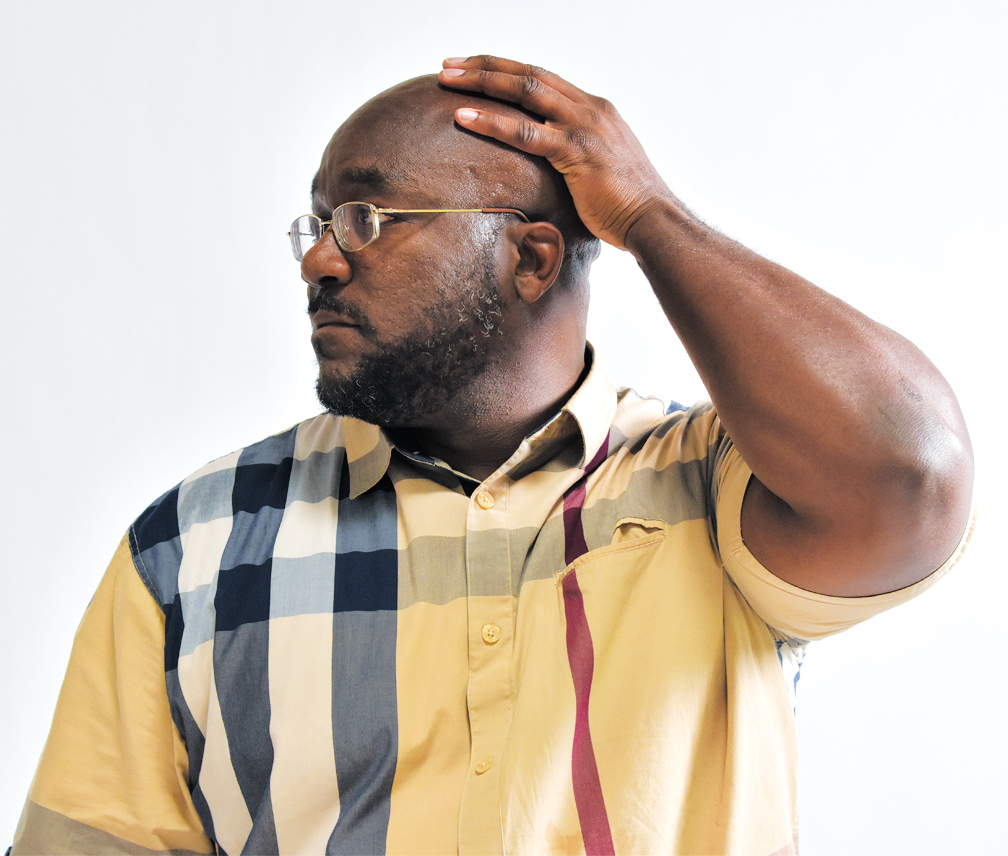

Two Sacramento detectives denied Tio Sessoms his right to an attorney. So he became his own advocate—in prison.

Somewhere in Oklahoma:

The walls of the jail’s interrogation room closed in. Tio Dinero Sessoms wore the 8-by-10-foot box like an oversized coffin. He compacted his 6-foot-1 frame into a chair and waited. The 19-year-old from Sacramento remembered his father’s words:

“I’m not a criminal,” he reminded himself. “I know I want to talk to a lawyer.”

It was November 1999. Sessoms was a long way from home and in a great deal of trouble.

A month earlier, at least two men broke into the mobile home of a Sacramento pastor named Edward R. Sheriff. The burglary became a home invasion became a murder. Someone stabbed Sheriff in his neck and upper body until the preacher’s blood stained the killer’s shoes.

Sessoms said he got a call from his father telling him the cops in Sacramento were looking for him. His face had been plastered all over the evening news. Sessoms was staying with his girlfriend in Oklahoma, a state that resembles a clenched fist with its finger pointing back to California. His dad told Sessoms to turn himself in, and offered some sage advice: Don’t talk. Lawyer up.

Sessoms listened to his dad.

Two Sacramento city homicide detectives didn’t.

