How will people look back on art during the coronavirus?

A crowd of sickly pale figures is gathered in a brick courtyard: a young boy on the verge of vomiting, a woman wearing a mask, a man wiping blood from his nose, a man with grey skin collapsing in the middle of the crowd.

The scene is from “Epidemic” by Oakland artist Guy Colwell, made in 2009 in the midst of the H1N1 flu outbreak. The painting is a part of the Crocker Art Museum collection, and is eerily reminiscent of the current COVID-19 pandemic.

“He saw this coming,” said Scott Shields, lead curator at Crocker. “I talked to him about the painting before people were worried about coronavirus, and he said, ‘You need to make sure my painting is up, because this is coming, and it’s going to hit hard.’”

Colwell wasn’t the first artist to create work about a fatal pandemic. In 1919, Edvard Munch painted “Self Portrait with the Spanish Flu,” and in 1562, Pieter Bruegel the Elder painted “The Triumph of Death” about the Black Plague.

“Artists are always responding to what’s around them, and I have no doubt that there’s going to be a lot of artworks that come out of this experience,” Shields said. “How that will happen will probably range from everything from pure abstraction to really highly realistic representations of people with masks.”

Art has consistently been linked to big cultural moments in human history, and the coronavirus pandemic is no exception. So how are Sacramento artists contending with the current moment?

For Julian Sander (also known as Julian Sandpaper), it has meant channeling his feelings of anxiety into a message of responsibility, with a hint of rebellion.

“I’m not a person who gets scared that often, but man, it was really crazy those first couple of nights,” he said. “Was I really going to not be able to leave my house? What’s going to happen tomorrow? I had no idea.”

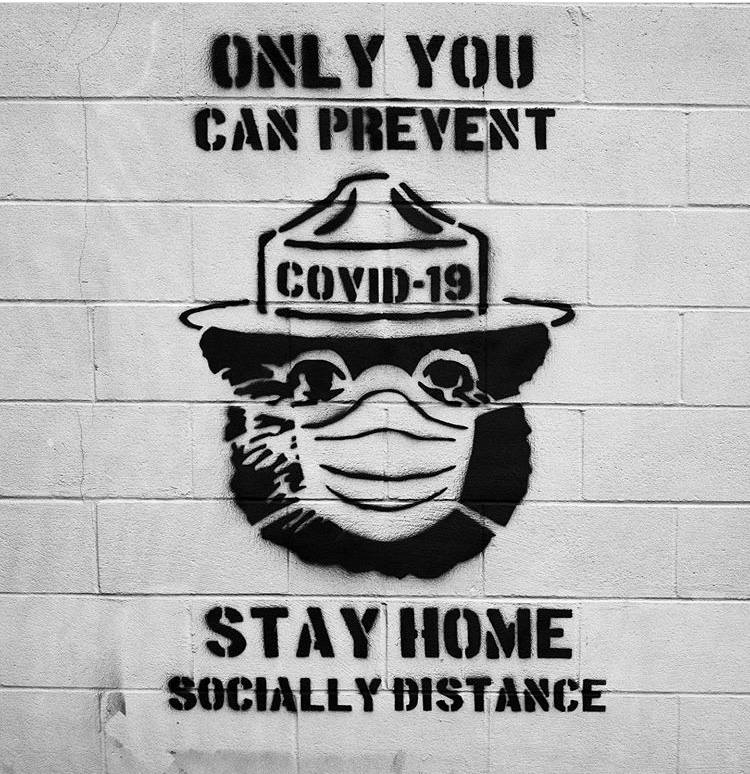

Sander created a stencil of Smokey the Bear with the caption, “Only you can prevent Covid-19, Stay home, Socially distance,” and began to use temporary chalk-based spray paint to spread his message across Sacramento.

“Some people have called me out on it, like, ‘Well, what’s the point when you’re only gonna see it when you’re out, and we know that you left your house to do this?’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah, I know.’ I don’t have all the answers,” Sander said.

Because it is made using chalk spray paint, the work will soon fade and disappear, but Sander doesn’t mind his art being washed away.

“I think it’d be great for me to forget that, ’cause to be honest a lot of what I was doing, it was fueled out of fear,” he said.

Responding to coronavirus through art isn’t always so direct.

Andres Alvarez’s work has been guided by his subjective feelings and by how artists in the past have dealt with similar moments.

“I’m thinking, ‘OK, let’s embrace this moment, ’cause this is just another facet of history, right? Another virus has taken over our timeline, and so what can we do about it?’” Alvarez said.

Rather than just documenting the moment, Alvarez began creating charcoal drawings based on photographs sent to him by people who were staying at home. He imbues the portraits with his own subjective reflections—using dark shadows, obscured faces and distorted perspective, the uncertainty of the moment is laid bare.

“These feelings of uncertainty aren’t seen as a way of anxiety, it becomes more of a way of a possibility,” Alvarez said. “There’s a lot of feelings coming about right now—we need to transmit this, to create something.”

In addition to the charcoal drawings, Alvarez began to make photographic portraits of fellow artists in their homes.

“I was seeing images on Instagram about people being photographed at home through the window, but they were very much snapshots,” Alvarez said. “I wanted to do something that dove a little deeper–this idea of the window and how it’s been used throughout history. The windows looks out, but it’s also a way you look in.”

Alvarez says he doesn’t think much about how people in the future will look back on his work.

“The drive is to just do it and to create. Whether or not people in the future will look at it, well, that’ll just come out on its own if it does,” Alvarez said.

According to Shields, we won’t know what will end up in the history books for years, and maybe decades to come.

“How this will manifest itself in a big picture way—what is the major theme that’s going to come out— we won’t know for probably a couple of decades,” Shields said. “You have to look back at it to see if something will emerge from it, that we don’t know when you’re right in the middle of it.”

Be the first to comment on "A brush with history"