By Casey Rafter

For over 20 years, Sacramento photographer Elle Jaye has been playing with light, water and laughter to capture electric images in her work. She’s taken photos for G.I.R.L.S Rock Sacramento and held sessions with local acts like Katie Knipp, The Gold Souls, Jessica Malone and Dear Darling. She has a fiery passion to capture drummers and their instruments, enchanting musicians like Karen Wulff, Questlove, Daru Jones, Corey Strange and Mike Johnson.

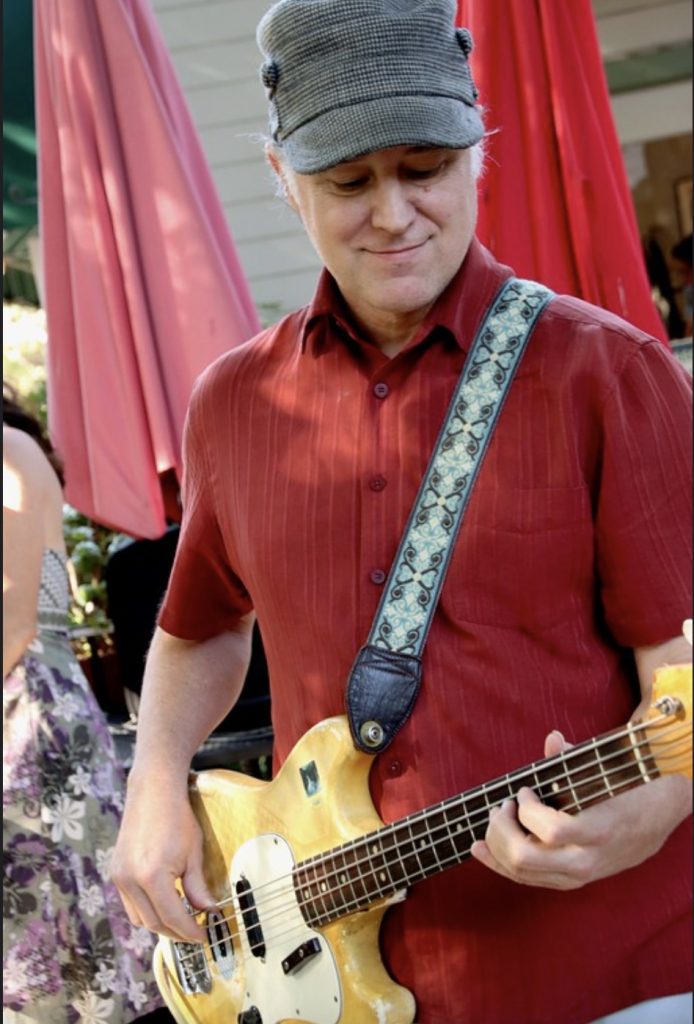

At 12 years old, Sacramento musician Gabe Nelson found a guitar in his mother’s closet. A trade from guitar to bass eventually saw him as the bassist for the band Cake, creating the familiar funkiness heard in the band’s most popular recordings before leaving the band in 2015. He’s also played with Anton Barbeau, The Mother Hips and has his own band, Bellygunner.

The two met for the first time at a creaky table in the living room of Nelson’s Sacramento home. The only connection they shared was in Katie Knipp, who Nelson played bass for in recent months.

Elle Jaye: Thinking about Sacramento as a community for musicians and artists. Do you feel a part of that community?

Gabe Nelson: Yes.

Jaye: That’s a great answer. 10 stars.

Nelson: Sure. I mean, I’ve been here a long time. I started performing in places at around the age of 15. I still do. All my friends are in the art world or the music world. Those are the people I know. I started making a living at it. And I’ve just kind of hung on to that. … How about you?

Jaye: That’s the majority of my community: Sacramento. I don’t live in Sacramento.

Nelson: Where do you live?

Jaye: I live in Shingle Springs, which is the middle of nowhere. There’s about a population of 1,400 people but most of my time is spent down here. Everybody’s like “Do you come down to Sac often?”” It’s a 40 minute drive. I’m down five times a week. Most of my clients are in the music and art world and I don’t have friends outside of that space very much. So Sacramento is me. Minus the residence part. …

Jaye: Does Sacramento register as part of your identity?

