Authors craft a chronicle of their 90-mile trek across Sierra Nevada trails

By Frank X. Mullen

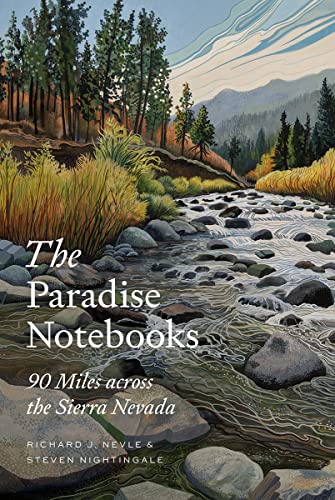

In “The Paradise Notebooks,” authors Richard J. Nevle and Steven Nightingale take readers across the legendary Sierra Nevada range on a journey illuminated by scientific insight and incandescent poetry.

From granite to aspen, to fire, to a rare, endemic species of butterfly, the essays and poems in the book explore the natural history and mystical content of each wild element. As they weave in vignettes from a 90-mile backpacking trip across the range with their families, Nevle and Nightingale powerfully re-conceive the Sierra Nevada as both earthly matter and transcendental offering. They invite us to a vision in which nature holds just as much spiritual importance as it does physical reality.

Here is an excerpt of one pair of essays in the book. In each of the twenty-one pairs, Nevle writes a lyrical scientific essay on one element of the Sierra, and Nightingale follows with a treatment of that same element as it relates to the history of poetry and spiritual texts.

From “The Paradise Notebooks”

“As for the earth, out of it comes bread; but underneath it is turned up by fire. Its stones are the place of sapphires, and it has dust of gold.” —The Book of Job

8/4/17, Day 2. Overcast, damp morning. Views of the glacier-chiseled face of the Great Western Divide between fat red firs sleeved in wolf lichen. Crossed a wooden bridge over the gorge shot through by Lone Pine Creek, then switchbacked up a granite shoulder before contouring back toward Hamilton Lakes Basin. Set up our tents among lodgepole pine groves, near a slab of granite overlooking the water. Watched a rainbow arcing across the peaks of the Divide, waterfalls braiding down dark cliffs. Cold baths for all.

Gazing out across the roof of the Sierra Nevada, one might spy thin black and rust-orange fins of frost-heaved metamorphic rock riding atop bright granite. These fins, known as roof pendants, were travelers once, geologic migrants from the sea. They are scraps of balmy archipelagos and a once vibrant seabed that lay beneath them. They journeyed across the great Panthalassic Ocean, ancestor of the Pacific, ferried aboard a tectonic plate that slid eastward until it encountered western North America. For more than a hundred million years this plate, the Farallon Plate, pulled by its immense, dense mass, bent where it met the continent and descended into the mantle’s scorching interior. Some slivers of seafloor and islands managed to escape, scraped off like skin against the continent’s edge.

With each new addition of some island or welt of oceanic rock to the continental boundary, North America expanded westward in a kind of geologic manifest des- tiny. Bodies of granitic magma swarmed the scraped-off seafaring migrants and transfigured them once again with ferocious heat and pressure. In the last few millions of years, the amalgam of deformed exotic rocks has risen miles into the sky, even as the range has been given line and shape and texture by glaciers and rivers.

Today the maritime origin of the Sierra roof pendants—the remains of plankton, or coral reefs, or submarine lava flows, or of seabed sediments made from fragments of much older mountains—is hardly recognizable. Once horizontal layers of seafloor sediment are now accordioned. The delicate edifices of coral reefs have recrystallized into mosaics of scintillant calcite, revealed in Sierra caverns. Elsewhere, the ancient seabed, where it lies adjacent to the granite, has been swirled like taffy, transformed into assemblages of blood-red garnet, ebony hornblende, glittering varieties of mica, and many other minerals. Some of the pendants’ iron- rich minerals rust into oxides, and where abundant they stain the rock to rich shades of umber and chocolate. Such mineral stains occasionally reveal deposits of dispersed gold, silver, tungsten, copper, and other valuable metals that formed when superheated, mineral-charged waters escaped from crystallizing granite and reacted with the seafloor remnants.

But there is an even rarer treasure among the high-country roof pendants. The distinctive chemical compositions of these geologic travelers give rise to thin scrapes of distinctive soils. Such soils, in the austere climatic conditions of high elevation, nurture gardens with delicate wildflowers you will not find blossoming elsewhere in the Sierra—such as the curiously erotic lavender blooms of Parry’s oxytrope, sleeved in their wooly sepals, and the veined, translucent petals of the small-flowered grass of Parnassus. Into these Sierra flower gardens wander bees and butterflies and hummingbirds. Alpine chipmunks burrow underneath as the shape of a falcon hurtles overhead. Life is a journeywork; life turns to life.

So many, in so many ways, have found in poetry a way forward for the mind and spirit. When we look at how this might be, we return inevitably to inquire about the nature of beauty.

In most cultures, in every century, beauty is bound up with unity. Beauty illuminates the affinity, the inner relation, the resemblance, the kinship, the concord and identity of things. We are all trained to tell things apart. In the experience of beauty, we learn to tell things alike; to move from the darkness of oneself to a sympathy, an open rapport; a longed-for, conscious union with the world. Beauty is a lucid and graceful assembly of forms that calls the mind close to life, our bodies close to the earth, and all of us closer to one another.

We strive for such an assembly, no matter the cost to ourselves; no matter how much we must disappear into the work.

Think of the tectonic plates whose movement carried those islands and reefs across the ocean, until at last most of them disappeared beneath the western edge of North America. Yet some portions survived the journey. What once was cooled by trade winds now is undone and re-created. With the rising of the Sierra Nevada and the revealing work of wind and ice, the material rises again, metamorphosed, into the sunlight. This is the world of resemblance, as in the view of the Zuni: “The sun, moon, and the stars, the sky, earth, and sea, in all their phenomena and elements; and all inanimate objects, as well as plants, animals, and men . . . belong to one great system of all-conscious and interrelated life, in which the degrees of relationship seem to be determined largely, if not wholly, by the degrees of resemblance.”

Mountains are oceans. Over the pass, you may find an island illuminated. On the top of a marble butte in winter, you may be in the tropics. The pastel beauties of coral may be found in hard stone in a dark cave. A passage through once molten rock may make the soil that bears the flower that brings the hummingbird.

In any one place may be held all places. One beauty gathers into itself other beauties. Each world bears all the worlds we might find within it. If you under- stand one outcropping of stone, or one wildflower, or one hummingbird — if we see our way along the tracery of cause and effect, the mystery of change and re-creation — then we are led to everything we see, and everything we are. The earth is inclusive. It includes us, teaching us how we must be re-created by the heat and movement over years of our love and understanding. We ourselves change as we step aside from our practical affairs and give ourselves over, wholly and irrevocably, to the beauties of earth. By such loving, we take on another life, as surely as ancient seafloor and islands turn into the glittering mineral pendants of the Sierra Nevada.

About the authors: Richard J. Nevleis deputy director of the Earth Systems Program at Stanford University and the author of numerous scientific articles. Steven Nightingale teaches poetry in schools and universities in Nevada and California. He is the author of 10 books, including the short fiction collection “The Hot Climate of Promises and Grace.”

“The Paradise Notebooks: 90 Miles across the Sierra Nevada,” by Richard J. Nevle and Steven Nightingale, is a Comstock book published by Cornell University Press. Copyright (c) 2022 by Richard J. Nevle and Steven Nightingale. Excerpts reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Be the first to comment on "Prose, poetry and the beauty of the Sierra merge in ‘The Paradise Notebooks’"