Sacramento to levee campers: You have no home, but you can’t stay here.

Days after a Sacramento County health order discouraged homeless sweeps to prevent the spread of COVID-19, approximately 250 homeless people were rousted and given referrals to closed shelters in late May.

That is the central contention of a civil lawsuit filed by the Sacramento Homeless Union against the city and county. The lawsuit claims law enforcement sweeps along Roseville Road and outside City Hall violated a county health order by displacing homeless people during a pandemic without giving them a place to quarantine—putting the public at greater risk of the highly contagious virus jumping from unsheltered communities into the general populace.

Public health officials say that hasn’t happened and point to other reasons for a corresponding rise in novel coronavirus cases.

It likely won’t be known until next year how the virus has affected homeless populations, but two men in their 60s did die outside the Union Gospel Mission following the alleged sweeps in July and August, coroner records show. One of the men last stayed at the mission in November 2019, said Pastor Tim Lane, executive director of the men’s homeless shelter.

In an email, Lane said he wasn’t aware of the deaths until contacted by SN&R and believed they didn’t occur on the campus itself. “Some of the men on our program knew that the men had passed but not of what!” Lane wrote.

During a court hearing last week to determine whether the city of Sacramento violated a judge’s July order to stop conducting homeless sweeps, the city’s attorney said it has no legal obligation to shelter the homeless people it displaces during the pandemic.

The statement was notable because it contradicts the public message coming from Mayor Darrell Steinberg, who has repeatedly invoked a moral obligation to treat homelessness as a humanitarian crisis, as he did in August, when he and other city leaders unveiled a plan to leverage $62 million in state and federal funding to address homelessness and affordable housing shortages.

“This is about humanity,” Steinberg said during the Aug. 17 press conference inside a planned shelter for women. “This is about human beings. This is about our brothers and sisters. But for the grace of God, there go I.”

On Oct. 6, in the relative privacy of a virtual court hearing that was conducted through video conferencing so the parties wouldn’t risk infection, the city’s message was much different.

When the levees are at stake

While Judge Laurie M. Earl ordered the city and county to stop displacing homeless people in July, she ruled Oct. 6 that the city was not in contempt of her order.

Earl stopped short of finding the city’s admitted conduct of evicting homeless campers from the levees appropriate, and provided petitioners with the opportunity to return next month to argue that the city should provide shelter to the displaced.

At issue is whether the county health order carves out an exception for what the city is doing.

The May 22 order directs municipalities to “strictly” follow federal guidelines allowing unsheltered people “to remain where they are” unless they’re provided with “real-time access” to alternative shelter and “a clear plan to safely transport those households.”

Anthony Prince, a Berkeley attorney representing the Sacramento Homeless Union and its fellow petitioners, accused the city of violating that directive by rousting people while providing them referrals to seven shelters that closed in March.

“As it turns out the list is totally fictitious. Every single shelter listed has been closed for months,” Prince said at the hearing. “The city is representing itself all over the map, making conflicting statements, giving out fictitious lists that it knew or should’ve known were false, and trying to have it every way that they want to have it without any kind of accountability.”

The city’s senior deputy attorney, Andrea Velasquez, claimed her client is permitted under the county health order to clear encampments that adversely affect critical infrastructure, which the levees are considered, and doesn’t have to provide housing in such cases.

She acknowledged that the city doesn’t actually know if the levees have been negatively impacted by homeless camps, but said workers won’t be able to ascertain that until the camps are gone.

“It’s October. [The] rainy season is coming,” Velasquez told the judge. “We need to make sure our levee systems can withstand the high-water events that happen every year in Sacramento. We need to make sure that these communities that surround Morrison Creek don’t flood.”

What the order says

The county health order says not to relocate encampments or confiscate homeless people’s belongings during the pandemic, as either action “causes people to disperse throughout the community and break connections with service providers, increasing the potential for infectious disease spread.”

The alleged sweeps, days after the order was issued in late May, coincide with when the novel coronavirus began quickening its spread through Sacramento County.

But this is also the time frame when the county allowed some businesses to reopen. Public health officials, meanwhile, have blamed the rise in infections on people flouting physical distancing guidelines to participate in family gatherings, church services and Memorial Day revelries.

The county’s COVID-19 dashboard shows infections saw a mid-June bump and peaked by mid-July. It generally takes two weeks for symptoms to present. Nearly 24,000 people have been infected by the virus and nearly 460 have died from it in Sacramento County, more than half in the city of Sacramento. It’s unclear how many of them experienced homelessness.

The order does allow for the removal of encampments that “pose an imminent and significant public safety hazard, such as a large excavated area of a levee.” But whether it exempts municipalities from providing immediate shelter in such cases is the issue Prince and Velasquez debated, and that Judge Earl will decide at a later date.

“The city’s position is that if you are clearing an encampment under the exception of ‘adverse impact to critical infrastructure,’ you don’t then go back and provide housing,” Velasquez said.

Then why did the city refer people to closed shelters, retorted Prince, who accused the city of “conducting a PR campaign.”

