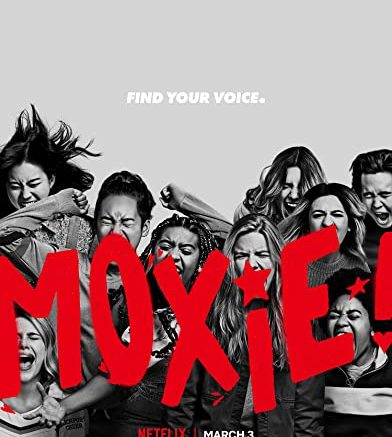

I need to explain from the outset that the game was rigged. In Moxie—released this past Wednesday on Netflix—a teenager empowered by her mom’s feminist punk rock past foments a mini revolution in her high school via a series of anonymously produced zines. I came to Moxie already on guard, not convinced about the sincerity of the movie’s riot grrrl nods and admittedly a little suspicious about the extent to which teenage activist engagement can be accurately portrayed in a big budget studio film.

Punk and hardcore informed the bulk of my teenage ethics, but it was still a boys’ club. The combination of anger, earnestness, and goofiness of riot grrrl was the subsect of the punk community where I felt the least out of place. To borrow from Bikini Kill’s vocabulary, riot grrrl was equal parts Be a dork, tell your friends you love them and Resist psychic death.

So in the spirit of objectivity, I roped my friend Caroline and her husband DP into an outdoor, distanced viewing. Caroline and I have both been in Sacramento for a long time, but in the late nineties, I’d drive into DC from the Virginia suburbs to Caroline’s house for our chapter’s riot grrrl meetings. (A quick aside here to explain that our late 90s chapter was not the original one, not the famous one, whose members had largely relocated or moved on by the time I showed up in 1998). I was relying on Caroline to keep me from being too grouchy and protective and eye-roll-y without cause.

Moxie’s Vivian (Hadley Robinson) is a quietly progressive high school student, but of a very middle of the road, keep-your-head-down variety, to the point that she advises new student Lucy (Alycia Pascual-Peña) to ignore noxious predatory jock Mitchell (Patrick Schwarzenegger) rather than speak up for herself. Nah, says Lucy. “Keep your head held high.”

The words resonate with Vivian; she’s heard them before. She goes home, asks her mother Lisa (Amy Poehler, who also directs) “…it’s from a song, right? You used to play it for me when I was little.”

Oof. Yes. “Rebel Girl,” one of Bikini Kill’s best-known songs, is now nearly 30 years old. “Rebel Girl” plays over a montage of Vivian going through her mother’s stuff, grabbing her mom’s old leather jacket, tugging a band-sticker-covered suitcase out from under the bed. It’s a treasure trove of tapes and zines and a particularly jarring photo of Amy Poehler’s head photoshopped onto Kathleen Hanna’s body. The phrase riot grrrl is never specifically uttered, but we’re to intuit that Vivian’s mother was heavily influenced by the scene, if not directly involved. Vivian spends the evening poring through Bikini Kill-created zines, and soon after, she’s motivated-activated.

Vivian creates a zine—the aforementioned Moxie—in a frustrated, impulsive burst of angry creative energy—calling out some of the more egregious acts of sexism in her school. I can attest to this as being a valid and relatable moment; my teenage years (hell, my adult years) are littered with personal zines birthed from that same strain of anger and frustration. Each new anonymous issue appears in the girls’ restroom and the waves of students—mostly young women—willing to participate in acts of protest grows.

It seems that in a world of social media, and for folks outside of certain subcultures, a self-produced magazine is a foreign concept. Or as Lucy puts it: “It’s a zine. In the Bay Area there are tons at shows, but this is the first time I’ve seen one here.”

Our watch party paused here as we discussed whether or not we were the target demographic for this movie. We are on social media, sure, but we can remember a time before it, and were all of a population where zines were commonplace and where readers were accustomed to small-scale publications that often resembled ransom notes. More to the point, zines are still being created, still circulated—yes, even by high school students. Is this explanation of a zine meant to imbue it with some mystique (oh, that faraway magical Bay Area), or is it an expository line because there’s worry that the average person doesn’t know what a zine is?

Much of the promotional material for Moxie features Amy Poehler saying “When I was 16 all I cared about was smashing the patriarchy and burning it all down.” Though Moxie is based on a young adult novel, the movie sells itself as a little more cross-generational, and, as Caroline put it, “very safe.” DP posited that it was in fact meant to be a mother-daughter movie, and that we might have a better appreciation for it if any of us had kids.

Possibly, but Poehler’s Lisa is largely at the periphery. She’s a supportive single mother happy to sling sarcastic barbs at condescending male grocery clerks. She’s got a nice collection of riot grrrl band tees. She dates a nice guy that she admits she doesn’t have much in common with, a point of contention for Vivian as the movie progresses.

The movie plods. At an hour and 51 minutes, it takes a long time to get where it’s going, and we found ourselves so disinterested that we realized we didn’t know two pivotal characters’ names until 64 minutes into the movie. At the same time, Moxie skips lightly through deeper issues of intersectional feminism, acknowledging issues of racism, LGBTQAI+ discrimination, ableism and class privilege with a quick nod each along the way. Moxie also finds room for a love story and a subplot about the changing nature of close friendships as adolescents, and about mother-daughter dynamics. It’s a lot to cover, and results in very few of the characters feeling well-developed, save Vivian herself.

While Vivian’s anonymously produced zine is the plot’s catalyst, this movie takes place in 2021, and there are group texts and hashtags and protests streamed live via Instagram. The zine is perhaps the last truly anonymous form of communication, where one can both feel truly vulnerable and free while absolving oneself of the responsibility to answer for what’s been created.

And that’s relevant, because other people do pay for Vivian’s effort.

That same anonymity shields Vivian from the retaliation of those Moxie calls out: bro-y white dudes and the school administrators who look the other way at their bad behavior. Or, as her boyfriend Seth (Nico Hiraga) puts it, “seems like you’ve been doing reckless shit and letting others take the blame for you.”

It’s true: her best friend Claudia (Lauren Tsai) cops to being Moxie to take the heat off, and gets suspended. “You don’t get what’s going on with me because you’re white,” Claudia tells Vivian. “I don’t have the freedom to take the risks that you do.”

This is an important moment in the film. There were points in the film where I worried Moxie might skirt the line of the white savior trope, where the machinations of a single white person are implied to have saved the day for everyone. That’s a plausible interpretation. But while the Moxie zines bring together an intersectional group willing to fight not just for feminism, but in the name of antiracism, of LGBTQI+ rights and against ableism, without an identified author Moxie can be whoever they envision her to be. These groups have been empowered to take action by a zine, but also to take actions of their own that extend beyond the scope of what Moxie asks of them.

It’s not a spoiler to tell you that Vivian takes the privilege both anonymity and whiteness offer her and eventually reveals herself, followed by what my movie companion Caroline correctly pointed out as an “I am Spartacus” moment, where swells of female students step up to speak their Moxie truths.

And as abruptly as the transition I’m giving you now, the movie cuts to a club-like party sequence wherein the young women in the cast dance with each other clothed in animal print and metallics. There’s nothing wrong with it. I’m just not sure why it’s there.

Moxie isn’t a perfect movie. It’s billed as a comedy, but my friends and I seemed to miss the jokes. There’s a thread about a college application essay that never fully resolves, and I would have loved a deeper exploration into Vivian’s mom’s journey from snotty feminist punk to grownup—of course I would—but ultimately, Moxie is empowering, at least to the young women who see pieces of themselves in Vivian.

Be the first to comment on "Moxie: Girls (closer) to the front"