Artist Tavarus Blackmon explores themes of police brutality, animal cruelty and gender and racial inequities, while fighting for a better future

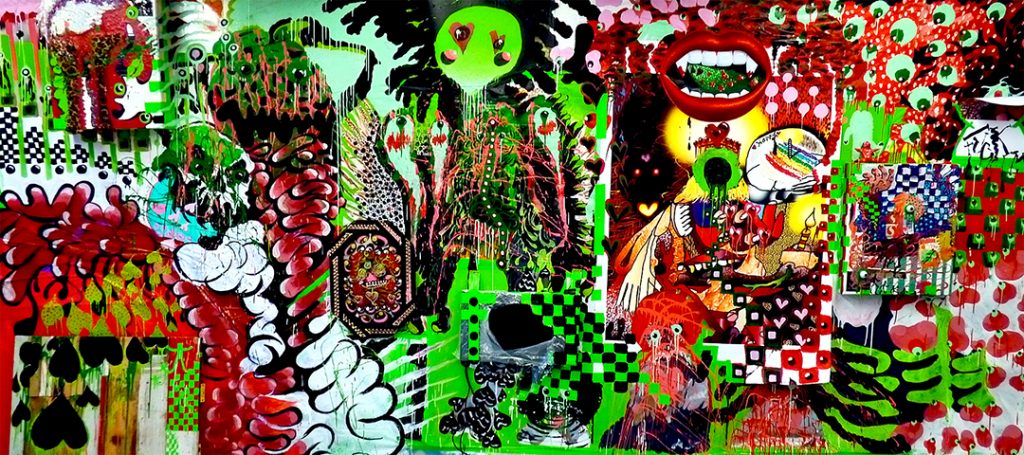

A pair of red lips part to reveal a set of fanged bloody teeth. In place of a tongue is a green shape inlaid with angular red shapes. The mouth doesn’t extend to a face; instead, surrounding the recognizable form is a sea of garish abstractions: a cartoonish candle, hearts, stick figures, eyeballs, checkerboard and polka dot patterns, gingerbread men and monsters.

On the surface, “Autocombustophobia” has the aesthetic of a playful abstract work of art. However, a deeper look reveals the darkness that is embedded in the work.

“A lot of people relate to play, relate to fun, relate to what is good in our culture, and I want to be part of what is good in our culture, but it’s important for me to talk about is difficult too,” said artist Tavarus Blackmon. “If I can marry the two, then maybe I can change the way people think.”

The local artist with a master’s degree in fine arts from UC Davis has had to juggle a lot in his mind in recent days, including the nationwide protests over the police killing of George Floyd and the online gallery, Art Music Lit Space, that he is curating in response to COVID-19.

“I guess I’ve been feeling a little depressed here and there,” he said. “I’m in between being a business owner, being a concerned citizen and figuring out all that stuff at the same time, and then sharing my voice and my response to the injustice in our society.”

Whether in a painting or music or video, Blackmon’s art revolves around a variety of themes, including police violence. In his painting “Masters Game,” he depicts a figure in a black cowl—reminding the viewer of Philip Guston’s paintings of the Ku Klux Klan— towering menacingly over a frowning gingerbread man behind bars.

“People have been making paintings about police brutality long before me, and we’re still having the same conversation.”

“I want my work with the gingerbread man— which is all about Black disenfranchisement and police brutality— to have an effect on our culture,” he said. “George Floyd was just killed. People have been making paintings about police brutality long before me, and we’re still having the same conversation.”

While his work is full of ideas formed by the juxtaposition of object and form, Blackmon avoids assigning specific meaning. Instead, he says simply he wants his work to be transformative.

“The interesting thing about art is that everyone is going to feel something different about it or think something different about it. I make art because I’m an artist and making art is what I do,” he said. “I want people to be transformed by the act of having been present with the work, ’cause that’s what happens to me when I make it.”

Blackmon uses an automatic drawing process in his work, where each line is dictated by the painting, allowing for art-making centered on the act of discovery.

“The easiest way to describe it is like seeing lines where there are no lines,” he said. “I don’t tell myself, ‘I’m going to make a circle’ or ‘I’m going to make a zig zag line.’ The shapes and the marks kind of appear before I make them, and I just follow them with a mark-making tool.”

Blackmon’s years of experience and study help to guide his decisions, including when to stop.

“When it comes down to it, there’s no end to the marks that you can make,” he said. “There has to come a point in the work where the work has to stand on what it is up to that point. Otherwise it’s madness.”

Blackmon constructed the 17-foot-wide Autocombustophobia in 2017 during his time at UC Davis, using plastic, glass, tin, a television monitor and plenty of duct tape. The mixed-media piece employs graphic lines and vibrant colors that send the viewer’s eyes ping-ponging across the cartoonish canvas.

“I think people can escape in the work that I make, but they can escape to ideas outside of their own, or escape to a way of thinking that has to do with core values of humanity and justice,” he said.

In “The Politics of the Cartoon and Contemporary Art,” he says: “With a crooked line and a high key color I create original forms and unrecognizable spaces…. That is to say the aesthetics of the cartoon hover the grotesque like a fly over a dying body and throughout history have been a means to think critically about difficult subjects.”

“[Cartoons] don’t activate your brain in the same way watching Tom Brady throw a touchdown does. A lot of people feel like a hero when Tom Brady throws a touchdown. I think a lot of people feel like they got killed when George Floyd was murdered,” he said.

Although his work deals in cartoonish imagery, Blackmon refuses to hide from brutal truths.

“I want that for my children, but they’re young. They can live in a fantasy world and play make believe and pretend,” he said. “I’m an adult. I’ve seen people get killed in the streets, injustices that we’ve been dealing with forever, farm factories killing animals by the millions, women treated as second-class citizens.”

Blackmon’s hope is that real change will come from the ideals that he fights for in his work.

“Hopefully, we’ll have larger overarching changes in our culture that reflect, what are the American ideals,” he said. “It’d be nice to not live in some ironic kind of state of being where we say America is one thing, but it’s actually another. It’d be nice if America actually was what it says it is, you know?”

Be the first to comment on "Heart to Art with Tavarus Blackmon"