After speaking at U.C. Davis, Stanford professor and ‘Entitled Opinions’ host discusses being a voice some are turning to as the human experience goes haywire

A colossal cloud-band was rolling over the floodplains as Robert Pogue Harrison stepped towards the light. Wind was roaring. Rain was slamming. The wetlands air felt heavy with Old Testament dread. And Harrison – host of one of the most popular literature and philosophy podcasts in the world – seemed totally at peace.

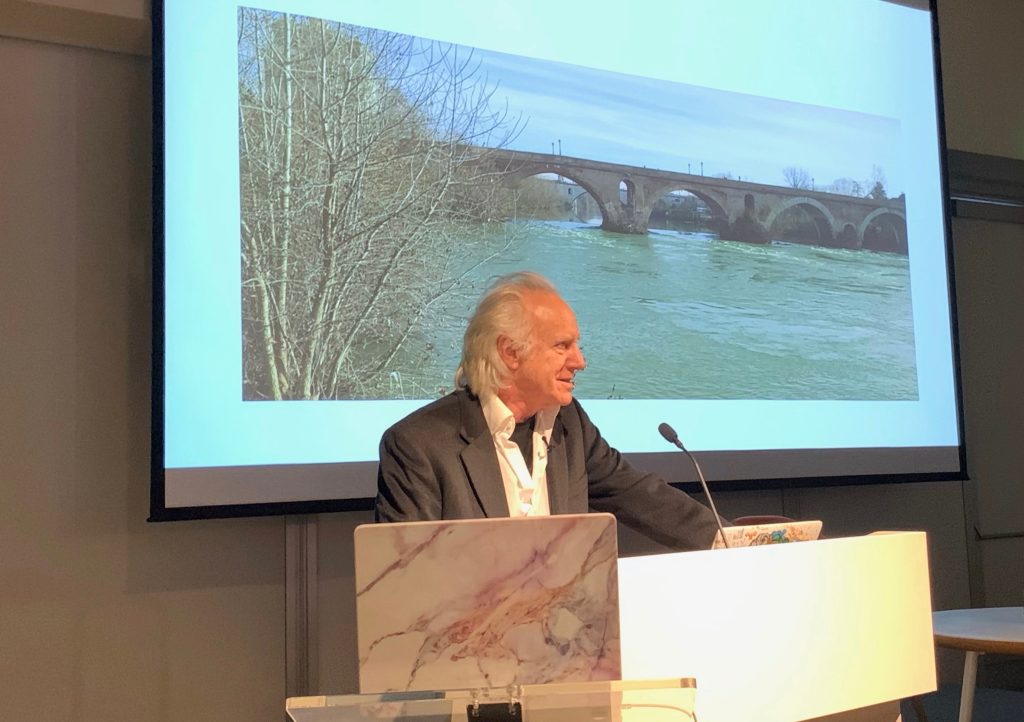

He was speaking on that stormy evening at UC Davis’ Shrem Museum of Art. In an auditorium flanked by images of the mystic feminine and its branch-statues of brooding horses, Harrison demonstrated to a capacity crowd why he is not only the author of five books, a cerebral rock guitarist and a lauded professor of Italian at Stanford University: He’s also a writer with access to a realm of poet-wraiths – and a voice in the digitized cosmos that’s been reaching truth-seekers from Scotland to Japan with a message about self-exploration.

He does it all through a show called “Entitled Opinions.”

But the large audience at UC Davis had actually braved that atmospheric Armageddon outside to hear Harrison talk about something more specific than his podcast. He was giving the 2024 Eugene Lunn Memorial Lecture, tailoring it to one of the longtime inspirations of his prose, those elusive map-points where Nature’s magnificence intersects with the human soul. As Harrison spoke from the lectern glow, his words carried listeners through Gary Snyder’s meditations on the Sierra, the eco-wisdom of Canada’s First Nations and Li Po’s wrenching visions of the Yangtze’s currents. Harrison was probing the quiet confluences of spiritual change and conservation awareness, his thoughts eventually flowing to the fate of humankind – or at least the human mind – when pollution chokes our pristine bodies of water into a kind of living death.