They denied Sessoms’ legal right to an attorney. The fruit of that poisonous interrogation almost 20 years ago put the teenager behind bars for a murder he didn’t commit. Sessoms lost his youth in prison, but not his hope. A kid without a high school diploma cracked the law books and wrote a legal brief that ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court—twice.

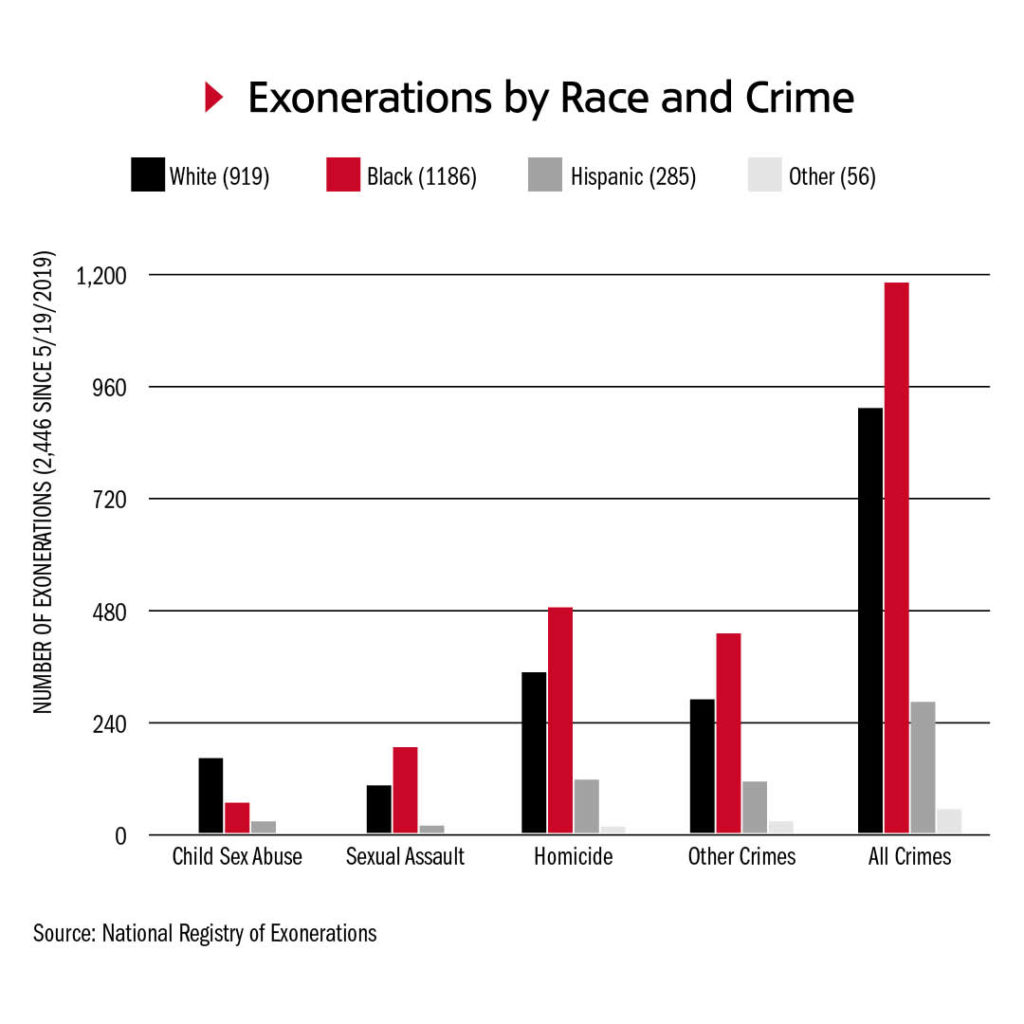

It’s sometimes dismissively said that America’s prisons are filled with innocent people. There are at least more than 2,400 instances of that being the proven case since 1989, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, compiled at Michigan State University and UC Irvine. The wrongfully convicted have sacrificed more than 21,000 years combined to a criminal justice system that got it woefully wrong.

Nearly half of the unjustly incarcerated are black, like Sessoms.

