Amazon’s Ring may have helped catch a killer. What else does it catch?

Homicide detectives Christopher Britton and Courtney Bartilson arrived at the short, gabled home in the Bowling Green neighborhood of Sacramento County around 2 a.m. on April 14, 2019, a Sunday.

Britton found the residence tiled in broken glass and heavily spattered in dark, dry stains. He followed the sound of running water to the master bedroom. The victim, identified as Damien Gregory Michael, age 49, lay on his back. Britton didn’t know the man but wouldn’t have recognized him if he did. Michael’s face had been driven in by a heavy object wielded with unrelenting force.

“The condition of the house was in disarray, especially in the master bedroom,” Britton recalled during a video-conferenced preliminary hearing this September in Sacramento Superior Court.

“Blood was everywhere,” testified Britton, now a sheriff’s sergeant at the Rio Cosumnes Correctional Center. “The decedent had been dead for at least a couple of days, in my opinion.”

The killer was long gone, so Britton went looking for the killer’s instrument. Someone had plopped a laptop and electrical fan in the master bathroom’s tub and turned on the faucets. Britton moved to the guest bathroom where a kettle bell was getting doused in the sink. The fifth-year detective’s walk-through had turned up a possible murder weapon. He only had to backtrack to the front door to locate a potential eyewitness.

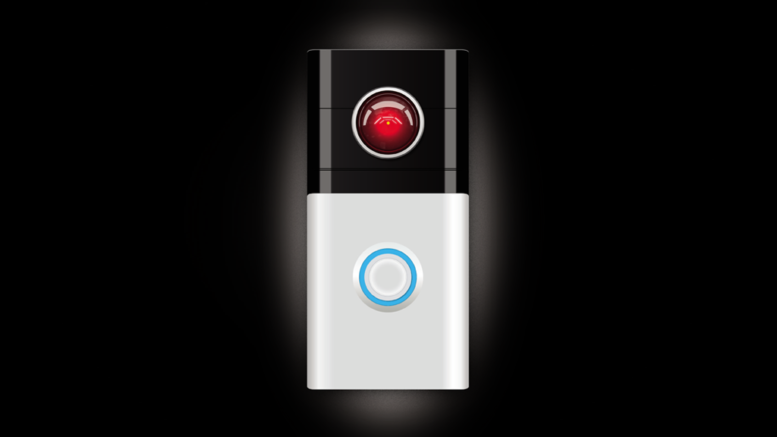

Fixed to the outer wall was a plastic, two-toned console with a pinpoint orb staring straight ahead. It was a Ring video doorbell, an increasingly popular home security gadget that turns the front of the house into an endless stakeout. Detectives hoped the device had seen the killer.

Privacy advocates warn it sees more than that.

Alexa, please play Ring on Fire TV

For a multinational corporation as bent on world market domination as Amazon, there is no problem that cannot be monetized. Such was the case when the theft of packages bearing the company’s smiling arrow logo became a common complaint in recent years.

In 2018, Amazon acquired Ring LLC, a start-up that Santa Monica inventor Jamie Siminoff founded six years earlier. Siminoff had the idea to implant doorbells with tiny motion-sensitive cameras so homeowners could watch and eavesdrop on whoever was outside without getting up from their couches. Siminoff said his wife loved the idea and urged him to pursue it.

So did Amazon, which gave Siminoff money in 2016 to pair his invention with the e-commerce giant’s Alexa cloud-based voice device, Echo Show smart speaker and Fire TV media player.

Once Amazon owned Siminoff’s company, it put Ring’s Neighbors social media app on iOS and Android products and introduced a whole array of new products, variations on a paranoid theme—putting homes and what passed outside them under constant surveillance.

The local news media even helped Amazon with its marketing, sharing questionable “reports” that Sacramento was a top destination for porch pirates, reports that originated from a company that advertised Ring’s products.