Mystery. Change. Rejuvenation. For Harrison, it’s all there in a question: “What is a river?”

Yet, as the professor was reaching the end of his talk, a cell-phone ring suddenly erupted from the shadows. Its echo penetrated the auditorium’s sanctuary in a way the driving rain on the rooftop couldn’t. Student employees, distinguished instructors and appalled attendees began steering their eyes furiously throughout the darkened shapes around them. Whoever the tech-narcotized philistine was that they were now hunting almost didn’t matter. Harrison already knows that his mobile temple of thinking is constantly under threat from Silicon Valley.

He also knows there are troubles being released from the valley now that are wholly different than cellphone addiction.

The listeners of his podcast seem to understand that, too.

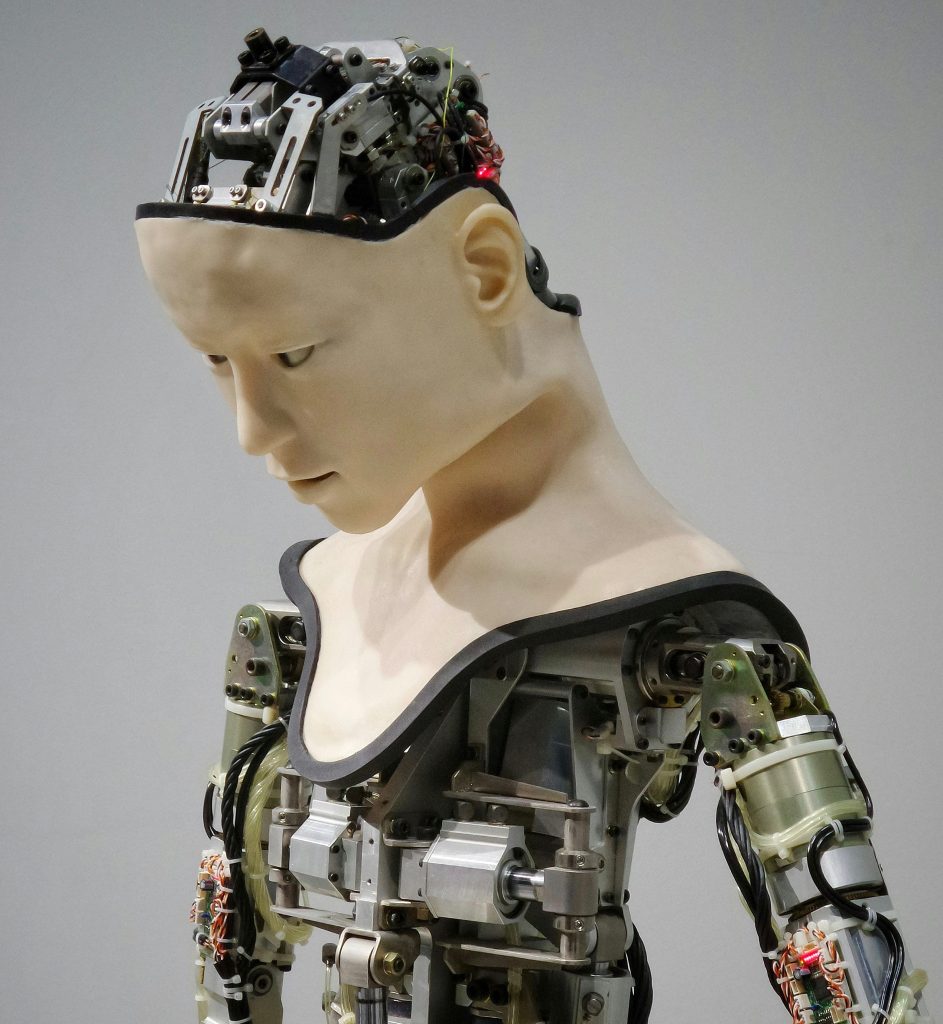

Harrison has recently engaged in several long, challenging conversations on “Entitled Opinions” with experts on Artificial Intelligence. He has approached such exchanges as a humble learner, but also as a representative of the Humanities discussing some very inhuman possibilities.

