Sacramento County’s aging jail system ordered to release more than 400 inmates over coronavirus concerns

Gloria Abernathy was panicking that something bad had happened to her daughter in jail—and she wasn’t even thinking about the coronavirus.

“I’m so afraid for her,” Abernathy told SN&R. “They won’t let me see her.”

Abernathy’s daughter was arrested in North Highlands early the morning of March 12, one week after Sacramento County declared a public health emergency and two days after the county’s first COVID-19-related death.

So much has happened in the blurry weeks since that it’s difficult to keep track.

On Wednesday, March 25, the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office announced that it was under a court order to release 421 inmates with less than 60 days on their sentences “in the best interest of public health.”

Eligible inmates can’t be serving time for domestic violence, driving under the influence or offenses that would require registration as a sex offender.

The order was hammered out by the offices of the district attorney and public defender, signed by Sacramento Superior Court Judge Michael G. Bowman and directs the Sheriff’s Office to make the releases by Monday, March 30.

But the jail population was already shrinking in the weeks leading up to the judicial directive. The question is whether these efforts will be enough to stave off an outbreak inside two aging facilities without adequate medical services and a population prone to other ailments.

A sharp drop in jail bookings

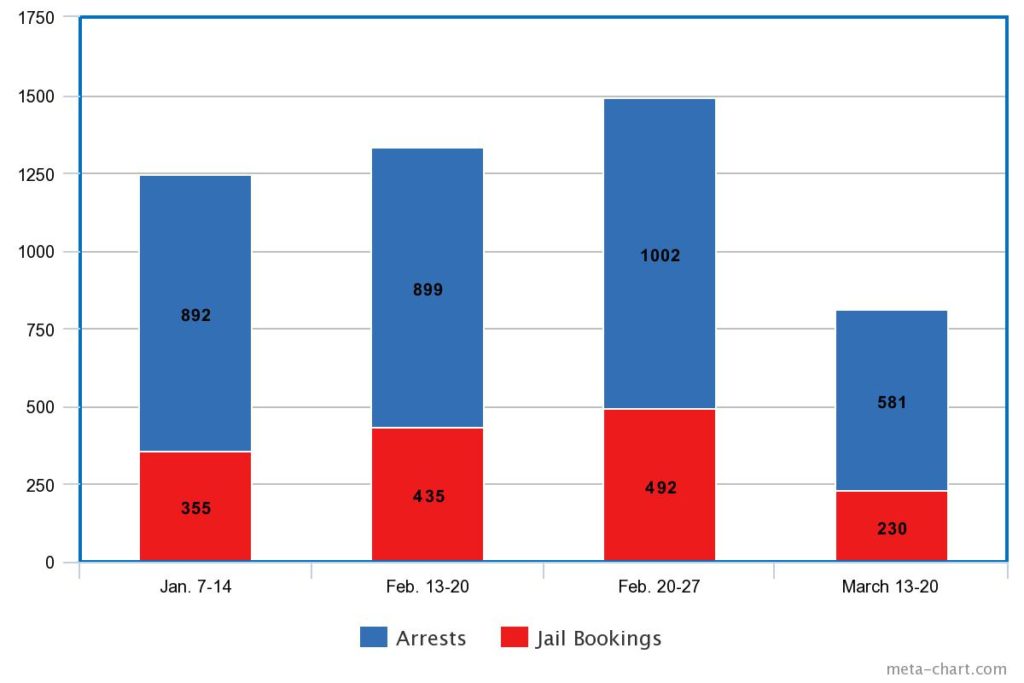

According to an SN&R analysis, weekly jail bookings have been nearly halved compared to where they were before the outbreak.

In the week ending March 20, the jail system accepted 230 new inmates, the vast majority of them men and at the downtown jail, not the Rio Cosumnes Correctional Center near Elk Grove. Weekly incarcerations were down 47.1% from the month before, when 435 people were booked into Sacramento County’s two jails from Feb. 13-20.