“We don’t contest the need for keeping the levees safe,” Prince continued. “And we don’t contest the amount of time it may take to make the repairs. But the county health order from our standpoint is clear: You must limit community spread. If you break up the encampment, you have to provide the housing.”

“Mr. Prince, I’m glad this is so clear to you because it’s not that clear to me,” responded Earl, who rejected petitioners’ request to fine the city $5,000 a day until it could shelter the displaced.

The judge reminded both attorneys that Olivia Kasirye, the county’s public health officer, is a named respondent in the suit, meaning she could be called to clarify the order’s intent.

Outside the courtroom

The court battle may be decided in a legal vacuum, but it isn’t occurring in one.

At the August press conference, Steinberg said 1,100 homeless people were granted temporary shelter in motel rooms through Project Roomkey, a state initiative created in response to the pandemic and its economic effects.

“COVID has made the homeless problem even worse,” Steinberg said in August. “We must and we will tackle it on all fronts.”

The city recently opened its temporary women’s shelter in Meadowview, but had to halve capacity to 50 guests to maintain physical distancing standards.

In the meantime, enforcement continues.

Sacramento County Regional Parks rangers have cleared 1,063 camps through August. Last month, the Sacramento Police Department arrested or cited seven people for trespassing violations. Three were cited for other crimes, such as drug possession, carrying a concealed dirk or dagger and vandalism. Four of the arrested individuals were Black; all were men. No one had a home address.

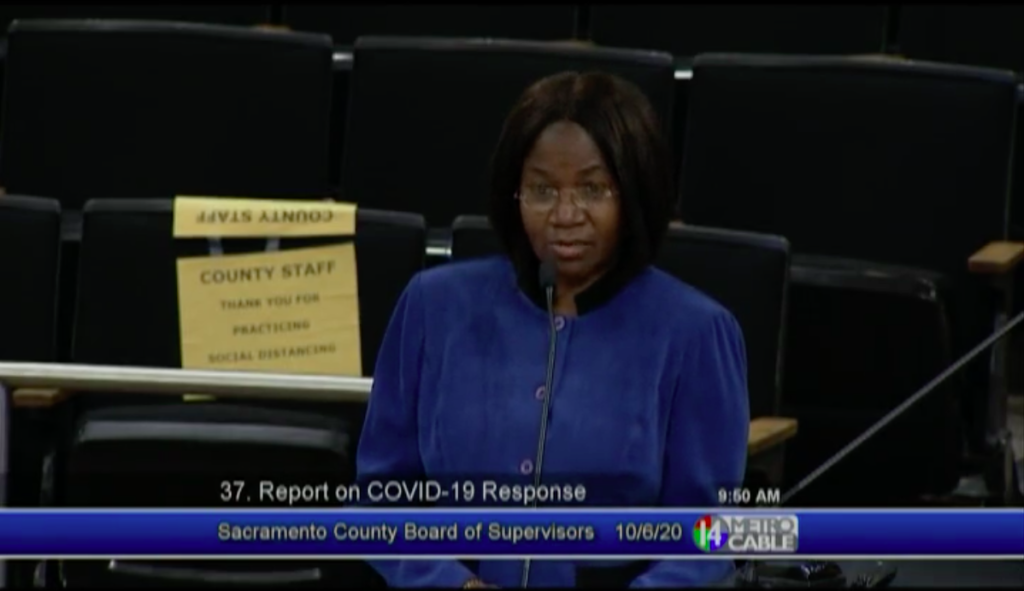

The same day Judge Earl suggested bringing Kasirye into their courtroom discussion, the public health officer told county leaders that Sacramento has so far avoided a COVID outbreak in the homeless population.

“The success is we have not had an outbreak in this population,” Kasirye told the county Board of Supervisors.

Bad political math

Since March, the county has tested 1,703 homeless people, with 92 results coming back positive for COVID, which translates to a 5.4% positivity rate, slightly higher than the 5.3% positivity rate for the entire county.

While that’s a relatively good figure, at least one supervisor thought the rate was a lot lower than it actually was.

During the Oct. 6 meeting, Supervisor Susan Peters mistakenly claimed the tests showed a half-percent infection rate in the homeless population—not 5%—and suggested redirecting money from the program that funds the tests.

“We’re doing so well here, maybe we can spend resources somewhere else to make the rest of the population less likely to have it,” Peters said.

Peter Beilenson, the county’s health services director, deferred the recommendation to a future meeting. No one corrected Peters.

Referrals to closed shelters, a levee loophole and a county supervisor’s bad math—it’s amazing Sacramento has avoided a homeless COVID crisis.

Rousting homeless people who are already down and out is a crime against humanity. This heartless practice certainly doesn’t pass the WWJD test. A Christian would provide shelter. For someone to call themselves a Christian while rousting homeless people, or ordering police to do so, is blasphemy.

Presumably homeless people camping at Cesar Chavez Park or on K Street Mall who were evicted would be legally entitled to a place to quarantine, provided by the city.