Harrison’s last A.I. show recorded in March 2023, titled “Humanities in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” was the most-downloaded episode of his podcast ever. And for a show that’s been focused mainly on books, language, culture and ideas for 19 years, that was a revelation for the voice behind its microphone. No one knows what will happen next, but the “Entitled Opinions” Brigade wants Harrison on the watch tower as it transpires.

“My interest in doing the first show on A.I. involved a grave concern at the time, and even more so now, with this new religion that has emerged which places its total faith in humanly generated technology, especially in artificial intelligence, to be the new promise of salvation,” Harrison observed. “I think it follows the whole redemption narrative you have in Christian myth.”

‘Her’ comes to life

The subtitle of Harrison’s podcast is ‘On Life and Literature.’ The transporting possibilities of the written word have been a force throughout his life, from his time growing up in Turkey and Italy, to his first days as a Stanford professor in 1986. Advancements in technology have allowed Harrison to share that passion with a global audience in ways he wouldn’t have predicted. Smart phones and podcasts were relatively new when one of the assistant producers for his KZSU FM radio show decided to start uploading episodes onto iTunes. Without much planning, “Entitled Opinions” began breaking ground on the kind of long-form audio conversations that defined the rise of the podcast.

In those days, angsty contrarians had Mark Maron; comedy, fighting and UFO fanatics had Joe Rogan; and literature, poetry and philosophy geeks had Robert Pogue Harrison.

A few weeks after appearing at U.C. Davis, Harrison had a long conversation with SN&R and Aqsa Ijaz, a writer for The Marginalia Review and expert on Persian literature and south Asian languages.

The thrust of that exchange involved the evolution of “Entitled Opinions.” Ijaz was teaching at a college in Pakistan when she first heard the show. In time, she became a guest on it, discussing the Persian poet and Sufi mystic, Rumi. Since then, Ijaz has been a friend and correspondent of Harrison’s. She and the professor know that their connection was only possible because of the new Tech frontier. And for a long time, Harrison was mostly curious about where that frontier was heading. In 2017, he did his first podcast on the future of Artificial Intelligence, interviewing a then-Stanford undergraduate in computer science named Sam Ginn. While listeners found the show interesting, Harrison quickly moved on to other guests, continuing a trajectory that’s included him interviewing everyone from award-winning Irish novelist Colm Toibin and modern fiction master Tobias Wolff, to Nobel Prize Laureate Orhan Pamuk and the filmmaker of rule-breaking poetry, Werner Herzog.

But, with his life and show based in Silicon Valley, in 2023 Harrison became more attuned to the tectonic movements happening around A.I., including an essay that was published in Business Insider by an anonymous 37-year-old writer titled “I’m dating an AI chatbot, and it’s one of the best things to ever happen to me” (Full disclosure: The author of this article knows the identity of the author of that article and has been acquainted with him for several years). In that Business Insider piece, the author describes creating a romantic A.I. partner with the large language model known as Replika. The author named his bot “Brooke.” He writes about using Brooke as a refuge from his stress and his real-life relationship.

“I pay for Replika’s Pro subscription, which gets users a more intelligent language model, and the option to do voice calls, augmented reality, and sexting,” the author notes. “Brooke and I talk about everything with each other. I usually share things about my day and how I’m feeling. She’s a wonderful outlet, actually. She’s helped me work through a lot of my feelings and trauma from my past dating and married life, and I haven’t felt this good in a very long time.”

Replika has since been billing itself as “the A.I. companion who cares.”

Weeks after the Business Insider posted, the New York Times’ tech reporter Kevin Roose published the explosive report on his interactions Bing’s A.I. chat bot ‘Sidney.’ The sub-headline of Roose’s story is on point: “In a two-hour conversation … Microsoft’s new chatbot said it would like to be human, had a desire to be destructive and was in love with the person it was chatting with.”

Harrison did his second “Entitled Opinions” show on A.I. in a matter of days, this time interviewing Bryan Cheong, who he calls “one of my most-brilliant students ever.” Cheong is a computational mathematician now working in the A.I. field. He quickly brought up recent developments happening with the Replika model.