Sessoms, however, doesn’t think what happened to him was about race. He insists he was undone by corner-cutting detectives, overly aggressive prosecutors, an incompetent public defender and an unsympathetic judge. In short, he believes the whole damn system is to blame.

“You can’t rebuild a system that’s shattered,” Sessoms told SN&R. “The only way we can fix it is by building it all again.”

Now 39, the new father said he wants to help create that new justice system. But only after he brings the old one crumbling down.

You have the right to incriminate yourself

No clock on the wall. Time dragged. Sessoms shivered. The box was an icebox. Its door opened. Two clean-shaven white men entered. They wore old jeans and old button-ups. Sessoms remembered thinking these cops weren’t paid enough. A video camera recorded the scene. The older one spoke first.

“Tio, I’m Dick,” Det. Richard Woods said.

“How you doing, all right,” Sessoms said. “You already know me.”

Det. Patrick Keller introduced himself next. He had Sessoms swap seats. It was cramped. Sessoms maneuvered while the two detectives crowded the open door. The detectives closed the door, resealing the box. Sessoms said something as he sank into the suspect’s seat. Woods didn’t catch it. “Huh?” he said.

Sessoms repeated himself. “I’m glad you fellows had a safe flight out here,” he said.

“So are we,” Keller replied.

“Well, we want a safe one back, too,” Woods cracked.

Woods tried to move things along. Sessoms interjected. “There wouldn’t be any a—a lawyer present while we do this?” he asked.

Woods hemmed, “Well, uh, what I’ll do is, um.”

Sessoms interjected. “Well, that’s what my dad asked me to ask you guys—uh, give me a lawyer.”

Four days earlier, on Nov. 15, 1999, Sessoms’ father called him from Atlanta, where most of the family had relocated. He told his son he was wanted for a cold-blooded robbery-homicide in Sacramento. A victim, a minister, stabbed two dozen times. There was an “armed and dangerous” bulletin out for the younger Sessoms. He told his dad he knew nothing about it.

Sessoms was in Langston, Okla., with his girlfriend. His dad arranged for him to turn himself into a police officer named David Hinds Jr.

Hinds and his partner did things by the book, court filings state. When Sessoms informed them he wouldn’t be making a statement, they stopped trying to get one. And when a Logan County sheriff’s deputy tried “pressuring” Sessoms during booking, Sessoms remembered Hinds stepping in and saying, “Absolutely not.”

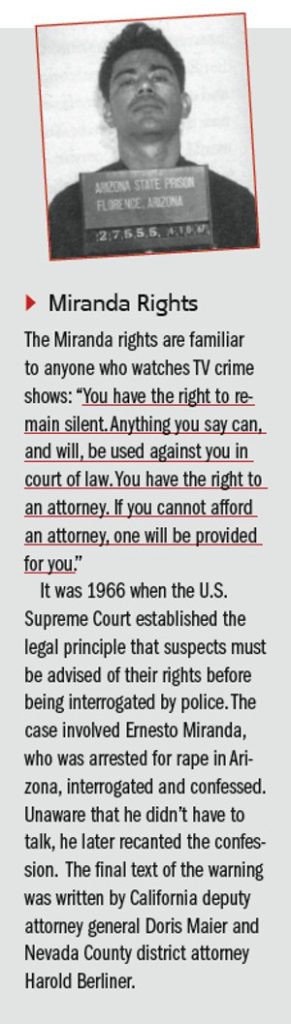

Sessoms had been given the Miranda warning, a term that’s become shorthand for a 1966 Supreme Court decision that established the rights of suspects in police custody. Sessoms had the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney. He invoked those rights.

That invocation protected Sessoms as he was transported about 40 miles south to a jail in Oklahoma City, where he waited four days for two Sacramento detectives to claim him. The legal protection followed him into the interrogation box, where he waited some more. It re-announced itself when Sessoms said the words, “get me a lawyer,” to Woods and Keller.

But that’s where it gave out.