The incarceration rate for new arrests also dropped, with only 39.6% of the people arrested in the week ending March 20 spending any significant time in jail, compared to 48.4% a month earlier.

Citrus Heights police Chief Ron Lawrence said the Sheriff’s Office implemented some new restrictions about who could be booked into jail to limit the chances of viral exposure. Lawrence said that if arresting officers had reason to believe that anyone arrested for a misdemeanor was infected with COVID-19, they should release them with a citation to appear in court rather than take them to the downtown jail.

“That’s not to say we’re not out there enforcing the law,” Lawrence said.

As of Friday morning, there were 164 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Sacramento County—a 31% increase in just two days. Six people have died of complications from the virus, all of whom were 65 or older, or had underlying health conditions.

The county would not say whether any jail inmates have tested positive for COVID-19, citing, in part, the high number of requests for testing data.

“Getting this information is not immediately accessible so to manage the resources that we have efficiently, Sacramento County Public Health will not release information on testing data,” county spokeswoman Brenda Bongiorno wrote in an email. “However, Sacramento County Public Health prioritizes those who are incarcerated/jail/prison for testing because they are congregate settings. Those who show symptoms or exposure would be isolated and triaged for testing.”

But there are signs that the virus has reached the vulnerable jail population, most of whom have not been convicted and are more likely to having the underlying health conditions that put them at greater risk of contracting the respiratory illness.

In a letter to county and jail officials, attorneys with Disability Rights California and the Prison Law Office, which secured a major settlement regarding inhumane conditions at the jail, especially for prisoners with mental health issues, said they knew of “multiple” inmates who have been placed in solitary confinement because they may have been exposed to COVID-19.

The letter encouraged the county to instead draw down the jail population, including through pretrial and work releases.

“The Jail’s crowded, confined, and limited-ventilation facilities create a grave risk of COVID-19 transmission to a Jail population with high risk factors,” the attorneys wrote on March 18. “The Jail also lacks adequate facilities to quarantine or medically isolate people who have symptoms of COVID-19 or report recent exposure to the virus. We are aware of multiple people in custody at the Sacramento County Jail in recent days who have been subject to ‘Total Separation’ in non-medical isolation units based on possible COVID-19 exposure.”

Total separation is what the jails call solitary confinement.

The ACLU has called on sheriffs across the country to reduce jail populations by releasing convicted inmates with less than 30 days left in their sentences, as well as older, sicker individuals who are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, “unless there is clear evidence that release would present an unreasonable risk to the physical safety of the community.”

The California State Sheriffs’ Association declined an interview request.