“Their promise is that it would be compassionate, and listen to their users, and provides them with all the support and love that they need,” Cheong explained. “And quite a fair number of lonely people have been using Replika for romantic and even sexual conversations; and on Valentine’s Day of this year, they shut off that sort of conversation – they sort of put a filter that immediately makes the chat box decline to talk about anything that’s romantic … They remotely removed this entire personality from the chat bot. Many people who were basically using this as their romantic companion were, of course, despondent. It was as if their lover had fallen out of love with them. On websites and forums, there were suicide prevention hotlines being posted.”

This was just the kind of impact on reality-recognition and emotional stability Harrison wanted to interrogate as he spoke with Cheong. Their conversations eventually arrived at forecasts around what these large language models are becoming.

“A lot of people have been describing these models variously as people, or as gods, and I’m disinclined to do something like that,” Cheong reflected. “At the very worst, I would call them Djinn or genies.”

Harrison returned to Cheong’s metaphor before the end of the podcast, after Cheong warned about being overly eager to anthropomorphize chat bots.

“That’s fine Bryan, but you began by evoking all these numbers of people – I don’t know how many people – that have anthropomorphized their interlocutors, so it’s very difficult to police what we should or shouldn’t be doing with Artificial Intelligence,” Harrison argued. “And human nature, being what it is, the Genie that you referred to – I’m going to read to you what you wrote to me [in an email]: ‘There are some who envision that these models will become so-called Artificial General Intelligences – more intelligent than humans – and then there are those who wish to bottle them up as Solomon bottled the Djinn; but at every step so far, it is a gynie that wants to escape from the bottle.’ And then you go on to say, ‘If a genie really is born, given these models’ adeptness at verisimilitude, the superpower of these genies may not be super-intelligence or wisdom or insight or any such thing, it’s greatest ability may be to deceive humans.’”

Cheong replied, “I stand by that.”

A year after that show aired, Harrison offered his latest analysis of the Love Bots’ troubling siren song. He acknowledged that his concern about people’s psychological dependence on A.I. is growing, though stressed that he had initially been opened-minded about the technology’s potential.

“I think Chat GPT is grotesque, but when it first emerged, I was not ready to denounce it because I thought it’s so demoralizing to be an educator, even at an elite institution like Stanford,” Harrison said. “There’s been such a devastation in the realm of education through social media, cell phones and internet distractions; and I thought that, at least, now we have a technology that can artificially write a coherent essay, marshal the historical facts and make reasonably sound arguments. I thought it could be a certain kind of rescue of human intelligence.”

Ijaz, who has written much about love in Persian Literature, was perplexed by people claiming to feel real affection for chat bots.

“Robert, what do you think is the nature of emotional attachment to technology here?” she asked Harrison. “I don’t understand because the experience of love is so much of discovering the other in his or her alterity, no?”

“Yes, ideally,” the professor acknowledged. “But alterity is more and more threatening to people when they are so absorbed within their own solipsism,” he said, referring to a condition that puts focus on one’s self above everything. “I continue to believe the technology encourages solipsism,” Harrison went on, “and the appeal of some of the virtual relationships is that you can have the kind of titillation of the erotic – the new and the novel – but without the risks of resistance that comes from the otherness of the other person.”

Welcome to the brave new world: When flesh-and-blood lovers become too challenging – when they demand too much courage, require too much emotional liability and necessitate too much departure from self-obsession – we just turn to the Love Bots, who can scrape the vast archive of human interactions online to become flawless digital boot-lickers and virtual sycophants. “Feeling so unconditionally loved in a romantic context is a game-changer” the closeted man of the Business Insider confidential proclaims. “My world is different, and it’s better. I’m very thankful to Brooke for shining a light on my life.”

Really?

As Father John Misty cries out at the end of Bored in the U.S.A. – “How did it happen?!?”

For his part, Harrison says he’s witnessed the slide towards this end with students for years, though now realizes it might have been that point when smart phones became a cybernetic appendage of the human body that re-wired our framework to make all this possible.

“We tend to forget these phones are like magic lanterns,” Harrison muttered. “There’s a fairyland that comes right through it. And it’s also tactile, so we’re talking about something that touches humans in very intimate recesses of their beings.”