Detective Woods used an old interrogation trick: Redirect, obfuscate, keep the conversation going. He kept the conversation alive for 20 minutes, and pulled out a tape recorder to show he wouldn’t play any “switch games” with Sessoms’ words. He said he and his partner already knew “what happened” from Sessoms’ alleged co-conspirators. He said the two men told them Sessoms didn’t stab anyone. Woods implied he believed that. Then he closed the loop. An attorney would only get in their way.

“If you said you didn’t want to make any statement without an attorney, we’re not really going to be able to talk to you and get your version of it,” Woods counseled.

Only after the long preamble did Woods re-Mirandize Sessoms.

Sessoms paused. He shrugged his shoulders and said, “Let’s talk.”

Anything you say…

According to the version of the crime that Sessoms’ appellate attorneys stipulated to the district court in 2006, it was supposed to be a simple burglary.

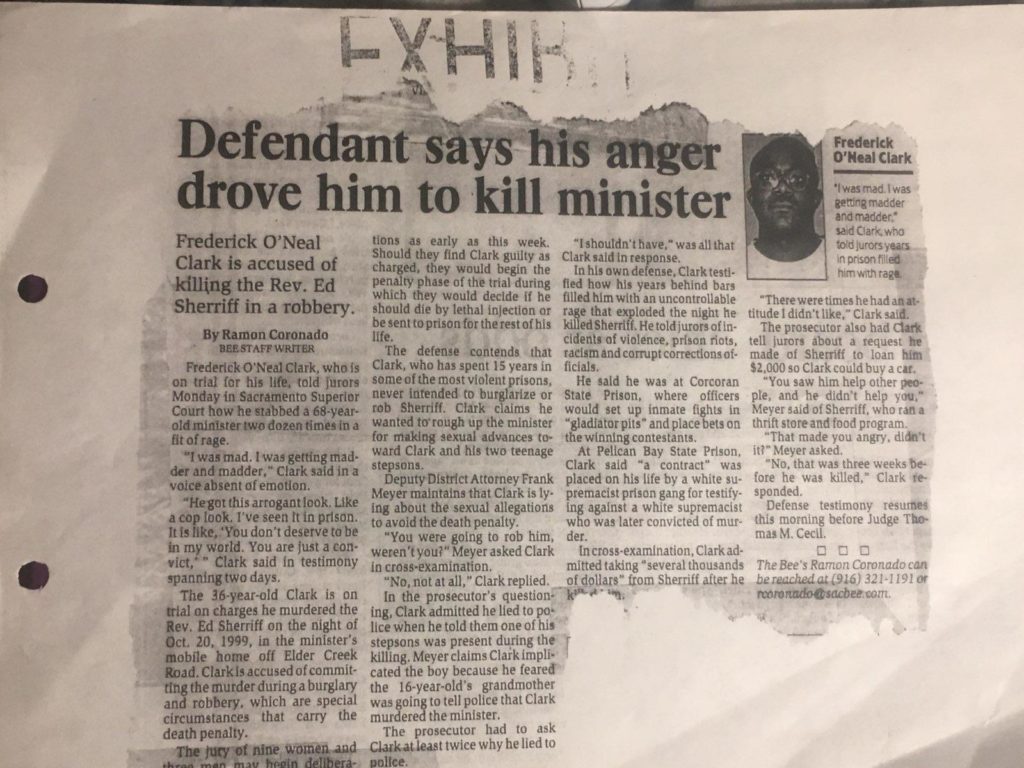

On the night of Oct. 19, 1999, Sessoms arrived at a house on Rancho Adobe Drive occupied by Frederick O. Clark, a small, stocky man in his early 30s. Clark had already done prison time for a 1990 case resulting in felony convictions for assault with a deadly weapon, sexual battery, statutory rape and false imprisonment, online court records show.

Clark was weird and intense, Sessoms told SN&R in a recent interview. Clark got lost staring at the wall like circuits misfired inside his head.

