Memoir from Sacramento-area restaurant veteran adds a new flavor to the California Cuisine legend

By Scott Thomas Anderson

Drinkers stepping into the Double A Tap on the Southside of Chicago would barely notice that a 7-year-old boy was pouring their whiskey across the wooden bar.

In that year of 1951, the Double A was part of a battery of houses on Morgan Street that had their living rooms converted to drop-in taverns. The child passing out beer and bourbon was the son of Alphonse and Ann, the two ‘As’ behind the name of the makeshift speakeasy. The 7-year-old’s father was still a dockworker on the graveyard shift, so whenever the old man grabbed his afternoon nap, the boy would dutifully take over his family’s bartending duties. Within the gritty gears of Chicago’s political machine, a simple bribe for the cops was all it took to hold all avenues to the American Dream open. The boy would always remember doing his homework between pouring shots, with some of the den’s bleary-eyed patrons tutoring him over their bottles.

Some might have guessed this industrious kid was preordained to be a server, but no one could have foreseen he’d become an avid newspaper hound and Scrabble-slaying conversationalist who holds the answer to a California cryptogram: And that’s who’s most responsible for changing West Coast dining as we know it? Whose idea was it to embrace the Old World’s fresh farm potential in a way that beautified plates from Napa to Ireland? Which innovator first saw the Golden State’s endless bounty as a catalyst for culinary change?

Until now, the narratives attempting to answer that question have been split between two big personalities working in the same Berkeley restaurant from 1972 to 1978. One camp says that “California Cuisine” was pioneered by the godmother of organic dynamism, Alice Waters. The other says it was unleashed by the fine-eyed contemplative chef-savant, Jeremiah Tower. Both food masters have released their blockbuster memoirs, each making an essential case for their own legacy – and kitchen workers around the world are still wondering about the truth of it.

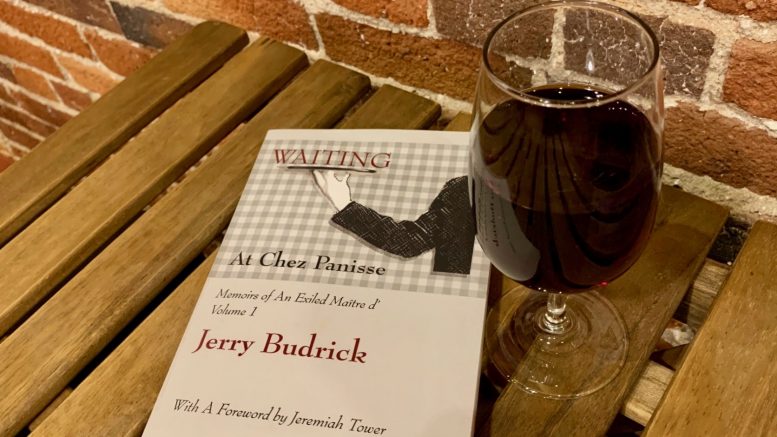

But what is less disputed is that America’s most-coveted cooking style is rooted in Chez Panisse, that rebel restaurant stuffed inside a quirky house on Berkeley’s Shattuck Avenue. And now another voice from this aromatic vault of memories is rising up with a testament: Jerry Budrick, the former 7-year-old bartender from ‘Mud City,’ grew up to be the first head waiter at Chez Panisse. He was also one of its original part-owners. Budrick lives on the outskirts of Sacramento County in the hamlet of Amador City, a rustic, hill-bound paradise that’s given him the daily peace to finally finish his anticipated, Waiting At Chez Panisse: Memoirs of an Exiled Maître d’ Volume 1.

“Nobody at Chez Panisse had been in the restaurant business before it opened,” Budrick stressed. “We just threw ourselves into it and learned as we went; but we knew we didn’t want it to be anything like places that already existed. We knew we wanted something better and different.”

‘Joyous chaos’

Before wandering through the doors of the restaurant that would change his life in 1971, Budrick’s only experience as a waiter involved a brief stint at a lakeside café in Austria. He makes it clear that his lack of experience was key to his lasting contributions to Chez Panisse’s vibe. Just as Alice Waters and her initial partner Paul Aratow were looking to offer a French-influenced dining experience that felt liberated from stuffiness and pretention, Budrick and the restaurant’s other maiden server, Sharon Jones, were more than comfortable with tossing out all formality on the floor.

“We served great food and had a fine wine list, but we didn’t have any of that kind of rigidity that had taken over in all the French places at the time,” Budrick recalled. “I just know we didn’t want to have any of that. We were never formal. If you were the right kind of person, and appreciated what we were trying to do, you could become our friend. We’d be pals rather than master and servant.”

In Waiting At Chez Panisse, Budrick recounts in clarion detail the restaurant’s opening night – and the moment he’d be the face of its wait staff. Waters was casting the atmospheric spell as hostess, in Budrick’s telling, while the premier chef was Victoria Jenanyan Wise, a gifted home cook who would go on to author 14 nationally published recipe books (and later become Budrick’s sister-in-law).

“One thing for certain was we were doing authentic French cooking and that meant, above all, archaeological sauces built up by layers of time and tending to achieve their richness; no cans or pasts or beef stock from the restaurant supply house,” Wise would later detail. “The whole dish smacked splendiferously of good intent, creative effort, and time spent. It was, however, perhaps more properly described as a Mediterranean or California composition, a preview of the tack we all took in the years to come.”

