The Sacramento man was suffering a medical emergency when police helped paramedics restrain him. He died a week later.

Video footage of George Floyd dying under a police officer’s knee last week ignited massive demonstrations around the world and revived the agonizing debate about law enforcement’s treatment of people of color in the United States.

The family of a Black Sacramento man says their loved one was the victim of similar mistreatment—three months before Floyd’s killing—and deserves similar outcry.

Reginald “Reggie” Damone Payne died in Sutter Medical Center on March 3, seven days after a filmed encounter with paramedics and Sacramento police resulted in the 48-year-old diabetic losing consciousness in his home.

Payne’s mother and sister say their loved one, who underwent dialysis treatment earlier that day, simply needed a dose of glucose for his low blood sugar. Instead, Fire Department personnel summoned police to first restrain Payne before they would administer care.

“They were lolly-gagging,” Janine L. Jefferson, Payne’s sister, told SN&R. “He was saying he couldn’t breathe.”

The Police Department released edited footage from three officers’ body cameras on April 16, more than seven weeks after officers responded to the one-story home in South Sacramento. The footage doesn’t reveal anything as brazenly cruel as what happened to Floyd, who can be heard asking for his dead mother as Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin ground his knee into Floyd’s neck for eight minutes. On Wednesday, Minnesota’s attorney general elevated the charge Chauvin faces to second-degree murder and was reportedly considering prosecuting three other fired officers with aiding and abetting Floyd’s murder.

The Sacramento County Coroner’s Office is investigating Payne’s death and his mother says she’s spoken to homicide detectives about the incident. But she and Payne’s sister say the body-cam footage shows a callousness toward someone who needed urgent medical care. And they say that, unlike the 46-year-old Floyd, whose death has sparked demonstrations and clashes with police across a nation slowly emerging from the coronavirus pandemic, the fact that Payne died off-camera denied him similar recognition.

Who was Reggie Payne?

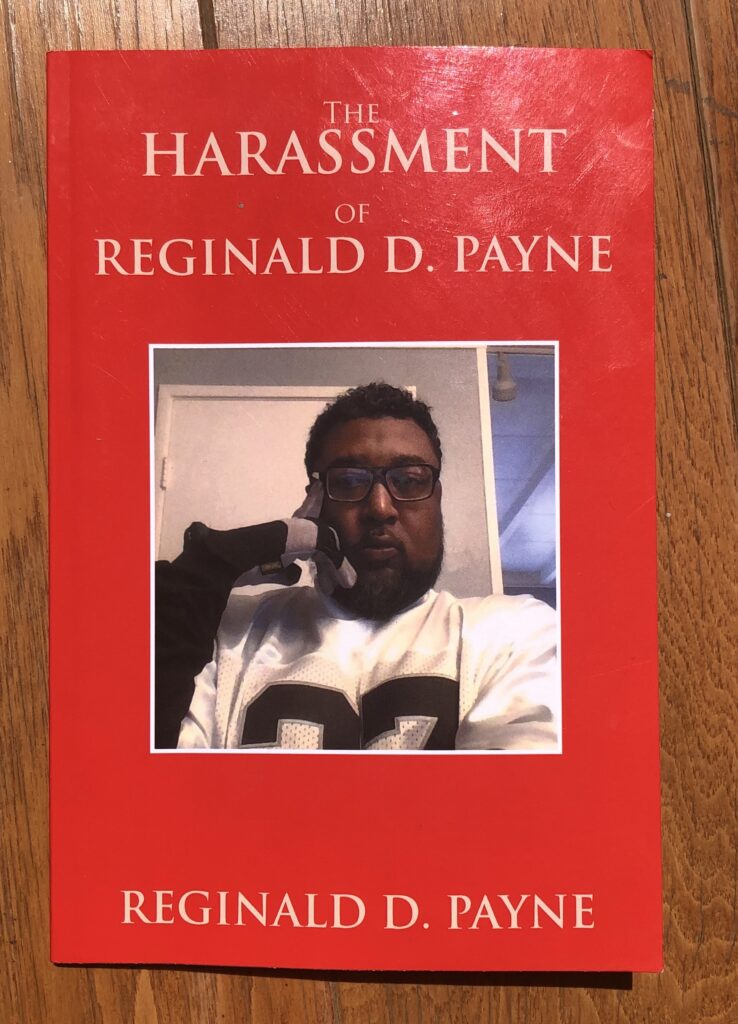

Harriett Jefferson said her son was in college when he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Payne published a short memoir about living with his disorder in 2018, titled The Harassment of Reginald D. Payne. In the early chapters, Payne writes of voices inside his head taunting him with insults and slurs, often when he tried to sleep:

“How am I supposed to believe in an America and her dreams, when my own are nightmares?” he writes in one chapter. In another, when the word “chump” has been ringing in his head in 15-minute intervals, he pleads, “Please, I’ll be a chump all day for a full 8-hour sleep night….”

Still, Jefferson says, her son was resilient. He attended Grambling State University, a historically Black public university in Louisiana, where Payne writes that he was once jumped by several members of the football team and “took my beating like a man,” years after he faced similar tests on the streets of East Oakland. Jefferson said that her son, a self-professed “sports nerd,” wrote for his college newspaper and was a calming influence, once spending hours on the phone consoling his cousin after officers in Texas pulled him over for an expired registration tag and drew their guns.

According to Payne’s book, he moved from Oakland to Sacramento in 2006 and lived in a small Stockton apartment in 2017. But he eventually went to live with his parents near Hollywood Park, in part, because of his health-care needs. He received dialysis treatment three times a week and often talked through the four-hour sessions, Jefferson said, forgetting to eat. That’s what Jefferson said happened on Feb. 5, when Payne began shaking from low blood sugar and she called 911. Jefferson said she made the same call once before when her son acted “a little goofy” and the EMTs who responded “were really nice.” She said the treatment her son received this time was “much different.”

