By Scott Thomas Anderson

Sometimes the words that are never spoken during a big political moment reveal more than the ones that are.

On Jan. 28, elected officials, business leaders and nonprofit groups gathered at City Hall for a major announcement. Mayor Darrell Steinberg was ready to deliver on a promise he’d made while relentlessly campaigning for the Measure U half-cent sales tax increase approved by voters in November 2018. Working with City Councilman Steve Hansen, Steinberg unveiled a plan to use bonds financed with some Measure U revenues to put roughly $100 million into the new Sacramento Affordable Housing Trust Fund, which in turn will help affordable housing developers.

With luck, the mayor added, the fund can be “catalyzed” to nearly $200 million, putting Sacramento in better position to leverage state and federal grants and private sector investment—and spur a new wave of affordable housing projects in the city.

Groups including the Sacramento Housing Alliance and Mutual Housing California praised the mayor for his idea. So did other council members.

But there was an elephant in the room—and virtually everyone seemed to avoid stepping on its tail: The city of Sacramento already has an affordable housing trust fund. That’s literally what it’s called, the city’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund. It’s existed for 31 years—and it’s supposed to be funded by developers who are making money by building all the shiny, pricey condos and apartments across Sacramento.

While no one was interested in discussing the original housing trust fund that night, almost every council member present, with the exception of the mayor, had plenty to say about it four-and-a-half years ago. That’s when the council decided to stake the bulk of the city’s affordable housing future on that fund by allowing developers out of their obligation to build low-income units.

Before then, the city compelled developers to build 15% of any residential project as affordable units before moving ahead.

But in September 2015, Hansen, Angelique Ashby, Larry Carr, Eric Guerra, Jeff Harris, Rick Jennings, Jay Schenirer and Allen Warren all voted for the policy shift. Instead of requiring developers to build units for low-income families, they could opt out by paying a fire sale-priced fee against every square-foot unit of their project. The money would then go into the affordable housing trust fund.

Housing advocates, poverty experts and nonprofits representing the disabled all warned council members not to do it. They did it anyway.

With most developers in Sacramento free to focus on creating market-rate and high-income housing, the Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency was tasked with finding the few builders specializing in affordable projects and helping them break ground with money from the trust fund. In 2017, with Sacramento experiencing one the highest year-to-year rent increases in the nation, SHRA and the trust fund had contributed to building exactly zero affordable units in the city.

According to SHRA’s latest report in 2019, its trust fund has since only helped build 159 affordable units in the city, at a time when the city and county need an estimated 63,000 combined to address the local housing crisis. Worse yet, a recent analysis by the mayor’s office found that between October 2013 and Dec. 31, 2018, the city only issued building permits for two units of extremely low-income housing from any source, and only 208 permits for units priced for very low-income renters.

Environmental policy director Katie Valenzuela, who is trying unseat Hansen on March 3 to represent the central city, says the costs of the 2015 decision are now undeniable.

“What they did was a mistake,” Valenzuela said. “And we can spend as much public money as we can, but it’s never going to make up for the fact that developers aren’t paying their share for the impact on the community.”

Hansen said he still supports the inclusionary housing requirement in new growth areas, and explained his 2015 vote by saying that the city was trying to get more infill housing and city staff and outside analysts concluded that “overly burdensome fees” would get in the way.

“We should annually revisit these fees to ensure that they are appropriate and that our goals for infill and affordable housing are balanced,” he said in a statement. “Sacramento’s costs for labor and construction materials are still tied to the Bay Area costs, which means that we still see many projects struggling to get built.”