The California Department of Justice was reporting decades-spanning declines in crime rates, but statistics are no match for fear-based advertising. With each chiming Ring notification on their smartphones, customers were primed to suspect the world outside. For privacy advocates, it was both a canny marketing strategy and insidious form of classical conditioning.

“The truth is if you didn’t have Ring, you wouldn’t know if someone stopped in front of your house to tie their shoe,” said Matthew Guariglia, a policy analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundationin San Francisco. “But it’s going to make you feel like your house is under siege.”

Amazon also built on Ring’s friendly relationship with law enforcement, formalizing partnerships with nearly 1,500 agencies around the country, including more than 120 in California, most of them in Los Angeles and the Bay Area. The partnerships allow police to request video footage directly from Ring customers.

Guariglia, who has written extensively about unchecked surveillance, said police can make these requests in bulk, clicking and grabbing an area on a map, checking a box for the crime they say they’re investigating and firing a mass of automated emails to every customer in the area.

The emails can be a little deceiving. They come with two options: Share the footage or review the footage before sharing it. If a customer doesn’t want to turn over their footage, Guariglia said, they have to ignore the email, which might not seem very intuitive.

Amazon and other large tech firms have already faced backlash over their soft marketing to police, especially after the killing of George Floyd in May and law enforcement’s violent response to the demonstrations that followed.

In June, Amazon capitulated to a one-year moratorium on letting police use its facial recognition tool. A month later, the Electronic Frontier Foundation released an analysis showing that half the agencies Ring granted access were responsible for more than a third of the nation’s police killings, including the controversial deaths of Breonna Taylor, Alton Sterling and Sean Monterrosa.

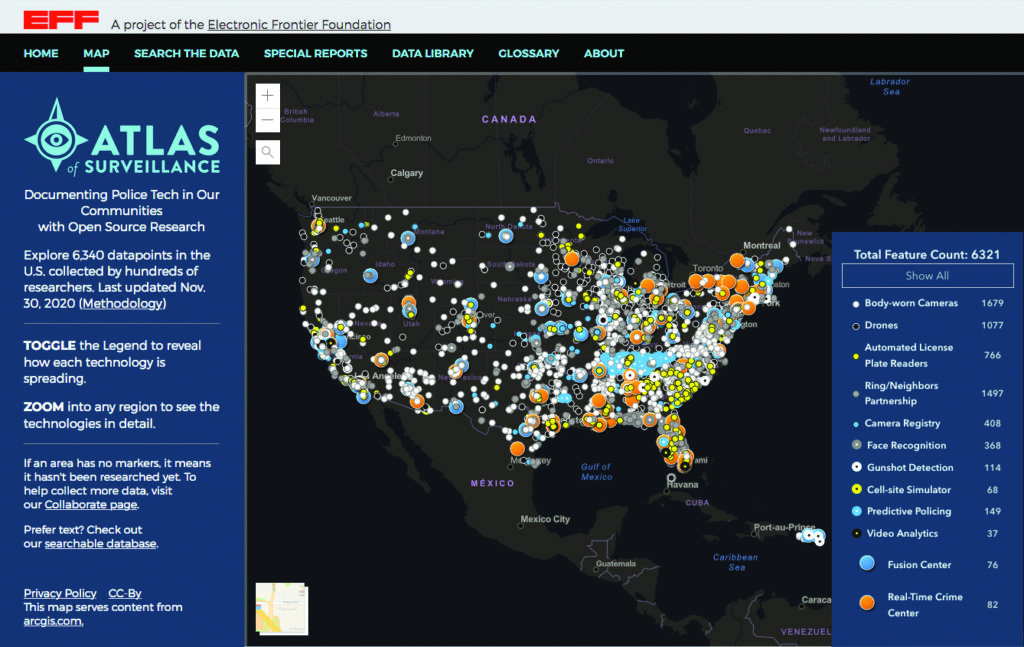

On Tuesday, the Sacramento Police Department became the latest local agency to join Ring’s controversial social network, Neighbors. In the region, Ring has cut deals with police departments in Elk Grove, Citrus Heights, Folsom, West Sacramento, Roseville, Rocklin and Auburn, according to EFF’s Atlas of Surveillance open source research project.

The Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office hasn’t signed onto a formal relationship with Ring just yet. But that doesn’t mean Sacramento’s largest agency doesn’t have a multitude of other surveillance tools at its disposal.

Screen of the crime

Several hours after Michael’s body was found inside his south county home, Detective Britton emailed Ring to ask if it saved footage from the dead man’s front door. He received a generic response minutes later. In response to a search warrant, the sheriff’s office received footage covering the previous two weeks.

Detective Bartilson testified that the footage showed a man and a woman arriving at the residence around 11:30 p.m. on April 8, 2019, six days before detectives made their grisly discovery. Surveillance footage from a home across the street showed the two arrived in a Lyft. The woman wore a knitted cap and sleeveless blouse. The man wore a hooded sweatshirt and gloves. He had a high, distinct hairline that receded halfway up his skull and made his features look smaller.

Less than an hour after they arrived, the pair left the residence with the victim. They got into the victim’s rental car, which pulled across the street to a community mailbox before exiting the view of the other house’s surveillance camera. Around 2 a.m., the men returned without the woman. The man with the high hairline appeared to hover behind the victim, looking around, Bartilson testified.

“As the victim opens the security screen door, the defendant is seen reaching over and locking the interior door lock to the bottom handle of the security screen door without the victim noticing,” Bartilson said.

Ten hours later, around noon that same day, the Ring footage showed the man with the high hairline exit the front door wearing different clothes. The footage showed him leaving the house a couple more times over the next 20 minutes, once with a trash bag and items in his arms and once to clean the doorknob with what Bartilson said looked like a pillowcase.

“To me that suggests that he is trying to get rid of any evidence—fingerprints, DNA—that would show he was there,” he testified.

Footage from across the street showed the man with the high hairline get into the victim’s rental car and drive off.

Ring didn’t record the murder. Indeed, it hadn’t captured a single violent deed or word. Damien Michael’s final moments, like most people’s, were scattered across unrecorded time. But for detectives, the Ring camera documented an unmistakable arithmetic: Two men entered a house. Only one exited.