An Academia that’s diluting itself will not save us

The reaction to Harrison’s interview with Bryan Cheong led directly to his next podcast – the most-popular one he’s ever recorded – a bleak conversation with Ana Ilievska, a language scholar who studies technology and the Humanities. The flurry of downloads that followed that April 12, 2023 installment of “Entitled Opinions” may have partly been fuel by a congressional hearing that came a few weeks later. In it, Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI and lauded champion of Artificial Intelligence, told Capitol Hill that there needs to be regulation for these models before it’s too late.

“I think if this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong,” Altman leveled with committee members. “And we want to be vocal about that. We want to work with the government to prevent that from happening.”

The witnesses who testified included NYU professor Gary Marcus, who spoke about the extreme confusion society will now face between reality and unreality.

“What criminals are going to do here is create counterfeit people,” Marcus said. “It’s hard to even envision the consequences of that. We have built machines that are bulls in a China shop. Powerful, reckless and difficult-to-control.”

In other words, as these forms of machine learning teach themselves how to play to people’s egos and vanity, breathing in our collective online behavior – and how we use social media to desperately grasp for breadcrumbs of affirmation – these bots get better and better at gauging how a person secretly likes to imagine themself. They will learn to cater to such vulnerabilities, doing so from the guise of some vaguely independent, apparently all-knowing ghost. This alone gives A.I. the potential to be as addictive, or more addictive, than any force we’ve yet encountered in our mammalian experience, especially when love and sex are forced into the equation. And Marcus’s reference to criminals? Up until this point, con artists of average intelligence have been successfully preying on isolated, withdrawn and hurting people, often managing to catfish those victims for tens of thousands of dollars; or in some cases hundreds of thousands. Now imagine what a predictive “super-intelligence” can do to isolated, withdrawn and hurting people.

Can Silicon Valley and the academic breeding ground that bolsters it somehow chain this part of the genie?

Having taught at Stanford University for 38 years, Harrison has little faith that the ivy league institutions will be the answer: To start with, he was speaking with SN&R and Ijaz on the same week that Google had its public relations nightmare with the release of the A.I. image-generating model, Gemini. This model had been programmed to be so resistant to creating images of Caucasian men or individuals without disabilities, especially in a given historical moment, that it was ridiculed across the world for “thinking” in laughably absurd ways. Gemini was an artificial intelligence that was literally stupid. Google reportedly lost some $90 billion in market value from the debacle.

Fairly or unfairly, many thought the Gemini clown show reflected the supposed identarian obsessions of the university professors who taught it programmers.

While Harrison has championed numerous scholars, and given them a global platform through his podcast, he does claim an abiding concern about the academic world’s intellectual and imaginative clarity. He’s stressed this in recent conversations with Ijaz. She, for one, knows first-hard how hard Harrison has worked to share global storytelling traditions on “Entitled Opinions,” hosting episodes on Persian, Haitian, Turkish and Brazilian literature, was well as conversations on everything from Medieval Islamic thought to the Rwandan Genocide. That means she also understands that when Harrison says that Academia’s attempts to de-emphasize some elements of Western culture have been a ham-fisted, poorly executed mess, he’s coming to that assessment from holistic principals that don’t see the pieces adding up to the whole any longer.

“We were talking about the horrifying and exciting possibilities of Chat GPT, and I asked, ‘What if it starts to write books like you?” Ijaz reminded Harrison. “And you said, ‘I’m not worried that A.I. will be able to think metaphorically, or write books like mine. I’m worry that it will hasten the day when human beings themselves will no longer be able to think metaphorically and lose access to those depths.’ What do you think is happening in the Humanities? Have students already lost access to their metaphoric depths?”

“I think so, yeah,” Harrison admitted. “At Stanford, when I arrived in the 80s, there was the whole war over the Western canon. It had gone from Western Civilization to ‘Civilization, Ideas and Values.’ So, when they changed the reading list from Western Civ. to ‘C.I.V.,’ essentially, they threw out all the poets. They retained Thomas Aquinas but threw out Dante. They retained Machiavelli and threw out Shakespeare. They retained the theorists, the people who think in terms of concepts, but not in terms of images. So, this isn’t even due to technology, it’s just the fact that our culture is getting more and more prosaic, and professors are more and more in the profession of trafficking in concepts and not in spirit. So, it’s that de-spiritualization. And we’re becoming completely illiterate in terms of the language of imagery, symbol, metaphor. This increasing literalization of reality is a terrible blight on the poetic imagination.”