Shadow of a recent past

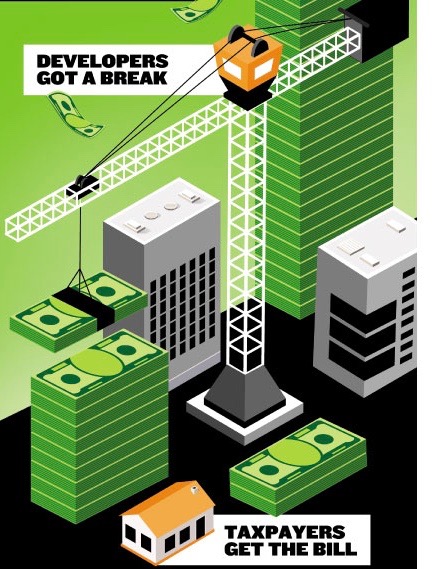

Steinberg was elected in June 2016 after the decision to eliminate the inclusionary housing requirement was made, and he’s been trying to deal with the fallout ever since. The nonprofits who build affordable housing may all agree his new trust fund is a good idea, and badly needed, but some housing advocates also view it as way of making taxpayers assume the burden for developers who are still passing directly to Go on the Monopoly board.

The road to this developer-dominated situation began Sept. 1, 2015, when the council, led by then-Mayor Kevin Johnson, voted to change Sacramento’s housing strategy. The city’s community development department had been considering the move since 2013, when aftershocks from the Great Recession were causing stagnation in the building market. But by the time the proposal came to the council, the economy had experienced five straight years of economic growth. Nevertheless, city staff still wanted to put developers in the driver’s seat to spur construction.

Associate planner Greg Sandlund told the council that while the inclusionary rules accounted for 25% of all affordable housing built in the city since the year 2000—some 1,559 units—his team believed alternative programs were more effective.

Sandlund described the 15% mandate as a “well-intentioned” program that could make housing too expensive for developers. Instead, his department recommended switching over to a flat, per-square-foot fee, which developers would pay into the SHRA-administered affordable housing trust fund.

“This approach gives the city the flexibility to look at these large projects on a case-by-case basis while incentivizing the development of affordable housing,” Sandlund said. The new strategy, he said, would create “a context-sensitive ordinance” that could “withstand the cyclical nature of the housing market.”

The Sacramento Housing Alliance did the math and determined that developers would need to pay between $9 and $12 per square foot to keep up with the pace of units built under the inclusionary rules. The city’s development department, however, decided to make that fee $2.58 per square foot—and that’s what the council agreed to.

Seeing the writing on the wall, then-SHA director Darryl Rutherford called it “a sad day for Sacramento.” Representatives from Mutual Housing California, Sacramento Area Congregations Together, the Sacramento Women’s Council and Resources for Independent Living all told the council that the fee was way too low, or that eliminating inclusionary housing was a disaster waiting to happen.

Yet a number of developers and downtown business representatives also showed up that night to assure council members that abandoning the inclusionary housing requirement was the right decision. And their advice was ultimately followed.

Asked last week if the council had made the wrong call back in 2015, Steinberg was reluctant to criticize his colleagues.

“I don’t want to second-guess the decisions of public servants who were trying their best,” he told SN&R. “And there was a rationale behind what they did.”

But at least two challengers in the March election are openly criticizing that decision made by their opponents.

Twin Rivers Unified School District trustee Ramona Landeros is running against District 2 Councilman Allen Warren and says that his vote to eliminate inclusionary housing damaged north Sacramento. Landeros, who grew up with a disabled brother, is particularly concerned that several nonprofits that house residents with disabilities are struggling more than ever to keep their clients from being priced out of their apartments.

“When we’re talking about Social Security, that does not even pay for housing anymore,” Landeros said. “And so we’re seeing more and more people with disabilities living on the streets. That’s just wrong. It’s criminal in this country where we have so many resources.”

From Valenzuela’s perspective, the 2015 housing decision fits in with a broader pattern of the City Council listening to large campaign donors and special interest groups over community groups and the advice of other experts.

“They continue to really embrace this theory of trickle-down economics, which hasn’t been working on a lot of fronts,” Valenzuela said.

While Steinberg may not want to undermine the council members he works with, he fully admits that he’s a mayor with a housing crisis on his hands. He says that’s one reason he campaigned so hard for the Measure U tax increase in 2018 and then set his sights on the new affordable housing trust fund.

