Editor’s note: Did richer, white voters refuse to help Sacramento’s poor, black and brown kids?

The proponents of the March children’s funding ballot measure have just put out a post-mortem of why it failed, and it does not paint a very flattering portrait of Sacramento.

Their conclusion: Richer, white voters rejected a plan to mostly benefit poorer black and brown kids.

The report’s authors have a point of view, obviously. Still, the 18-page report makes a rather convincing case that the campaign “exposed the racial and economic fault lines of the city”—and that race and class largely determined the result.

While that may be disturbing for a city that takes pride in its diversity and unity, it shouldn’t be too surprising after the calls for economic justice following the police killing of Stephon Clark.

Some quick background: Measure G called for changing the city charter to direct 2.5% of unrestricted general fund revenues into a new fund for children and youth services. That would mean an estimated $10.1 million to $12.6 million a year on top of current spending for the next 12 years. Priority would go to help children and youth most impacted by poverty, violence and trauma, including LGBT, foster and homeless children.

More than 39,000 Sacramento voters signed petitions to put the measure on the ballot, but the City Council barely beat the deadline for the March primary. Supporters argued that these programs often get shortchanged because they don’t have the political clout of public safety unions, for instance. Opponents warned that the measure could force cuts to basic services in a budget crisis. (SN&R recommended a “no” vote, in part because there was no escape clause in case of a deep recession.)

In the March 3 primary, Measure G was soundly defeated, with 54% against.

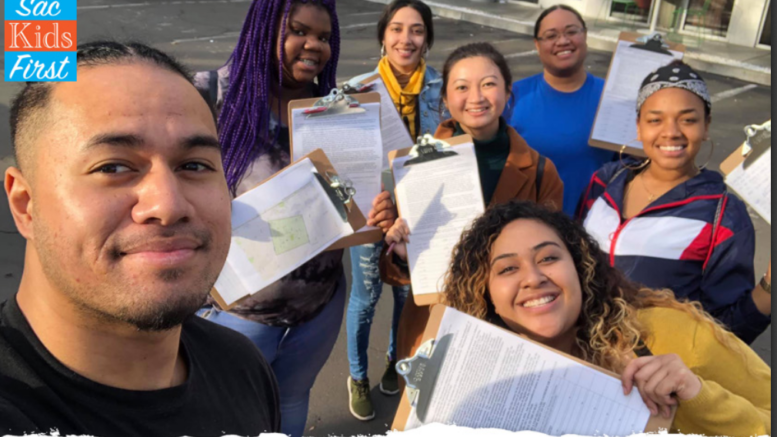

The report—entitled “A Tale of Two Cities: The Campaign for a Sacramento Children’s Fund” and produced by the Sac Kids First coalition, the measure’s sponsor—takes a deeper look at what happened.

An analysis of the voting shows that, in general, neighborhoods with a larger white population and a lower poverty rate opposed the measure. They include East Sacramento, Land Park, North Natomas and the Pocket. By contrast, neighborhoods with more people of color and higher poverty rates voted “yes.” They include Del Paso Heights, Fruitridge, Meadowview and Oak Park.

“Given that voters in both types of neighborhoods largely received the same information about Measure G, we can see how these voters, who live literally down the road from one another, bring very different perspectives to priorities for the city of Sacramento,” the report says. “People of color in Sacramento have experienced historic and current day discrimination, oppression and disinvestment. The difference in experience between voters of color and white voters influences how these groups of voters view policy issues such as those represented by Measure G.”

The study also points out that Sacramento’s power structure mostly lined up against the measure. The opposition campaign was mostly funded by the influential fire and police unions, as well as developers and business interests. The pro campaign was financed by members of the Sac Kids First coalition, including groups that could have received grants from the measure.

Also, the measure’s opponents on the City Council (Angelique Ashby and Jeff Harris) represent more affluent districts, while its supporters (Eric Guerra, Jay Schenirer and Allen Warren) represent districts with more people of color and higher poverty. The measure was also backed by three challengers who are people of color: Katie Valenzuela, who unseated Steve Hansen in District 4, and Les Simmons and Mai Vang, who are in a November runoff in District 8.

Mayor Darrell Steinberg weighed in against the measure in a late move that may have swayed some undecided voters.

Just as ballots arrived in the mail, he offered what he called a less risky alternative that the council endorsed on Feb. 25: A ballot measure in November to set aside 20% of new revenue growth—about $2.5 million to $3 million a year—for children’s programs. The backers of Measure G are still hoping to amend Steinberg’s measure to prioritize programs that close racial gaps for children.

“People of color in Sacramento have experienced historic and current day discrimination, oppression and disinvestment. The difference in experience between voters of color and white voters influences how these groups of voters view policy issues such as those represented by Measure G.”

Finally, the report argues that some voters may have been scared by growing awareness of the COVID-19 pandemic, which closed Sacramento schools and businesses two weeks after the election.

Across California, the success rate for local tax measures was significantly lower in March than in recent primaries. Voters approved 23 of 34 majority-vote city tax measures, like Measure G. That 68% passage rate compares to 94% for similar measures in June primaries between 2010 and 2018, according to a count by California City Finance.

The study points out that in Sacramento two other children’s funding measures also failed recently: a June 2016 city proposal to increase taxes on marijuana business, and a November 2016 Sacramento City Unified parcel tax for at-risk youth and enrichment programs.

All three efforts, the report says, were aimed at helping poor children of color who often attend public schools with fewer resources, then have less access to after-school and summer enrichment programs.

“From the election outcomes, it’s clear that there has yet to be an effort large enough, and united enough, to win,” the report says.

Now, the pandemic means more uncertainty for the city’s funding of children’s programs and for the prospects of the November measure.

“What is clear is that regardless of how long the pandemic lasts, the tale of two cities will continue,” the report says. “The families and children in the neighborhoods that supported Measure G are bearing the brunt of the pandemic-induced downturn and will likely be affected over the long-term by the crisis.”

I had a “Yes on G” sign but tore it down when I heard about that $6000 dinner at Ellas by Daryl Roberts, a “person of color”, a phrase over used in this article. Very disingenuous of this report not to mention this outrageous conduct.

Sadly, Karen Solberg, that is typical of the race-baiters at the Soviet News and Review.