Budrick thinks the real breakthrough that evening was establishing the custom of a changing prix fixe menu – or a menu of the same three courses for everyone walking in. According to him and Wise, the very first dinner served at Chez Panisse was Pâté en Croûte, brazed duck with olives and plum tart. The entire meal rang in at $3.95. Budrick reminisces in the book about a “joyful anarchy” to these early days, a clutter of action that included Chez Panisse’s first dessert chef, Lindsey Shere, as well as the late Royal Thomas Guernsey III, who Budrick calls the best waiter he ever knew.

A year-and-a-half after opening, the team was trying to stop hemorrhaging money and Waters began trying her hand in the kitchen. That’s when a pivotal figure walked into Chez Panisse – Jeremiah Tower. He was answering an ad for head chef, and while Tower had no professional experience, the roving and bizarre circumstances of his upbringing had put him in orbit of some of Europe’s great culinary traditionalists. Most agree that Tower brought highly calibrated tastes and an eye for plate aesthetics, but also shared with Waters, Budrick and crew some renegade sensibilities of his own.

Budrick looks at the era that followed as the true heyday of Chez Panisse.

And the restaurant’s head maître d’ made an impression on Tower, too. In Tower’s groundbreaking 2003 memoir California Dish – later re-published by Anthony Bourdain as Start the Fire – he recounts that Budrick was usually the one backing his best ideas. Start the Fire also contains Tower’s entertaining anecdote of the night when Richard Nixon’s Chief of Staff, H.R. Haldeman, brought his family into Chez Panisse just after Watergate broke. In Tower’s memory, everyone working at the restaurant refused to serve the political hatchet man, while he, as head chef, argued this would violate the basic tenants of service. Tower says that the only one there to back him up … was Jerry Budrick.

Neary 50 years later, Budrick still smiles when asked about the dust-up. He also adds a few details Tower left out.

“Watergate had just been discovered, and Jeremiah’s assistant, Willy, was peeking out of the kitchen and jumped up and said, ‘Oh my God, there’s evil in the dining room!’” Budrick remembered. “The other waiter, James, told me, ‘I can’t deal with this.’ I said, ‘Well, we can’t just not wait on someone because he’s an evil guy. He’s a customer and we’ll deal with it.’”

Budrick began taking care of Halderman’s party. Then, he was perplexed as Tower sent a bottle of Chez Panisse’s very best champaign to their table – on the house.

“I didn’t know it at the time, but Jeremiah did, that Halderman didn’t drink because he was a Seventh Day Adventist,” Budrick said with a laugh. “I found out later that Jeremiah did it just to fuck with him.”

So, who did start the fire?

On the heels of her influential cook books, Alice Waters’ 2017 memoir Coming to My Senses was a particular sensation in Northern California. The following spring, Budrick brought his family to Sacramento’s Crest Theater to watch a large crowd meet Jeremiah Tower. Anthony Bourdain had just produced a documentary about Tower’s life called “The Last Magnificent,” and the tide of public opinion – or at least part of it – was now ebbing toward his side of the farm-to-fork legend. As Tower left the stage to thunderous applause, he saw Budrick and reached out to hug him.

The question of how California Cuisine turned into a dominating phenomenon is something Budrick addresses in Chapter 8 of Waiting At Chez Panisse.

“As fate and luck would have it, I just happened to be there for the entire process of insemination, labor and delivery,” he writes.

Budrick acknowledges the cooking style “has two parents” – Waters and Tower – and his memoir seems like a fairly balanced, open-minded and analytical exploration of how those influences melted together. Budrick’s version of the story is vividly fun and upbeat, while still chalked with concrete culinary details. His chapter on California Cuisine also carries a rare photograph of Waters and Tower working side-by-side in the kitchen, a kind of ying-yang symbol of two talents fusing their energies into an evolving creative endeavor.

This approach may be what ultimately prompted Tower to write a forward to Waiting At Chez Panisse.

“Jerry Budrick, the author of this book, balanced Alice in the dining room beautifully,” the famous chef notes, “and brought professional service to a dining room, sometimes strained by the pressure of a different menu every night and a kitchen that reacted to that somewhat differently than other Bay Area restaurants. But the story is told here – or at least one of the best versions of it.”

Budrick and his wife Deborah went on to own a popular Mediterranean restaurant called Caffe Via D’Oro for years in Sutter Creek. Now retired, his daughter Ginger is making her own splash with Small Town Wine Bar in Amador City. But his memories of Berkeley’s culinary epoch kept nagging him. Budrick realized he needed to set down the story. In addition to highlighting lesser-known figures in Chez Panisse’s story, including Sharon Jones, Lindsey Shere, Thomas Guersney and Victoria Jenanyan Wise, Budrick also sought to explore a question that’s bothered him for decades: How did the restaurant lose its working-class customer base?

Not long after it opened, Budrick became one of its five co-owners. His memoir probes exactly how and why the fateful decision was made in 1975 to transform from this “original partnership of dreamers” to a standard corporation. Now, in our current moment of gaping income gaps and numbing inflation from the 1970s returning with a vengeance, Budrick’s focus in Waiting At Chez Panisse takes on an urgent relevance. It becomes the story of former owners and shareholders such as himself losing more and more control of their democratizing dining vision.

“Our clientele, or friends and fans and regulars, started to not be able to afford us,” Budrick mentioned in a solemn tone. “It was never supposed to be expensive. So, yes, we got famous; but that meant the clientele became almost exclusively rich people from all around the region and all around the country. To me, it was very bothersome, because the atmosphere got more and more church-like – and it was just weird.”

He added, “I hated it – and I was the head waiter. You know, it’s almost sad sometimes to think back on these things.”

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the host of the ‘Drinkers with Writing Problems’ podcast.

Be the first to comment on "Waiting to tell the tale: After 50 years, Chez Panisse’s first waiter decides to dish"