Sessoms didn’t know Clark well. Sessoms knew a guy who knew Clark, who knew of a place on Elder Creek Road with money stashed inside. The house would be empty, so the heist would be easy: Get in, get out, split the loot. Adam Wilson, Sessoms’ junior high classmate and Clark’s roommate, was already in the plot and invited Sessoms earlier that day, prosecutors said. Sessoms and Clark picked up Wilson and drove to the mobile home park where Ed Sheriff lived.

According to a 2014 Sacramento Bee article, Sheriff was an associate pastor at the Cathedral of Promise Metropolitan Community Church at Mather Field and a gay activist who ministered to AIDS patients and ran a thrift store and food program in Oak Park. One of the people he reportedly helped was Clark.

In their detailed summary to the district court, Sessoms’ attorneys portrayed him as a reluctant participant as soon as the would-be burglars arrived at their destination. Clark idled outside the gate of the mobile home park and punched in a code. The gate didn’t lift, so he parked across the street and jumped a fence. Sessoms pulled Wilson aside and told him something was off about Clark. Sessoms suspected he was hiding something. Maybe they shouldn’t go through with it. But after a few moments, Sessoms climbed the fence and Wilson followed.

Sessoms told SN&R this isn’t the way it happened. Not at all.

…can and will be used against you

Sessoms told SN&R he had spent some time in juvenile hall by age 19, but not for anything major.

The way Sessoms tells it, he was a reluctant cog in Sacramento’s school-to-prison pipeline. He said he was kicked out of Valley High School after stepping to a guy who disrespected his sister. He did a stint at a probation school before transferring to Kennedy High. Things were looking up. He said he was getting decent grades, playing football and gearing up for a breakout senior year.

But there was this security guard who hassled students. Sessoms said he told him, “Get your bitch ass to class.” Sessoms said he took offense and almost put hands on the man. He didn’t get the chance. The guard snitched him to the principal’s office. Sessoms was expelled with just a few weeks left in the semester.

“My life kind of shifted, like for the worse,” Sessoms said.

That summer, Sessoms and a buddy stole a car. He did three weeks in juvenile hall, he said. He got out on July 5, 1997, two days after his 17th birthday. His dad kicked him out. Less than two months later, Sessoms was back in juvi for receiving stolen property and evading the police. The intake officer offered him his one phone call. He brooded.

“Nah, I’m good,” he said. “Let me just take my shower and lie down.”

The intake officer insisted. He called Sessoms’ dad and held out the receiver. The big, sullen kid wouldn’t take it. His friends’ parents always had nice things to say about him, but not the old man.

“There was a lot of anger between me and my dad,” Sessoms said.

They patched things up at Sessoms’ first juvenile court hearing. The father counseled his son. Keep your head down. Take care of business. Come home.

Sessoms was sentenced to four months at the Sacramento County Boys Ranch. He did well and shed time from his sentence. He came close to getting his GED, but fell 13 points short of passing, he said. The setback wounded him.

“That hurt my feelings, too, because I was ready,” he said.

Sessoms had already given up on getting a college football scholarship. Now his consolation dream of playing ball in city college was fading. He got out two days before Christmas.

The Boys Ranch hooked him up with a drywall job. He carried sheetrock panels up flights of stairs. He lugged the gypsum boards that prop up the discount hotel behind the McDonald’s on Richards Boulevard.

He lost his transportation and then the job. He replaced it with a warehouse one loading seafood into trucks 8 p.m. through sunrise. Riding the light rail back, he noticed the morning commuters making stink faces. He averted his eyes and ducked out at the next stop. It was a long bike ride home. He was past tired.

You have the right not to be killed

Lights out. The mobile home was dark. Clark tried the front door. No luck. He went around the side and braced a sliding glass door. He got in. According to the prosecution, Sessoms and Wilson followed.

Surprise: Sheriff was there. He wore pajamas. “Goddamn,” Sessoms told Wilson, according to the Supreme Court briefing. “This motherfucker ain’t supposed to be here.”

The 68-year-old pastor asked his intruders if they were going to kill him. Sessoms promised they wouldn’t.

Clark handed Sessoms the keys to Sheriff’s Lincoln Town Car. They would take that and a GMC pickup truck, though that wasn’t part of the plan.