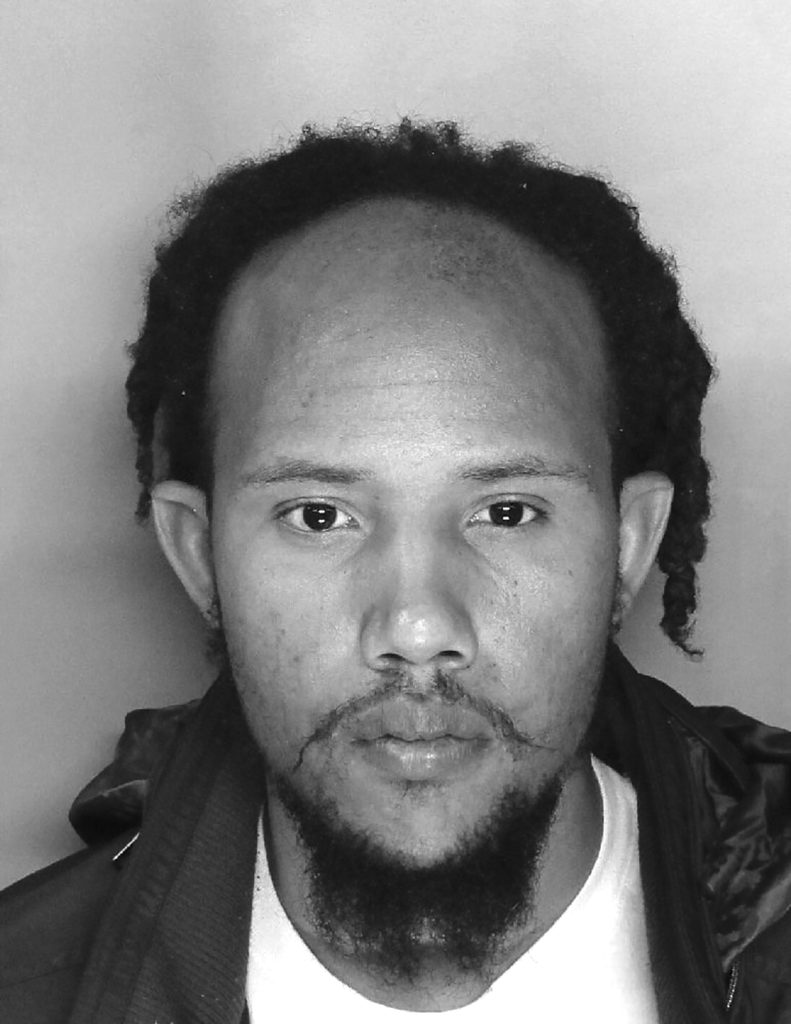

Detectives used the surveillance images of their suspect to create and distribute a flier to surrounding law enforcement. A sergeant with the county parks department contacted detectives and said he thought the man with the high hairline was someone he recognized. His name was Joshua Thomas Vaden, aka “King Josh.”

Vaden was a convicted carjacker and child molester who had done two stints in prison, online court records show. He was also on parole, so detectives sent their images to Vaden’s parole officer, who confirmed the park ranger’s ID. And another thing: Vaden was wearing an ankle monitor that showed him at the victim’s house on March 25, 2019, the P.O. said, weeks before the murder. That was also the last date the ankle monitor was active.

The assumption was that Vaden cut it off.

The eyes have it

In November 2019, sheriff’s deputies on patrol in North Highlands used facial recognition technology to arrest a young Black woman for allegedly lying to them about her name and carrying an open alcoholic beverage.

The deputies were able to do this because their agency contracts with a South Carolina tech company called DataWorks Plus, which stockpiles tens of thousands of mugshots and other digital images in a server that some of California’s biggest law enforcement agencies contribute to and access.

The use of such an invasive technology to make such a low-level arrest is not what the sheriff’s office advertised when it secured county supervisors’ approval to expand its relationship with DataWorks Plus three years ago.

“This increased functionality will help to more effectively identify individuals with outstanding warrants, fugitives, and others wanted by law enforcement,” Sheriff Scott Jones wrote in a 2017 staff report.

That’s what law enforcement officials always say, according to experts on policing and surveillance.

“A lot of these tools are sold initially to find potential murders or investigate acts of terror and that sort of thing,” said Ángel Díaz, counsel for the Liberty & National Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. “Setting aside whether that’s accurate … it also often times becomes the case that they’re used in more ordinary situations.”

Díaz observed incidents in New York where facial recognition technology was used to arrest people for petty thefts, such as stealing a six-pack of beer or pirating an Amazon package. More concerning to him, though, is how flawed surveillance tools are misused or abused.

Innocent people have been pulled over, held at gunpoint and detained because of mistakes made by facial recognition software and automatic license-plate readers. Facial recognition technology’s documented biases in accurately identifying women, children, the elderly and people of color informed Gov. Gavin Newsom’s signing of a bill last year stalling law enforcement’s ability to use the technology for three years.

But privacy experts warn that improving the flaws in the technology won’t improve humans’ ability to use it responsibly.

In June, U.S. Customs and Border Protection got caught flying a Predator drone over a Minneapolis demonstration sparked by Floyd’s death.

The New York Times reported that Border Protection’s parent agency, the Department of Homeland Security, “deployed helicopters, airplanes and drones over 15 cities” where demonstrations occurred, “logging at least 270 hours of surveillance.” All that footage, The Times reported, “was then fed into a digital network … called ‘Big Pipe,’ which can be accessed by other federal agencies and local police departments for use in future investigations.”