Asked how he plans to help the public differentiate between this new housing trust fund and the original one, Steinberg’s answer was simple: “Well, the SHRA fund doesn’t have any capital.”

The mayor has also been clear that the new trust fund will be administered directly by the city rather than SHRA, which has traditionally handled building affordable units for both the city and the county.

Asked why City Hall wants total control over the new funds, Steinberg said he wants a multifaceted approach to tackle the housing insecurity that so many are experiencing.

“I’m determined to make it clear that the city has skin in the game,” he told SN&R. “It demonstrates that the city, as an entity, is not just contracting this problem out or outsourcing it to the housing authority. … How we’ll define roles and responsibilities, we’re still working on that.”

Dealing in the present

When Steinberg unveiled his plan Jan. 28, the detail that housing advocates praised the most was its spending priorities. The mayor intends for 80% of the new trust fund to be geared toward building low-income and extremely low-income housing, with 40% earmarked for the latter. The Sacramento Housing Alliance has released several reports since 2017 showing that those two categories constitute, by far, the city’s greatest housing need.

“That is the segment of the population who the market does not reach,” said Cathy Creswell, the alliance’s board chairperson.

The new fund is also designed to encourage innovative, nontraditional housing models that involve smaller, cheaper units, which are also faster to build. That could even include projects with tiny homes, pallet homes and refurbished shipping containers, the mayor explained.

Steinberg said it often costs roughly $300,000 of public subsidy for every unit of affordable housing. Those units also tend to have a lengthy permitting process. The mayor said that the new fund can likely bring a lot more units online, and do it a lot sooner, if builders are thinking outside the box. Steinberg is proposing that 30% of all affordable housing that the city helps finance should cost less than $100,000 per unit in public money.

Hansen, who played a significant role in creating the new trust fund, is also optimistic. He called the strategy an absolute necessity.

“There are tens of thousands of families in our region—and especially here in our city—that want relief from increasing rents, that want stability, that want to know that they won’t have to pay more than a third of their income on rent, which is the classic threshold for whether it’s a burden or not,” Hansen said during the announcement.

The next step in creating the new trust fund is for the city treasurer to conduct a “stress test” to make sure the general fund is healthy enough to handle the added debt from the bonds.

While some housing advocates are encouraged by these developments, others insist the city needs to focus on corrective action around inclusionary housing. Steinberg told SN&R that while he supports the state developing better affordable housing standards across the board, he doesn’t envision the council revisiting its 2015 decision any time soon.

Nicholas Fish, who is with the Sacramento Tenants Union and has studied urban planning for years, says the council’s stance on inclusionary housing is not just absolving developers of their responsibilities, but is keeping the city segregated by income levels.

“Getting rid of those standards seems really out of touch with working people,” Fish said. “If you study how inclusionary housing has worked in a lot of places, you see it generally prevents creating clusters of only one income group in one area, so you’re not just leaving certain neighborhoods as pockets of poverty.”

Fish also views the new housing trust fund as a “taxpayer-leveraged solution” for what should be a market-based strategy that leverages developers who want to build in Sacramento.

The debate over the new affordable housing fund is playing out at the same time as the ongoing fight over rent control in Sacramento. Last August, the mayor led the council in passing the Tenant Protection and Relief Act, which caps annual rent hikes at 10% and bans no-cause evictions in the city for the next five years.

But housing advocates are still pushing for a stronger, permanent measure after collecting 47,000 signatures to qualify it for the ballot. The council refused to place it before voters on March 3, and hasn’t acted to put it on the Nov. 3 ballot, either.

Valenzuela, who’s made the plight of tenants and low-income families a major platform in her campaign, says the conversations she’s had with voters reveal that many Sacramentans aren’t aware the city ditched its inclusionary housing rules.

“A lot of people don’t really know,” she said. “It’s because they did it before the crisis became so acute.”

Be the first to comment on "Who’s paying to fix Sacramento’s housing crisis? How developers got a break while taxpayers got the bill"