Editor’s note: Will Sacramento give its blessing to a “Black Lives Matter” sign in a city park?

“Black Lives Matter”—the phrase as well as the organization—became a point of political controversy during the thousands of anti-police violence protests last year.

Last weekend, a Norwegian member of parliament reported receiving threats after nominating the Black Lives Matter movement for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Now, a proposed BLM sign is bringing the issue to City Hall.

On Thursday evening, the city’s Parks & Community Enrichment Commission debated a request to allow the sign to be erected at McClatchy Park. The commission voted 9-0 to recommend approval to the City Council and also directed the artist to invite local Black Lives Matter leaders to be part of the presentation to the council.

Thursday afternoon, Mayor Darrell Steinberg tweeted his support: “I wholeheartedly support installing this sign in McClatchy Park, where it can serve as both a community affirmation and an ongoing challenge to all of us in @TheCityofSac.”

Here’s the back story: Last summer, woodworker Zach Trowbridge created a sign by cutting and painting large letters spelling out “Black Lives Matter.” On the letters, he wrote the names of people killed by police.

According to the staff report, he donated the sign to a local group that put it up in Curtis Park, without the city’s permission, last June. The group also added a blank board where people could write their own messages. Residents also added smaller signs and candles to the site.

It became a neighborhood gathering spot for people to express outrage and sorrow after the police killing of George Floyd. But after about a month the sign was vandalized and Trowbridge took it down.

“The entire sign was knocked down and the large BLM letters were broken into pieces,” reported the Sierra Curtis Neighborhood Association. “Neighbors tried fixing it, but ultimately the broken pieces were too compromised for the sign to remain standing.”

Other “Black Lives Matter” signs and murals across the nation were also damaged and defaced.

Trowbridge painstakingly repaired his sign, then after hearing from residents, he talked to the Oak Park Neighborhood Association and District 5 Councilman Jay Schenirer about a new location.

“Many have voiced that they think McClatchy Park would be an excellent long term home for the sign given it’s [a] historically Black community and not being far from the old Black Panther Party HQ on 35th Ave.,” Trowbridge wrote in a memo to the city.

The neighborhood association says it’s “proud to support” the sign.

“This installation is consistent with our objectives to promote a safe and inclusionary environment for all residents,” it wrote to the city. “As tension has grown throughout the nation, it is more important than ever to unequivocally denounce white supremacy and support the safety and security of all community members.”

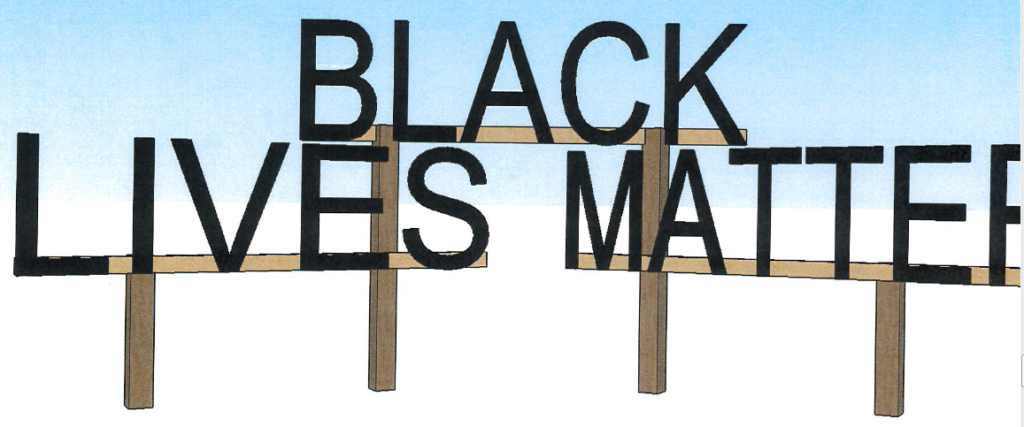

Trowbridge says the proposed sign is sturdier, in one piece instead of three like the one in Curtis Park, and with four posts cemented into the ground. “I would also make it sort of a living [altar] that has an area where people could write messages,” he wrote. He says he would maintain it during the six-month agreement with the city, which could be extended.

Thursday night, Trowbridge, 28, an IT manager and vice president of the Hagginwood Community Association, told the parks commission that he was spurred to create the artwork after the killing of George Floyd and that given the history of police violence, there’s a moral obligation for the city to adopt the sign as “government speech.”

“History has its eyes on you,” he said.

Tanya Faison, founder of Black Lives Matter Sacramento, called into the meeting to support the sign, but said she wants to make sure it includes the names of two men killed by local law enforcement in January.

She and others, however, also said she wished a Black artist had the opportunity to offer such a sign. Trowbridge replied that he made the sign on his own without compensation and that he agrees a Black artist should be commissioned.

Also, parks commissioner David Guerrero pressed Trowbridge on how active he had been in Black Lives Matter and faulted Trowbridge for not talking to local Black Lives Matter leaders in advance.

Trowbridge conceded that he wasn’t a direct activist and that while he talked to people involved in the police reform protests, he “dropped the ball” in not contacting BLM leaders.

At Guerrero’s urging, the parks commission also passed a motion calling for the active involvement of local BLM officials. It was a 6-3 vote, with some commissioners saying that it was unnecessary and that Trowbridge hadn’t purposely ignored the local BLM chapter.

There’s also more than one catch at City Hall.

The city has a procedure to temporarily put artwork on city property, but staff decided that the sign didn’t qualify as art.

Because the sign’s purpose is to express an opinion, the City Council would need to approve its placement as “government speech,” the staff report says.

And the staff recommendation is that the installation cannot include a message board or an area for other memorials because that would create a public forum—a “free speech” area where anyone could put up their own signs with political statements.

“Once a public forum is created, the City is limited [in] its ability to remove signs erected by others no matter how offensive the pictures or message might be and no matter if the unauthorized signs make a statement about a different subject matter,” the staff report says.

If approved, the sign would be in the park for a limited amount of time and the city could remove it if it’s vandalized again, isn’t maintained or becomes a safety hazard.

If the sign isn’t approved, the staff report mentions that the city could instead paint “Black Lives Matter” on the park’s basketball court or add metal letters to the park’s gateway arch.

Be the first to comment on "Sign of the times"