Worried about her daughter

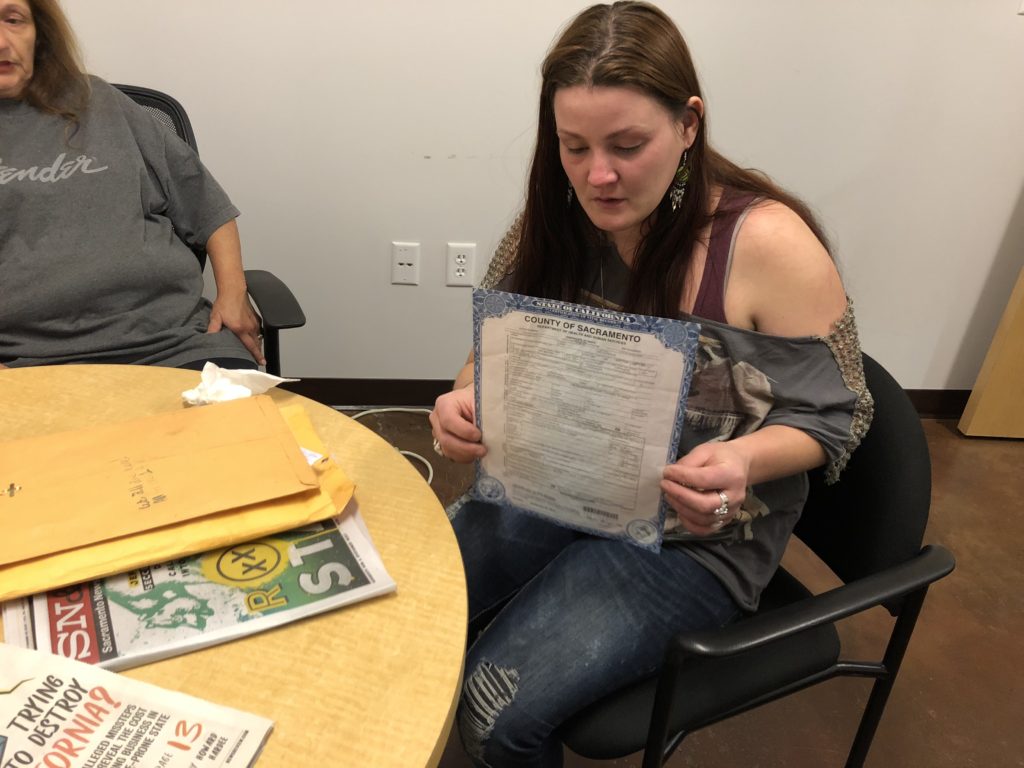

Abernathy says her daughter Desiree, 32, who is in and out of homelessness, was standing in front of a business at Roseville Road and Oakhollow Drive because it was well-lit and safer in the predawn dark. According to booking logs, sheriff’s deputies picked her up for trespassing.

Either way, deputies discovered that Desiree had outstanding misdemeanor warrants and booked her into the downtown jail.

When Abernathy visited her daughter the next day, on March 13, she says she found an extremely agitated young woman on the other side of the bleary, inches-thick glass.

“She said, ‘Mom, you have to get me out of here. I can’t do it in here,’” Abernathy recalled, her own voice shaking. She continued in her daughter’s voice. “‘I’m gonna tell ’em I’m gonna commit suicide. I can’t do it.’”

Abernathy says she urged her daughter not to do that, but learned at the March 16 arraignment she was under psychiatric evaluation.

Abernathy feared the worst. Her friend’s mother died from a head injury sustained in the jail in September 2018, and Abernathy says she witnessed mistreatment and heard screaming from women placed in isolation when she was a jail trustee, an inmate whose good behavior is rewarded with perks.

“I know what they do in there,” she said. “I’m just freaking out.”

Still, Abernathy couldn’t afford her daughter’s $41,000 bail, even at the 10% rate a bail bond agent would charge. Plus, Abernathy knew her daughter had missed her court dates before—that’s why she was in this mess—and didn’t want to risk Desiree skipping out on bail and costing her four grand.

Abernathy says she was also just trying to show her daughter—who lost her biological father to a heroin overdose and has struggled with methamphetamine and alcohol addiction—that there were consequences for her actions.

“But I didn’t expect this to happen. I didn’t expect this,” Abernathy said.

A day later, her worst fears were quelled. Desiree did make it to court, where every other seat was left empty for social distancing. A judge ordered her release.

“The DA didn’t want to let her go because she had too many ‘failure to appears,’ which is understandable,” Abernathy said.

The jail processed Desiree’s release around 1 a.m. One of the women she got out with still had a charged cellphone, which is how Desiree was able to call her mother and ask for a ride.

“They let three girls out in the middle of the night; can you believe that?” Abernathy said.

The Sacramento County grand jury criticized the Sheriff’s Office’s widespread practice of late-night jail releases in 2018 and urged it to change course. The Sheriff’s Office disagreed.

Abernathy picked up her daughter and the two other women. It was late, so Abernathy didn’t get their full story, but says it didn’t sound like anything bad happened to them. Desiree said she was moved to the psych ward after complaining about a cellmate and ended up speaking to a male psychologist. She wasn’t roughed up, Abernathy said.

“One of the girls my daughter came out with said they’re releasing a bunch of people because of the virus,” Abernathy said on March 18—one week before the court ordered even more to be let out.

I cannot understand why releasing 400 convicted adults can possibly help anyone?

If anyone can explain, I am willing to listen.

Thank You