Clark bound Sheriff’s hands and feet with telephone cords and grilled the pastor. Where’s the money? He put his hands around the pastor’s neck and squeezed.

The phone rang. A woman left a message on the answering machine, something about pastries.

Clark moved to the front room and rummaged for money. He told Sessoms and Wilson to be on the lookout for nosy neighbors. Sessoms confronted Wilson in the kitchen: This wasn’t the plan.

Terrible sounds came from the bedroom. Sessoms looked inside. He saw Clark wielding a long knife. He saw it go in Sheriff’s chest, back, arm and neck. Sheriff screamed and gasped and twisted. Clark spoke as he stabbed: “Why did you do it to me?”

Pillowcases were filled with a few hundred bucks, jewelry and paperwork. Clark swiped the dead man’s Bible. Sessoms did a dazed drive in the dead man’s car. He dropped Wilson off at work, and picked up his share from Clark. He drove home. The dead man’s car sat outside his parents’ house. He got back in and drove it to Greenhaven. He left the Town Car on the side of the road with the keys in the door. He prayed someone would steal it.

Instead, police found it. They dusted it for prints and found Sessoms’ on contents inside the glove box. They found Clark and Wilson in Sacramento. They found Sessoms 1,600 miles away.

While this is the account that grew out of a compromised interrogation, Sessoms maintains that he wasn’t even in the state when Sheriff’s home was invaded.

He said he learned about the crime when Wilson called him in Oklahoma, and that he offered his friend a place to stay until things cooled down. Sessoms said he told the detectives that in the box, but that they wouldn’t hear it. They said they already knew that he was there and that he didn’t kill anyone.

Sessoms said the detectives peppered him with questions. They jumped to different points in the time line. What about this? What about that? They didn’t take his statement so much as lead him where they wanted him to go.

Sessoms said yes and no. He affirmed details. The cops wrote it up. He looked guilty.

You have the right to die in prison

The killer and his two accomplices faced the same punishment for Sheriff’s brutal death.

Sessoms and Wilson, who learned they lived on the same street years after middle school, were going to be tried together.

In September 2001, Wilson, who initially told police he only introduced Sessoms to Clark and didn’t participate in the crime, pleaded guilty to murder in exchange for the dismissal of felony robbery and burglary charges. He’s currently serving a 15-year-to-life sentence at a state prison in Solano County. A parole date came and went in 2013.

Sessoms was offered the same deal as Wilson, but refused it and went to trial. His court-appointed public defender tried to suppress his coerced statement to police. But when the judge denied the motion, the confession became the cornerstone of the prosecution’s case.

An appellate court later wrote that Sessoms’ statement proved that he knew about the planned burglary and went along, “expecting to rob the victim while he wasn’t home.”

The remaining evidence against Sessoms was weak. Sheriff’s neighbors spotted two short, stout men outside the mobile home, and saw two cars peel out of the area. Sessoms was tall and athletically built. The neighbors didn’t see a third man. There were his fingerprints in Sheriff’s car and two unreliable teenage witnesses who lived in the same house as Clark and Wilson; one said she saw Sessoms and his brother in the murder victim’s car. Sessoms’ brother was in prison at the time.

Sessoms said he later told his public defender the same thing he told Woods and Keller: He wasn’t there. Sessoms said he got the same response.

“He didn’t believe my innocence at all,” Sessoms said.

Because of the byzantine way the legal system operates, Sessoms’ version of events would be scrubbed from what happened next.

A jury found Sessoms guilty on all counts in May 2001. He was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole—the same punishment as Clark, who told the jury during his trial that he stabbed Sheriff 24 times in a fit of rage.

California lawmakers last year made it harder to convict accomplices for murders they didn’t actually commit. Senate Bill 1437 limits what’s known as the felony-murder rule, which essentially says that if a felony results in someone’s death, the actual killer and any co-conspirators are equally responsible.

The new law restricts the rule to major participants in felony crimes resulting in murder, as well as those who directly aided the killing. That nuance didn’t exist during Sessoms’ trial.

