Is county undercounting its COVID-19 deaths?

Sacramento County issued 1,400 more death certificates between March 1 and Aug. 31 this year than it did during the same period last year, suggesting the death toll from the novel coronavirus could be significantly higher than previously known.

Officially, Sacramento County identified 325 people who died from COVID-19 during the first six months of the pandemic, with seven more deaths since the start of September.

That pencils out to a 1.7% mortality rate for the 18,813 people in Sacramento confirmed to have contracted a virulent respiratory illness that has killed nearly 190,000 Americans and rewritten modern life around the globe.

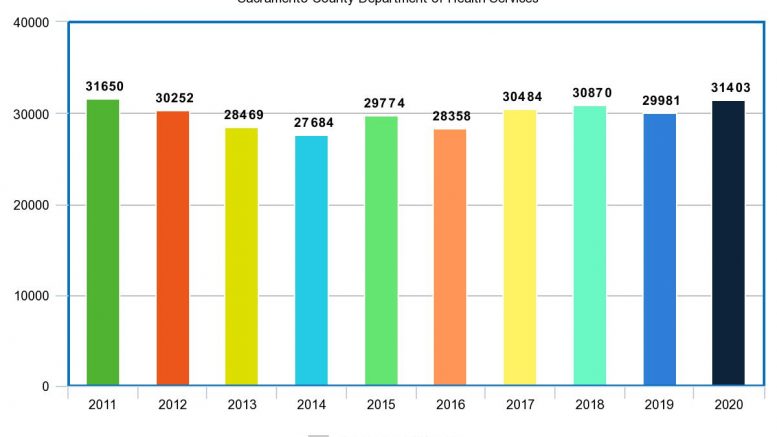

But data received through a public records request shows Sacramento County issued 31,403 death certificates over the past six months—1,422 more than during the same span last year, 533 more than in 2018 and 919 more than in 2017.

That’s more deaths during this period than Sacramento County has experienced in a decade.

The numbers suggest the pandemic could be vanquishing more lives than attending physicians, medical examiners and pathologists have thus far been able to confirm.

Determining cause of death

Ironically, the sharp increase in people dying means it will take longer to determine what killed them.

In the U.S., COVID-19 death certificates are typically handled by physicians unless the death occurs outside of hospitals, the president of the National Association of Medical Examiners told Scientific American.

For patients who die in intensive care units after a days- or weeks-long bout with COVID-19, assigning cause of death is relatively straightforward. That prospect gets trickier for people who die at home, on the streets or shortly after arriving in an emergency room. And while autopsies could provide some certainty, they’re often not done for victims of communicable viruses.

Twenty-seven states require autopsies “if the cause of death is suspected to be from a public health threat, such as a fast-spreading disease or tainted food.” California isn’t one of them.

Even without required autopsies, figuring out why someone died can be a time-consuming process.

Sacramento County Coroner Kimberly Gin said her office coordinates with pathologists and investigators to determine causes of death, a process that could take several weeks even before COVID-19 complicated how she does her work.

“It takes us time to do all these things normally and as you can imagine from the numbers below this process is made worse by the increase,” Gin explained in an email.

Gin said an investigator assigns an initial death classification, which helps determine what exams and tests a doctor conducts. Even before the pandemic, it could take months for a final manner of death to be issued.

Because of the increase in deaths and the delay in determining what killed them, Gin said she can’t yet pinpoint why death certificates jumped 4.5% compared to last year.

“I suspect that we are going to end up saying that the increase is due to a multitude of reasons,” she wrote. “I know that we have seen an increase so far this year in homicides definitely, that number is concrete.”

While homicides have been trending upward since January, there were only four more homicides than last year from March through August, when COVID-19 has been active. That means homicides don’t come close to accounting for the 1,400-plus surge in death certificates.

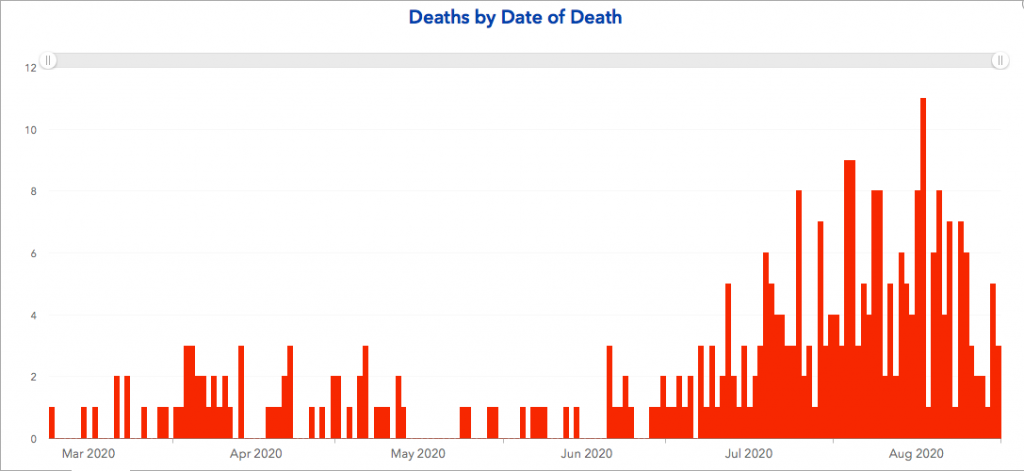

Meanwhile, the data shows that Sacramento County experienced by far its deadliest April, July and August—when infections were at their worst—in four years.

“That’s pretty significant,” said Bob Erlenbusch, executive director of the Sacramento Regional Coalition to End Homelessness.

Lessons from the vulnerable

Erlenbusch works with the coroner’s office to publish an annual tally of homeless deaths. The latest report showed 138 people died while experiencing homelessness in Sacramento County last year, the most on record and a 74% jump since the coalition began issuing these reports in 2003.

Because it can take several months to notify homeless people’s next of kin, these reports are, by necessity, a look back rather than a real-time tracker of deaths in Sacramento’s homeless population, so Erlenbusch doesn’t yet know if more people are dying on the streets this year.

Generally speaking, Erlenbusch said, homeless deaths rose as more Sacramento residents fell on hard times. But estimates indicate the county’s general population increased at a rate of less than 1% last year, which wouldn’t be enough to explain an almost 5% increase in death certificates.

“You can’t explain it away,” Erlenbusch said.

Acknowledging the undercount

The prospect that COVID-19 is deadlier than we know has already been accepted in certain circles.

The New York Times used data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to show the national death toll from the coronavirus had likely surpassed 200,000 in late July, when the official count was approximately 140,000.

Tracking of unusual deaths has led groups such as the World Health Organization to conclude that COVID-19 has likely killed more people than reported.

“Some of that excess mortality is probably COVID disease that was not recognized or reported,” Bruce Aylward, senior adviser to the director-general at WHO, said during a Friday briefing, CNN reported.

President Donald Trump and Republicans have repeatedly downplayed the threat of COVID-19 to justify reopening the country against the advice of public health experts. Some have embraced conspiracy theories to claim deaths are much lower than reported, even with mounting evidence to the contrary.

But they can’t erase the fact that an unusually high number of people have died during the height of the pandemic compared to years past.

“We are seeing an increase in deaths this year,” Gin said. “I am hearing similar issues across California and the nation from other [coroners and medical examiners].”

Be the first to comment on "Exclusive: Death certificates spiked in Sacramento during the pandemic"