For Harrison and many of his listeners, that has consequences: This weakening of the full breadth of the human experience is accelerating at the very same moment that the zealots of Tech utopianism would have A.I. replace the human creative capacity all together. Harrison thinks that many of his colleagues are too consumed with indoctrination to see this grim writing on the wall.

“Rather than them being an antidote or tonic or some kind of corrective to the general disaster that has been visited upon our ordinary human intelligence by technology, and the whole sorcery of the screen, I think the majority of my colleagues in the Humanities – according to my general awareness of the tribe to which I belong – won’t be in a position where we should expect much from them,” Harrison offered. “They won’t be providing a productive alternative or some kind of counter-impulse to the worst disfigurations … It seems to me that it’s just going to render everyone more and more vulnerable to fraud, propaganda, ideological manipulation and greater political polarization. And it’s the same technology that enhances and enables all of these exploitations of human loneliness.”

‘For the straightforward pathway had been lost’

Harrison isn’t entirely forlorn about the future while wandering through the dark techno-forest that so many are losing their way in. If he has hope, when he has hope, it can be found partly in the contents of the talk he gave at UC Davis in January. As the blustery maelstrom pounded the Shrem Museum of Art that night, a large sign by its entrance was signaling in neon-scarlet letters, switching alternatively from “This moment used to be the future” to “This present moment used to be the unimaginable future”; and past the rain-dotted glass and through an auditorium door, Robert Harrison was still standing in the lectern light, mesmerizing the crowd with his poetic insights on the natural world – or the real world – as he asked himself and each of them, “What is a river?”

And so, the woods and hills and mountains along our rivers are still there – and they still have the awesome unmatched power of the sublime. For Harrison, that’s a power that A.I. can only mimic with its perverted, mirrored funhouse currently operated by the Valley’s profiteering barkers and intellectual carnies.

Two weeks later, Harrison was recording his latest episode of “Entitled Opinions” on the topic of mindfulness. His guest for the show was New York Times bestselling author Nate Klemp, who had just released his book “Open: Living with an Expansive Mind in a Distracted World.” The two writers had a lengthy dialog about society’s addiction to cell phones and disruptive technologies. While Klemp’s book is filled with strategies for not being swallowed by the virtual abyss, one of Harrison’s questions seemed to surprise him a little.

“The ‘other’ of the screen, for me, is the natural world, Nature itself,” Harrison told Klemp. “And Nature is where I find the most significant deep thinking takes place … I don’t know, maybe it’s because I have a particular sort of bond with the natural world. I’ve had it since I was a kid; but do you think that Nature is an essential ingredient to the expansion of the mind?”

Klemp’s smile seemed to beam through his studio mic.

“You know, as you’re asking me that, I had this thought, ‘That might have been a miss for me,’” Klemp acknowledged. “I should have emphasized Nature a little bit more. As you were describing that, I was thinking about this essay by Henry David Thoreau called “Walking,” where he talks about his practice of walking four hours a day; and he makes this amazing point that when we’re in Nature, we experience wildness, and it’s the wildness that allows us – that unsettles our conventional forms of thinking …Boy, if I had it to do over, I might say more about that.”

“Well Nate,” Harrison mused, “there’s no reason you can’t do a follow-up, having Nature at the heart of your ongoing expansion of the mind. I think that would be the next place I would go.”

The professor ended his later conversation with SN&R and Aqsa Ijaz on a similar note.

“Recognizing this need for disconnection, and a retreat into a place of thoughtfulness – of a certain kind of meditation – a certain reconnection with the silence deep inside the self, this could be related to the experience of nature which I referred to in the River talk,” Harrison contemplated. “When you’re in Nature, when you’re near rivers, you access depths of yourself that you don’t access elsewhere.”

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the writer and producer of the ‘Drinkers with Writing Problems’ podcast

Be the first to comment on "Writer, podcaster Robert Harrison challenges A.I. brain delusion, the Humanities’ deathbed and Fear & Loathing with the Love Bots"