These surveillance tactics weren’t employed during the “reopen” protests against COVID-19 stay-at-home orders, noted Olugbenga Ajilore, a senior economist at the Center for American Progress who previously studied police militarization at the University of Toledo. “Which raises the question: How are these tools being used and who are they being used against?”

The Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office has spent more than nine months declining to answer these questions, breaking California’s public records law in the process.

Person to person

Detectives’ big break in the Michael case came from an ordinary human.

According to homicide detective Kevin Lawrence, Edwin Paz-Ortiz was drinking beer outside a liquor store in Anaheim around 9 p.m. on April 9, 2019, when a man exited the store and the two struck up a conversation.

Paz-Ortiz had been drinking since earlier that day and was inebriated, Lawrence testified, but not so buzzed that he didn’t notice the stranger had an unnaturally high hairline. It was Vaden.

The two quickly bonded over talk of beer, and Paz-Ortiz got into Vaden’s car and the two drove to a bus stop where Vaden allegedly copped some meth. They stopped for gas, then rode to a spot where Paz-Ortiz thought they might be able to chat up some women. They struck out and hopped onto Interstate 5 headed for Mexico, Lawrence testified.

Vaden and Paz-Ortiz stopped in San Diego and parked behind a Denny’s, where Paz-Ortiz started to have second thoughts about his new friend. Vaden was acting strange. He talked about robbing a liquor store or bank and handed Paz-Ortiz his cellphone and ID and told him to smash up the ball of meth. Paz-Ortiz then saw how frustrated Vaden got when he couldn’t open the trunk of his car and began suspecting he’d been joy riding in a stolen vehicle.

Paz-Ortiz told Vaden he needed to hit the can, but instead ran to a nearby gas station and asked an employee to call the police. Paz-Ortiz still had Vaden’s ID, and gave it to the cops when they arrived. Outside the Denny’s, Vaden and the victim’s rental were gone.

Later, detectives reviewed the security footage from the service station and saw Vaden, still in the clothes he wore when he left Michael’s home, come and go in the victim’s rental car.

On May 13, 2019, about a month after he canvassed the murder scene, Detective Britton received word that Vaden was in Tijuana, Mexico. Vaden was extradited to the United States, where Britton interviewed him at the San Diego County jail.

Three days later, Vaden was booked on a felony murder charge into the Sacramento County jail, where he’s been held ever since.

Whether the prosecution has more than what it presented during September’s preliminary hearing is unclear. No confession or physical evidence linking Vaden, now 32, to the murder was offered, but preliminary hearings only require enough probable cause for a trial.

That trial is tentatively set to begin on Dec. 21, though Vaden’s public defender expects it to be delayed until early next year.

So much for transparency

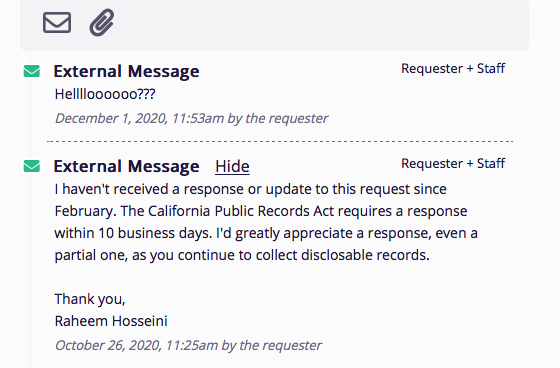

In February, after a sheriff’s spokeswoman didn’t respond to questions about last year’s drinking in public arrest, SN&R submitted public records requests seeking to learn how the sheriff’s office uses facial recognition data and whether it’s had any contact with a company called Clearview AI, which scrapes social media to create a massive library of faces for law enforcement.

The California Public Records Act gives agencies 10 days to determine if they possess the records being sought and a 14-day buffer if they need more time. Except for automated confirmation emails when the requests were submitted, the sheriff’s office has stayed silent for 10 months.