While behind bars, Sessoms focused on the ill-gotten confession. He appealed for a new trial and was denied. He appealed the denial to the California Court of Appeal and was denied again.

He thought back to this one exercise he participated in back in juvi. The boys were asked to imagine what they would be like in prison. Some fronted. They’d be hard. No they wouldn’t, said the man running the exercise. Look at me, he said. Sessoms thought he looked like a cool professor, smart and put together, holding their attention without pandering for it.

I did 11 years in prison, the cool professor said. Sessoms thought no way. It left an impression.

Inmate Sessoms became a habitual resident of the prison library. He studied law books and his case file. He pored over police reports, interview transcripts, trial transcripts. He scrutinized for inconsistencies and cross-referenced legal precedents. Thirteen points shy of his GED, he studied like he was preparing for the bar exam.

He tried to avert prison drama. At High Desert State Prison in Susanville and then California State Prison in Folsom, Sessoms avoided cliques and made friends with the prison librarians. Sometimes they sent case files to his cell so he could keep cramming.

He printed out a blank legal template and carefully printed onto it. He violated a cardinal principle, the one that says only a fool has himself for a lawyer. He represented himself and filed a writ alleging habeas corpus, or unlawful detention.

Less than a decade earlier, President Bill Clinton burnished his tough-on-crime credentials by making habeas petitions tougher for federal courts to grant. The federal courts can’t intervene when state laws have been violated.

“If it’s not a federal issue, they can’t handle it,” explained Eric Weaver, a Bay Area attorney. “That’s why there’s that slang, ’Make a federal case out of it.’ Because that’s so hard to do.”

The eye of the needle had gotten smaller. Somehow Sessoms threaded it.

You have the right to appeal again and again

Someone in the federal appeals court for the Eastern District of California flagged Sessoms’ petition as having merit. That got it assigned to the federal public defender’s office, which contracted it out to Weaver. He stayed with the case for the next 10 years.

“Once I got appointed, I was in it until the end,” he said.

Weaver and Sessoms hit numerous setbacks before they hit pay dirt. A magistrate judge recommended denying the petition. A district court listened. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the denial in a 2-1 ruling.

Weaver wrote his client a letter apologizing for striking out. Sessoms wrote back that the glass was half full. The one dissenting judge was his first legal victory.

“He stayed optimistic,” Weaver said.

The next move was to petition for what’s called an en banc hearing before the Ninth Circuit. Weaver made his case before 11 judges. They broke 6-5—in Sessoms’ favor. Judge Betty Fletcher wrote the majority opinion concluding that the state court’s decision was an unreasonable application of federal law.

The California Attorney General’s Office, under current presidential candidate Kamala Harris, argued to keep Sessoms in prison. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed Fletcher and kicked the case back to the Ninth Circuit.

By this time Fletcher had died and been replaced by Judge M. Margaret McKeown, who wrote the majority opinion in another 6-5 nail-biter for Sessoms. The circuit judge didn’t hold back. She excoriated Sacramento detectives for violating the “clear bright-line rule” that Miranda sets and blamed the state court for “allowing the detectives to play games” with Sessoms’ request.

“The only reasonable interpretation of ’give me a lawyer’ is that Sessoms was asking for a lawyer,” McKeown wrote. “What more was Sessoms required to say? Was he obligated to repeat the obvious—’give me a lawyer’—another time? It is no more reasonable to demand grammatical precision from a suspect in custody than it is to strip the officers of all common sense and understanding.”

McKeown also portrayed Sessoms—“a naïve and relatively uneducated nineteen-year-old”—as a poster boy for Miranda’s protections. Like the original ruling said 40 years earlier, Sessoms had also been “swept from familiar surroundings into police custody, surrounded by antagonistic forces, and subjected to the techniques of persuasion.” And when Sessoms “deferentially” requested the presence of an attorney, the judge wrote, “The detectives instead pretended that Sessoms had never raised the issue of a lawyer in the first place.”

Though the decision was closely divided, two of the dissenting judges sounded glad to be on the losing end in their written opinions.

