Sometimes our present woes are best understood through the pain others felt in the past

For 45 years May has been the month of the frog at California’s state capitol.

Prior to the pandemic, lawmakers, legislative staff and infamous scribblers would always gather on the East Lawn to watch burly Calaveras bullfrogs make their incredible jumps.

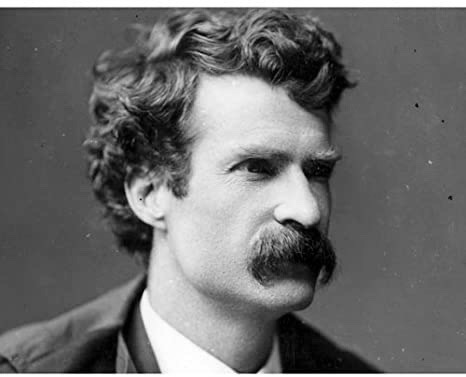

It was an event celebrating the region’s place in American literature. It was here, in Northern California, that a young Mark Twain first gained major notoriety, partly through a newsy shipwreck feature he penned for The Sacramento Union, and partly through a “villainous backwoods sketch” he conjured about an unscrupulous frog-jumping contest in Angels Camp. It’s no exaggeration to say that the latter piece was Twain’s first step in shattering the stylistic paradigm that had defined U.S. letters for over a century.

It was a true turning point.

Given that, anyone of a certain age who grew up in the Sierra foothills, or “Gold Country,” knows the story of how a hapless drifter named Samuel Clemens used our area’s whiskey-splashed culture to become the master of rough American brilliance called Mark Twain. The annual get-together at the capitol – abandoned the last two years due to the health crisis – has been a way of keeping this watermark of the West vibrant in our memories.

While Sacramento won’t have a frog jump to contemplate this month, it may be a perfect time to re-contemplate Twain himself; and not in a political-revisionist kind of way, but as a cautionary tale of what can come of the grieving and wounded human spirit. That is to say, Americans are emerging from an exceedingly dark year, and it’s worth remember that Twain was, in the final tally, an exceedingly dark writer.

Of course, this is not his public image. That’s still firmly anchored to his writings from 1865 to 1885, a period of stormy energy that touched the lightning-life to Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn and a rogues’ gallery of other unforgettable characters. But for Twain, the thunderstruck decade that followed changed everything: He’d lose his fortune to bad investments, his youngest daughter to spinal meningitis and his beloved wife to the march of time. Perhaps it’s understandable that Twain attempted to parry these slings and arrows with creativity. Hence what he wrote in that period, including “The War Prayer,” “The Mysterious Stranger” and “Letters from the Earth,” are among the most socially morbid and nakedly nihilistic pieces ever set down by an American wordsmith. These stories and essays have a heated sincerity – and they’re inventive in the most unsettling kind of way.

If you haven’t heard of them, there is a reason. There’s no mischievous pranksters or mighty Mississippi River here. Just screeds aimed at the sky. Just windows onto smoldering pain and internalized rage incarnate. One meditation from this timeframe Twain titled, “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” and that’s a good description of the only kind of reader he was really writing for anymore.

While these late-stage offerings from Twain might connect with people who are wrestling with cynicism, misery and their own shadow, they also demonstrate what unchecked regret does to personal potential. In my view, Twain was a genius, but the trajectory of his later life raises the question of whether genius can shine through what Jerry Stahl called “a permeant midnight.”

My purpose here is not to over idealize the more nostalgia-laden pieces from Twain’s initial career, but instead to suggest that, at his very best, this writer could control and channel his misanthropy in the subtlest of ways – and that made for timeless reading experiences. A prime example is “The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut,” which is as close as he ever came to penning a ghost story or memory of the macabre. The yarn’s weirdly addictive, and it highlights Twain’s gift for mixing cocktails of sinister humor, existential crisis and boundless doses of irony.

It’s not a coincidence that story belongs to the vital spell that predates Twain’s melancholy orbit; a period when he ranked elevating his art of deadly comedy above railing at the unfairness of the world. It was written as an act of thought-provoking entertainment, rather than one of spiritual retribution hurled from the foggy banks of tragedy.

Ultimately, Twain is too complex, too wildly elusive to fit into canonical boxes. Tales like “Crime in Connecticut” show how amorphous his storytelling gifts really were. But they also prove – by virtue of what came after them – the ways we sometimes cripple ourselves in states of permanent lamenting.

It’s an especially relevant point right now. As the COVID crisis appears to finally be waning, the temptation for “looking back in anger” will be great. Some of us will wonder whether if the C.D.C. had told the truth about the benefits of masking five weeks earlier than it did, maybe someone we knew or loved might still be alive. Others of us will be tempted to look at the totality of data from large states that didn’t aggressively lockdown and wonder if California’s leadership cost us our jobs, careers and businesses for no real benefit to the greater good. And God can only imagine what will come if it’s ever proven that all of this happened because of laboratory negligence around risky gain-of-function research that was partly funded by the U.S. government.

We’re collectively coming out of a moment of great loss, and slowly moving into a moment of rollercoaster reflections. There is no playbook or frame of reference for how we’ll feel (even the Spanish Flu didn’t come with the divisive and isolating power of social media). You don’t have to be a writer, or any kind of creative person, to be in jeopardy of inner paralysis.

We all are.

The question is whether we wall ourselves up in crypts of bitterness, or get whatever help may be needed, and do our best to carry on.

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the host of the ‘Drinkers with Writing Problems’ podcast.

Be the first to comment on "Editorial: Lost moment at the state capitol offers a window onto ‘the person sitting in darkness’"