Nelson: Well, I definitely think so. When I was a kid, I lived in Orange County and we moved like all the time. I never had any roots. I never had any friends for very long. My parents got divorced and my mom moved up here and I came up here a few years later in eighth grade. She asked me, “Is there anything that you would like to request living here?” And I said, “I just want to go to one high school.” She made it so that I went to Sac High and I didn’t go to any other schools, because by that point I was just so tired of going to almost two schools a year.

Jaye: That’s hard for a kid.

Nelson: Socially, I think, you know. I’d be bonding with people then having to leave. I think that was a bit damaging. … I’ve kind of just lived my adult life that way, too. I don’t want to go anywhere. It’s been good for me, I think, to know someone for a decade.

Jaye: For me … I’ve always lived here, but I’m a wanderer. I have a little vagabond heart. But my roots are here. I was born in Citrus Heights. And I went to school there and I didn’t move out of the region until I was 22.

Sacramento does register as part of my identity, but I also feel like I am a little bit of everywhere. I have this heart that’s very — I belong everywhere and nowhere at once.

Nelson: How often do you take photos?

Jaye: I take photos every day. I have my camera on at least once a day.

Nelson: It almost seems basically like hunting. You got to find something to photograph. So you’re looking for something interesting.

Jaye: It’s kind of almost the opposite for me where things are asking to be photographed. Like everything is a little magical. Like in the morning, the way the sun falls in the trees, it’s like the fairies are there. I don’t necessarily believe in mythical beasts, but every little thing if you’re looking at it with the right light — which is really all photography is — is incredibly magical and wonderful and delightful. And if you look close enough, it gets even more interesting and fascinating and fun.

Nelson: Do you do macro?

Jaye: I do a lot of macro things. For work purposes, I really love macro when I’m looking at an instrument. I’ll take drums for example, because that’s my niche. I have a snare drum. The grain in the wood, or the difference in the block or the staves, where you can see the way the stain has fallen in between the pieces of wood. You flip it over and the snares and how weathered they are. If it’s a vintage snare and it hasn’t been played for a while, it’s going to have some oxidation. It’s going to be a little crusty. Could be rusted, could be just old. The stamp from the company of the snares. The way the snare bed is cut, back over the lugs. All the pieces. The throw off. I love interesting throw offs on snares. All of those are really beautiful when you get in really, really close and really, really deep on the macro level. If it’s a calf skin head, it’s gonna have the texture —

Nelson: Almost the sinuous —

Jaye: Yes, the fibers. Every piece of it is so beautiful. When you take a step back and you see the whole snare for what it is, it’s lovely. A sound engineer will look at it in a completely different way and be like, “OK, none of those lugs are tightened properly. That sounds terrible. The throw off is missing a thing. And for me, look at the patina! It’s a snare, but up close, it’s 17 pieces of art that live in like this little 5-by-14 piece.

I do drumset sessions, where I will take a drummer out and we’ll go to a random location that makes them happy or makes me happy. I set up all the studio gear and photograph the kit, I photograph them playing … all the little nuanced bits. I love the way lights fall on cymbals and the label on the underside. But they’re like “I need to go get a clean pair of sticks.” Don’t. Don’t get clean sticks, because I love seeing the snare digs on the side of the stick because that shows that you are an actual working musician and you’re doing the thing. The texture and the life that lives on the stick is just beautiful to me. I love the decay of use of something that has life and something that is being used for its purpose. I think that’s so lovely.

Nelson: I had this bass from — I guess I was 14 when I got it. … It was in the closet for a couple of years because it had gotten unplayable. I had played so many gigs with it. You just couldn’t play it anymore. I didn’t want to just leave it in the closet, I wanted it to be playable again. So I took it and had it all fixed up. It’s really nice now. It really plays well. It’s on all the Cake records and a lot of other records, too. It’s on a lot of Anton Barbeau’s stuff. All the recordings I’ve done over the years. It’s everywhere. I’m glad it’s fresh and I can play it again.

Jaye: Have you ever been moved by your own work?