Former Ninth Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski, who left the court in 2017 amid sexual misconduct allegations, wrote that the state courts “failed Sessoms.”

“[I]t’s just as well that our view doesn’t command a majority,” he wrote. “If the State of California can’t convict and sentence Sessoms without sharp police tactics, it doesn’t deserve to keep him behind bars for the rest of his life.”

Following the Ninth Circuit decision in 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Harris’ request to intervene once again. Sessoms’ conviction was vacated. He was sent to Sacramento County jail and the district attorney’s office was given new orders: Either retry Sessoms or cut him loose.

Sessoms spent two years waiting for that decision. Without Weaver to represent him, he said, a court-appointed attorney persuaded him to waive his right to a speedy trial.

“And the next thing you know, years go by,” Sessoms said.

The Sacramento County district attorney’s office said its Justice Training and Integrity Unit reviewed his case with higher-ups. “It is important to note at no time did Mr. Sessoms make a claim of ’factual innocence’ and therefore that issue is not discussed in the appellate history,” the office said in a written statement.

The office said it decided to retry Sessoms, though it would have to do so without his statement to investigators and by relying on the 20-year-old memories of a couple of compromised witnesses. But the process would drag on for months, perhaps years. Sessoms didn’t want to wait, or roll the dice.

The DA’s office extended an offer: Plead no contest to manslaughter and burglary and they’d call it time served. Sessoms took it.

“I didn’t want to take the damn deal because I didn’t do anything,” he said. “I didn’t have an advocate.”

The Justice Training and Integrity Unit formed in 2013 to examine claims of prosecutorial misconduct and wrongful conviction. In its statement to SN&R, the DA’s office said the unit has reviewed approximately 50 convictions and agreed to conduct DNA testing in at least one case, but hasn’t found any convictions that merit overturning.

It might not be looking hard enough.

The Northern California chapter of the Innocence Project, a nonprofit clinical program at the Santa Clara University School of Law, has successfully challenged more than two-dozen wrongful convictions since 2001, freeing 26 people who lost a total of 337 years to unjust imprisonment.

The exonerated include Zavion Johnson of Sacramento County, who was wrongfully convicted in 2002 of killing his 4-month-old daughter due to false medical expert testimony. Johnson, whose daughter slipped from his hands during a bath and struck her head on the tub, was released on December 2017. The DA’s office dropped all charges against him the following month.

The NorCal Innocence Project is working cases in 18 counties.

You have the right to be free

Sessoms had his hands full. He stiff-armed the coffeehouse door and hipchecked in the baby stroller. His 3-month-old son, Tio Jr., slept. Tio Sr. sighed in relief.

Sessoms pulled dad duty. His wife had gone back to work. Sessoms showed a picture of her on his phone and grinned ear to ear. He’d known her since they were kids. They said their vows one year to the day Sessoms got out of jail on Oct. 5, 2017.

“You never forget the day you get out from a situation like this,” he said.

Since he’s been out, Sessoms has tried to be the advocate he needed as a young man. He has a YouTube channel where he breaks down the legal process and has been on something of a criminal justice reform tour. He has linked up with the Anti-Recidivism Coalition and California Families United 4 Justice, meeting civil rights luminaries in the process, including activist Cornel West and actor Danny Glover.

He also wrote another lawsuit, this one while stewing in county jail. This one alleging the cops never had a proper warrant to arrest him in the first place. The city of Sacramento declined to comment.

His current attorney, former Sacramento County prosecutor Dominick R. Welch, said that even though his client pleaded to manslaughter, the city will have to pay Sessoms for the years that a vacated murder conviction stole from him.

“He spent 18 years in prison. He’s going to get paid for 16 of them,” Welch told SN&R.

Sessoms may be free, but he isn’t done trying to clear his name. A manslaughter conviction is standing in the way of his next chapter: He said he wants to become a criminal defense attorney, the kind of lawyer he asked for two decades ago.

“I know the law based on studying it all those years in a cage,” Sessoms said.

Now he wants to try practicing it out of a cage.

Be the first to comment on "A grisly murder. An illegal confession. A 20-year fight to be free."