One records request the agency did answer concerned the “Sheriff’s Electronic Eye.” S.E.E., as it’s also called, is a voluntary camera registry program that asks residents and business owners with personal surveillance systems to register their locations so that when a crime occurs, detectives can quickly determine who might have video evidence and request it.

“It’s just a list,” explained Elk Grove police Sgt. Jason Jimenez, whose department has its own camera registry. “Some people think it gives us access, but it doesn’t. It just saves us some time having to walk that street” looking for cameras.

The S.E.E. program has enrolled 1,754 registrants since 2014, according to the sheriff’s response to SN&R’s inquiry. As for the number of registrants the agency has contacted or the number of videos it has recovered, the sheriff’s office stated, “No responsive records exist.”

That either means the S.E.E. program has been a total flop or that the sheriff’s office doesn’t believe it has to say how it administers it. A sheriff’s spokesperson didn’t respond to requests seeking clarification.

It’s also unclear whether the proliferation of newer technology has improved law enforcement’s ability to solve crimes.

The sheriff’s office—which has facial recognition technology, gunshot detection sensors, license-plate readers and a technology that can intercept and locate cellphone signals—was unable to solve more than 60% of violent crimes last year, according to the California Department of Justice.

The agency has improved its ability to make arrests in motor vehicle thefts over the past decade, closing 41% of cases last year, a 22-point improvement from 2010.

The Sacramento Police Department—which has drones, license-plate readers, gunshot sensors, observation devices and a surveillance command center that can access them all—cleared only 40% of violent crimes last year and less than 10% of motor vehicle thefts.

The Elk Grove Police Department partners with Ring, operates drones, runs a camera registry and its own observation center with more than 300 license-plate readers, traffic feeds and cameras on city buses. It cleared more than half of violent crimes and 11% of motor vehicle thefts.

“There’s really no evidence that surveillance prevents crime,” said EFF’s Guariglia, “especially with Ring.”

But even if there was, Díaz of the Brennan Center contended, results shouldn’t be the only consideration. Not unless Americans want to live in a surveillance state.

“It might be useful for police to come into your house whenever they want to solve a crime, but we don’t do that,” Díaz said. “Usefulness isn’t the only thing.”

Jimenez noted that his suburban department, which had no murders of its own last year, was able to make an arrest in a Livermore homicide last August, when the suspect’s vehicle passed a fixed license-plate reader in the city, which alerted staff in the observation center. Personnel located and tracked the vehicle using traffic cameras and sent real-time updates to responding officers. Jimenez said the cameras were able to determine there was only one person in the car, which influenced how officers conducted the vehicle stop that led to the arrest.

“That was helpful,” Jimenez told SN&R. “With the abundance of cameras now, that just gives us the ability to hopefully capture something that will help detectives solve those crimes.”

But for every one of those cases, privacy experts say there are examples where surveillance technology has been used to racially profile, harass or monitor someone who didn’t deserve it.

“The question is where is that line?” said American Progress’ Ajilore. “I don’t even think we’ve adequately discussed that issue.”

A Biden administration should look more favorably on civil liberties than the Trump administration, but both the president-elect and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris, California’s former attorney general, have stressed they’re not in favor of defunding police.

That means it might fall on local officials to determine how much privacy is worth preserving.

Before the pandemic, cities across the country were beginning to rein in their police departments’ ability to acquire new technologies without public hearings, said Díaz.

“There are a number of jurisdictions that are starting to pass those laws and correct some of the imbalances we’ve started to see,” Díaz said. “But in a lot of places, these tools are being used in the dark.”

The Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office secured its facial recognition tech without the public’s knowledge and has refused to tell the media how it’s using it. For Díaz, that’s reason enough for a final warning.

“Police are human and humans can do bad things,” he said. “I don’t think we’ve fully grappled with the whole gamut of things that can and are going wrong.”

Be the first to comment on "New surveillance tools allow cops to spy on everyone—including you"