Nelson: Oh, well, sure. Yeah, I mean music’s a performance art, but it’s an art before it’s a performance. I always work alone, so music is a very private thing for me. Performance of music — by that point, the music’s already changed to something else. By the time it’s being performed, I’ve replayed it maybe 200 times. I’m probably not actually moved by it anymore, I’m just doing it because I think it’s well constructed and it’s part of what I want to do. Music kinda wants to be performed. The initial side of the process is were you digging into yourself and you’re trying to pull something out? … That can be very emotional. …

You must go through this with photographs where you’re like, “I’m going to use this one that I have. I’m gonna give this to the world now.” There’s that bridge that you cross over. I have a ton of music that I probably wouldn’t play in front of people. Usually, the reason is it’s not good enough. If I feel like it’s good enough, it kind of crosses through a bridge and I decide, this is not really for me anymore, this is just for anybody who wants it. I think there’s phases of my life where I’m not going to perform anymore. Even if I never perform again, I would still write music every day at home, because that’s just part of my life.

Music sort of nags at you. It wants to be put out into the world for some reason. I don’t know if you feel that way about photographs or not, but it seems like you probably do.

Jaye: I mean art, creation needs to happen. I think creation aches for existence. I need to create something whether that’s a photograph, or it’s a meal for somebody or it’s facilitated by photography.

I write and I play music when I get a roadblock in my head or I get bored or I just can’t be in front of the computer anymore. I’ll turn around — because I’ve got my keyboard and I’ve got my guitars — play a little something. Creation is necessary for me. It doesn’t necessarily have to be the medium that I’ve chosen as a profession. …

Nelson: I think most people in the world, there’s not one moment in their life. Where they’re like, “I need to do this right? I need to write a song or I need to take a picture.” It’s hard for people like that to understand.

Jaye: I imagine somebody who’s in HR is like, “I need to get back in process W2s.” I could be wrong. I’ve never been an HR person, but if I’m not shooting for two or three days, I’m like, “The berry bush looks really, really good right now. That needs to be photographed.”

Nelson: Would you agree … that you have an urge to tell a story? To try to share the way you see the world?

Jaye: Possibly, yes. I think it’s the way I see the world. I’m gonna brag a little bit, because I think that my eyes process the world in a more beautiful way than a lot of people. There’s something about it. The light goes inside of my eyeballs and goes into my brain and it is glitter-rainbow-magic. I find so much lovely about the world where people are like, “Oh, it’s just a tree.” No, no. Look deeper at the tree. Look at the fruit that is producing the flowers.

If you look at all the little, beautiful, wonderful things — or if it’s just a person. We can pass judgment on any one person like, “He’s just a dude.” No. Stop for just a second. It’s not just a dude. That person is the combination of 40 years of experiences and hurts and love and loveliness and it shows in every bit of their canvas. Their eyes have all of the memories of the smiles that they’ve ever had. When I look through the world, I’m moved to tears by how fantastic things are. … Photography is a means to creating a space for people to see inside of my head.

If I can have an experience with somebody when I’m photographing and … have a conversation … I want to know who you are as a person. I want to know what you’ve been through. I want to know where your hope lies.

Have I ever been moved by my own work? Absolutely. It’s those moments: It’s the loveliness of seeing somebody’s demeanor change in a space where they may have been very timid and very self-conscious and very self-critical. Then they can look at a picture of themselves and say, “Oh my gosh, how did you get that?” Baby, you were there that whole time.

Nelson: Talk about collaborating with other people who do the same kind of thing that you do? Is it a competition or an opportunity or both? I don’t really collaborate. I used to. If someone else writes a song, I can easily jump in there and start contributing. I find that, if I write a song, I write all the parts. …

Jaye: When you have a voice in your head for a song … this is how this song wants to be played. It’s really hard to give that over to somebody else.

Nelson: Maybe if that collaborative person had enough time, but they don’t have the amount of time with my song that I do. I’ll write something and I’ll record it on my phone. Then when I’m in my car, I’m listening. I don’t really listen to other music, unless it’s for work. In my own private world of music, I’m daily reviewing notes and adding to them. I’m in the process. I’m working on 40 songs at a time. This one needs a bass line. This one needs more words or this one needs a harmony.