“This time Reggie sat on his couch, offered his hand to the Fire Department [paramedic] and the guy just looked at him,” she told SN&R.

Jefferson said her son refused to be treated by someone who wouldn’t even shake his hand. The Fire Department called in the police.

What the videos show

In a press release, the Sacramento Police Department states that the city Fire Department responded to a medical emergency at a residence on the 5300 block of 25th Street and encountered an “uncooperative” man in distress.

Body-camera video shows an officer walking up a driveway toward a carport where a few paramedics flank a yellow-framed gurney under a harsh, squinting light. It’s nearing 8 p.m. that Tuesday. A paramedic with rolled-up shirt sleeves and purple medical gloves briefs the officer. “Hey, he’s in the back. We just need you to get him cuffed, restrained or talked down so we can check his [inaudible],” the paramedic says.

“OK,” the officer replies.

“Alright? Have at it.”

“He’s a big boy?” the officer asks.

“Big boy. That’s why we called you.”

The paramedic estimates Payne is 6-foot-6 and weighs as much as 350 pounds. Janine Jefferson said her brother was 6-foot-2 and down to 220 pounds due to his dialysis treatments. The officer lets out a tight laugh. “Is he mobile or no?”

“Oh yeah, he moves,” the paramedic says. “If he wasn’t mobile, we wouldn’t need you.”

There’s a little banter from the paramedic and the officer asks if the patient has threatened them. Another paramedic breaks in, describing their patient as “just very resistant.” The lead paramedic adds that he’s “super agitated, swinging his arms and legs everywhere.”

The officer asks if the patient knew the police were coming.

“He’s not comprehending much,” one of the paramedics says.

Payne’s sister and mother take issue with how paramedics portrayed Payne to officers.

“They lied. They really lied,” Harriett Jefferson said. “They had the Police Department assuming that this is this big Black man spitting.”

In the video, the officer decides to wait for backup, which is on its way. Told that the patient is “salivating,” he pulls on a pair of black gloves and retrieves a spit mask from his trunk. A second officer arrives. They walk back to the house. On the way, the first officer relays what the paramedics told him about the “big boy” who flails and spits. Before they go in, the officer seeks guidance.

“Like, I’ve never done this. How do you—like you just literally cuff him up and hand him over if we have to get to that point, or what?”

The second officer responds as he pulls on his gloves near shoulder-high plants and a wood fence. “Yeah. I mean, we may not have to get to that point, but if he keeps flailing and stuff while we’re trying to get him under control then, yeah, we’ll put him in cuffs and put the spit mask on if he wants to spit.”

The second officer briefs the third officer to arrive, and tells him they’re just there to help paramedics get their patient to the hospital. “I don’t think there’s any crime here,” he says.

They enter the house, crossing laminate floors through the kitchen and a dining nook. Harriett Jefferson tells the officer what her son has eaten that day, trying to relay what she believes is pertinent medical information. The mood is casual.

The officers move into the living room and find Payne, unable to keep his body from spasming. He slides off the couch as the officers talk to him, and one officer grabs him from behind as another takes an ankle. Payne calls for his father as he’s wrestled onto his belly and handcuffs click around his wrists and ankles. The officers tell him he’s all right. Payne grunts compressed air and bellows words into the floor.

The paramedics come in. “Who’s the rodeo star here?” someone cracks.

An officer rubs Payne’s back. Payne calls for his parents. A paramedic takes silver shears to his green sweater. Payne’s mother tries to comfort him. He makes thick, guttural sounds and whimpers.

A paramedic pats his back and says, “You’re all right.” He injects a needle into his shoulder where his sweater was cut away. About six minutes after he’s put onto his belly, Payne stops moving. One of the officers asks if his heart is still beating. A gloved hand feels around his neck. “Yeah,” a man says. Someone chuckles with relief.

At the dawn of a new crisis

The paramedics begin trussing Payne’s hooked wrists and ankles in white binding fabric. His track pants have fallen down past his boxers. As five paramedics lift their motionless patient onto a gurney and bind him some more, a male voice comes across the radio. The voice says the Kaiser Permanente South Sacramento has a patient with coronavirus symptoms, and advises emergency responders to either avoid that location or “mask up” before going in. “Still getting more info, but they’re taking it pretty serious down here,” the voice says.

Officers relay the message to the paramedics, who mention their new screening protocols. The shadow from an overhead ceiling fan swings thick tendrils around the room. Their patient waits on a gurney. His mother asks about him. “He’ll be right as rain when he comes home,” someone tells her.

Payne never woke up. The Police Department says that paramedics began CPR in the ambulance. His family says he suffered multiple strokes and irreparable brain damage. He officially died a week later at Sutter Medical Center, but Harriett Jefferson believes the son she felt so close to had passed before that.

“He was gone before he left this house,” she said.

She and her daughter wonder how things would be different if the emergency responders were more respectful and less afraid. They hope there’s room in the national mourning over George Floyd for their private grief. Reggie Payne’s name has already rang out in some protests, his family says.

“His nieces and sisters in other cities are out there with his sign as well,” Harriett Jefferson said. “Because Reggie would want this.”

Payne contemplated his death in his memoir, writing that he was scared of being forgotten:

I often wonder how many other black men have suffered or been tortured over the years, dead and gone, and no one even knows or knew. Personally, one of my worst fears.

No one will even know my struggle when I’m not here.

Reginald D. Payne

These ofays have a depraved indifference to the lives of NUBIANS. You are free Reginald Damone Payne, Rest In Paradise.