney for Disability Rights California.

In 2018, Disability Rights and the Prison Law Office successfully filed a class-action lawsuit that requires the sheriff’s office to drastically improve health-care conditions in its two jails. But, if anything, the downtown main jail and the Rio Cosumnes Correctional Center in Elk Grove have only grown more dangerous since a binding consent decree was brokered.

A hidden toll

All totaled, the 53-year-old Jones has lost more than 40 people in his jails over the past decade, according to state justice data and news accounts.

This includes the Aug. 4 death of Travis Welde, which the sheriff’s office acknowledged only after being contacted by a Sacramento Bee reporter, as well as an unknown number of people who suffered critical injuries inside the jail but died outside of it, which the sheriff isn’t always required to report to the state.

SN&R uncovered at least two such cases since June 2017, when inmate Clifton Harris, a 61-year-old cancer patient, was savagely beaten by a cellmate he’d previously warned jail officials about. Harris died when his family removed him from life support eight months later. The sheriff’s office didn’t report Harris’ death to the state because it filed court paperwork releasing him from its custody.

Nor did the department report the September 2018 death of 66-year-old Irma McLaughlin, injured an alleged fall from her jail bunk and who also died in a hospital bed after a legal released from custody.

Earlier this year, the Bee reported on the death of Antonio Lamar Davis, the victim of a jailhouse assault in December. It’s unclear whether the sheriff’s office will provide that information to state justice officials, as Davis died in a hospital 42 days after his attack.

Sheriff’s spokeswoman Sgt. Tess Deterding declined to say whether the department has reported all inmate deaths this year, but said in an email that basic information about in-custody deaths would be provided in response to public records requests.

The sheriff’s office, however, denied SN&R’s public records request for information about what happened to Welde, a 31-year-old Loomis man. Deterding later said correctional staff deemed Welde’s death a medical one.

Sacramento County had the third most jail deaths in the state last year, behind Los Angeles County with 86 jail deaths and under Sheriff Alex Villanueva and San Diego County, where 35 jail occupants died under Sheriff Bill Gore.

Riverside and Santa Clara counties both reported seven jail deaths to the state, while Alameda, Orange and San Bernardino counties reported six apiece.

Sacramento County has a smaller population than all seven of those counties.

A change in practice

It’s unclear when the sheriff’s office ceased its practice of issuing media releases whenever someone dies or is critically injured in its custody, but an SN&R review of archived press releases indicates most of last year’s jail deaths weren’t voluntarily divulged.

Deterding said there’s been no policy change, but acknowledged that the lack of releases isn’t in keeping with the department’s past practices. “It would be [a] normal course of action to release information on inmate deaths,” she told SN&R in an email.

Welde’s death isn’t the only critical incident this year that didn’t result in a timely press release from the sheriff’s office. The department waited 13 days to provide its account of a Sept. 5 incident in which four deputies shot and injured a 22-year-old Latino man suspected of vandalizing a fence and stealing a water hose from a Rancho Cordova apartment complex.

On Sept. 18, the department released a video summary that intercuts footage from two businesses and two patrol vehicles. It shows deputies pursuing the man, later identified as Miguel Hernandez, as he casually walks into a shopping center with an object in his hand that a caller identified as a fake gun. The department says its deputies fired at and missed Hernandez when he pointed the object at them, but that can’t be verified from the footage.

Deputies opened fire a second time and struck Hernandez when they say he pointed the object again. The department later determined the object was an ignition-timing device, which they claim was modified to resemble a gun.

The practice of shunning oversight isn’t unique to Sacramento’s sheriff, said state Assemblyman Kevin McCarty, a Sacramento Democrat.

“A classic Exhibit A is the Los Angeles sheriff,” McCarty said, referring to Villanueva’s frequent battles with that county’s Civilian Oversight Commission over the release of information concerning deputy shootings.

Some California sheriffs, McCarty said, “essentially stick up the middle finger” when asked to provide information to the public.

Sacramento’s political leadership has largely indulged the sheriff’s tight grip on the narrative.

The Sacramento County Board of Supervisors didn’t fight the sheriff when he unilaterally ousted an inspector general who took issue with a deadly 2017 shooting and and recently came under fire for allowing most of its federal pandemic aid to be spent on sheriff’s office salaries, rather than public health or economic development.

Supervisor Patrick Kennedy this month suggested redirecting $1.5 million from the sheriff’s budget to create a non-law enforcement response to mental health emergencies, but drew a mixed reception from his four colleagues.

Presumed innocent but booked to die

An exception to the sheriff’s information blackout on jail deaths came in January, when his department issued a release about an inmate homicide that occurred on Dec. 31 at Rio Cosumnes Correctional Center in Elk Grove.

Inmate Nikolas Kallergis was charged with beating a 62-year-old inmate to death in a shower area. Coroner records identified the victim as Richard Martin of Sacramento. Martin was serving a sentence at the custodial facility, but 22 of the 30 people who died behind bars since 2014 weren’t convicted of the crimes for which they stood accused.

Last year, five of the nine jail deaths occurred to people who were still under a legal presumption of innocence.

Some of the individuals who died were serving short sentences for minor crimes. Last August, Brian Debbs died from injuries the 33-year-old received during a July 8, 2019 fight with inmate Christian David Ento, the Bee reported. Debbs was more than a third of the way through a 120-day sentence for misdemeanor public intoxication and resisting arrest.

In June, Debbs’ family filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the county and its sheriff’s department.

The sheriff’s office has been a defendant or respondent in 399 federal lawsuits, an SN&R review of federal court filings shows.

The causes of jail deaths varied last year.

According to state justice records, a 25-year-old white man awaiting trial committed suicide, three people in the jail were beaten or strangled to death by other inmates, including a 61-year-old white man who hadn’t even been booked yet, two deaths were deemed to be of natural causes and three were still under investigation, including that of a 63-year-old Hispanic woman awaiting trial.

The Sacramento County District Attorney’s Office, which determines if crimes were committed, and the county Office of Inspector General, which considers whether policies were violated, have issued no opinions on last year’s jail deaths.

You might think the sheriff would be required to inform top county officials that he broke his own record for losing lives in his jails, which previously peaked at seven deaths in 2015, but not so. Jones’ department is only mandated to notify county Correctional Health Services and the coroner, a county spokesperson said.

That means elected supervisors, their chief executive and legal counsel can be kept in the dark about an issue that has cost Sacramento taxpayers tens of millions of dollars in courtroom settlements.

“It’s just a reminder that the consent decree that was reached was a piece of paper that still needs to be implemented,” Fischer said. “The consent decree wasn’t the end. It was the beginning.”

Becker, who also works as a criminal defense attorney, said a recent client was ordered to a 28-day quarantine in solitary confinement for coming into the jail with an autoimmune deficiency. Becker said his client spent a week in solitary until a judge ordered the client’s release.

“You have a pre-existing medical condition, they’re gonna lock you up for 28 days and not even let you make a court date?” Becker said. “Let me get the Constitution and see if I can find you a line that doesn’t violate.”

Be the first to comment on "The dungeon master"