Jaye: And you have that all cataloged in your head. So when somebody else comes in, “I think we should do this.” No, that’s not what we’re doing for this one. How dare you talk about my child this way.

Nelson: It gets a little comfortable because I feel I’m having to reject their ideas … that doesn’t feel good to either one of us, so I tend to avoid that.

I was in Cake and I was recording with Cake. And I was pretty frustrated because everything is by committee. I just want to break free. I want to do what I want to do. So I decided to start recording at home. A friend (opened) up a club and was looking for bands to play. I didn’t have a band. He’s like, “Put one together.”

I had all the songs written and recorded and the arrangements were very worked out. I, suspecting that other people in the band want to be creative, have at times said, “I have this song. It’s not arranged. It’s just in its seedling form. Do you want to hear it?” Sometimes they’re like, “No, you just work it out. We’ll just play what you write.” I’ve had that reaction. I feel torn about it. I would like to collaborate. It just doesn’t seem to be that easy. It’s only easy if I’m working on somebody else’s stuff.

Jaye: Do you feel like you have had experiences where people have returned it and you’re like, “That’s the worst thing I’ve ever heard. Thanks for playing.” And then you have to reject their thing. And then they’ve been upset about it?

Nelson: Yeah.

Jaye: That would make you gun shy, I imagine.

Nelson: Yeah. On the other end of that, too, I mean, I have … been invited to record or compose with people and work on their stuff and they’ve said to me at the end of it, “it’s not quite what I’m looking for.” You have to be thick-skinned and go, “OK, I gave it my best shot. I don’t know what’s in your head.” It’s not easy for them to say that to me, they do. I’m glad they do when they do, because it’s not about me. It’s about getting that piece of music to be the ultimate piece of music that you want it to be. If you make compromises, you can’t make good art. You have to work towards a vision. Anything that gets in the way of that you have to knock it out of the way.

Jaye: I imagine different personalities in creatives also make it difficult.

I’m kind of the opposite. Every band I work with, every creative thing, I want that to be collaborative. When I meet with a band or an artist … I have zero ego involved in this. This is not me. This is how you want everybody to see you. …

After some discussion, the two creative forces come to a conclusion: The artistic worlds they both work in are dominated by males. They speculate that patriarchal structures from the 20th century kept many women from achieving fame and success in their careers as musicians.

Jaye: … It is getting much better. I’ve noticed, especially in the drum world, we have some absolute murderers behind the kit and they are strong, beautiful, dainty, lovely mothers. Nurturing, precious, but they will eat your whole face off when they’re behind the kit and I love seeing that so much.

Nelson: That needs to be encouraged more. Young women need that encouragement because I think there’s so much messaging that’s opposite of that.

Jaye: … I’ve been seeing a lot of older women picking up drums. It’s incredibly therapeutic and, when you’re fighting against things like memory-related diseases or degeneration, drums cater to both sides of the brain. … If you can tell a little girl or nonbinary child whoever you are, wherever you end up in this world, you have a place at the table, there is no door that is locked to you, that’s incredibly powerful for a child. And I wish as a little kid somebody had told me that sooner. … It took [me] to 30 to say, “I don’t have to fit into this form. I don’t have to be what my pastor, parents, grandmother — I don’t have to be what those people expected of me. I’m allowed to be whatever weird, little freak I want to be and that served me really well.

I work with an organization called G.I.R.L.S Rock and it’s gender inclusive. It’s an incredible program. I did photographs for bands this summer and there was a child. She looked to be about four; I’m sure that that wasn’t her age, I think they have a low limit of like six or seven. She had this giant bass guitar. It was twice her size, but she was holding it.

To be able to give that, [Larisa Bryski, the executive director of G.I.R.L.S. Rock] is doing an incredible thing for the community. I think we’re gonna see a huge swath of young women. Everybody will benefit from that. Just a boom of creativity and deeper music culture in about five to 10 years. Huge.

Nelson: I agree.

Jaye: Have you nearly given up on your career?

Nelson: Not really. I have a lot of feelings about that. I was in Cake for a very long time. People I don’t know come up to me at the [Sacramento] Co-Op and say, “How’s Cake doing?” I ran into somebody that maybe was a Cake fan when Cake played at Old Ironsides. I said “I quit.” And the person said, “Oh, you quit music.” No, I quit a band. People see your professional life, as you and I don’t blame them. I understand. That, to me, never really mattered. …

Going out on tour, making records and doing all the stuff that a professional band can do; to me, that’s like after the fact. The music part is what you do in your living room when nobody’s there — the creative part.

Jaye: Most people need years of the living room part. I feel like the living room part is the foundation and a springboard. It’s the fabric that you have to build the stage part on. If you don’t have yards and yards and yards of that fabric, then the stage will never exist.

Nelson: I don’t care about Side B. You can’t bank on it.

Jaye: Well, and at any moment a contract could fall apart. Somebody could have a vocal cord injury.

Nelson: The music industry can collapse.

Jaye: A pandemic. And there’s no touring and there’s no record sales.

Nelson: There’s not even local gigs.

Jaye: And you’ll still have the living room, even if you don’t have the stage.

Nelson: The pandemic: Nothing changed musically for me. I did the same thing that I always do. I played music every day. I don’t know what giving up means. Does that mean I’m not a professional anymore or not as professional as I used to be? I walked away from that, because it’s not that important. It was kind of more of a burden than a blessing. Nobody understands that. I don’t blame them. I just needed to stay home. I needed to quit leaving my house.

Jaye: A lot of people don’t understand how hard it is to be out and a part of an entity that is working and recognizable. That is a very heavy burden. I’ve worked with a lot of young musicians that just want to be out on the road.

Nelson: Well, they got the spirit of adventure and that’s good. I had that too, but after 20 years of being away from home, I don’t go anywhere now, I just stay home. I should probably get out of the house at least sometimes. My desire to be at home is so strong. My desire to be out of the house is — there’s hardly any.

Jaye: You have to chase your peace.

Nelson: There’s a lot of fun to be had out there too, but nothing’s free. It costs you in other ways. I would have had to quit anyways because my wife got sick about a year later. She needed 24/7 care and surveillance. But what about you?

Jaye: I’ve been doing this for about 20 years. … I get involved. I get attached to people. I am one person and I am a single mom with ADHD and I want to do everything. I want to help everybody and I want to make dreams come true. These thoughts happen cyclically. Usually it happens when I’m burnt out and I push myself past the point of exhaustion and my mental health is unwell. …

Nelson: [How] did you get into photography?

Jaye: In high school, I was the yearbook editor. I was very proud of myself; I did it for two years because nobody else wanted to do it. And I was very self-assured in that space. I did a lot of photography there. After high school, I kept taking pictures — mostly took pictures so I could get into shows for free. I was very much a church kid and there’s this church out in Roseville that did a bunch of like the hardcore screamo shows. That was my jam.

Jaye: There’s not anything else that I enjoy more [than music] and I’ve contemplated it. It’s a means to connection to people and it gives me space to have moments of beautiful vulnerability and joy and share other people’s loveliness with them without having to be creepy. It is different when you can look at somebody and be like, “Your eyeballs look like the Earth. You have the sky and water and the forest inside of your eye holes. And that’s lovely. I noticed this because I’m a photographer. That’s just because I take pictures. I see these things.”

Nelson: I just do it because I want to. I don’t know why I want to, but I do. I always have. I want to make music. And my mom, was like, “OK, you’re gonna make music.” I remember being really young in the car. There was a Motown song on the radio, and I could hear the bass. I recognized that the bass playing was unusual. So I already knew what normal bass playing was from Hee Haw.

Jaye: It was written into your bones before you even knew.

Nelson: I think I was a born bass player.

This conversation has been edited for length, clarity and flow.

This story is part of the Solving Sacramento journalism collaborative. Solving Sacramento is supported by funding from the James Irvine Foundation and Solutions Journalism Network. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, Capital Public Radio, Outword, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review, Sacramento Observer and Univision 19.

Be the first to comment on "Creativity in the Capital: Elle Jaye and Gabe Nelson discuss the difference between being a hugger and a homebody"