How small distilleries solved a big breakdown in rural communities’ supply chain when it mattered most

By Scott Thomas Anderson

Towns across the Sierra foothills may never think of the slogan “buy local” the same way again.

That’s because a group of locally owned distilleries managed to solve a dangerous breakdown in the supply chain as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded. Innovating on the fly, the distillers used their vodka, whiskey and gin operations to make gallons of medically approved hand sanitizer, which they gave to health care workers and first responders who were beginning to run out.

As the coronavirus continued to spread, the distillers then offered their new sanitizer to anxious and at-risk shoppers facing empty store shelves.

Now, as profits for Amazon, Target and Walmart soar—and revenues for many small businesses fall off a cliff—one thing is clear to rural residents living between Jackson and Nevada City: In a moment of uncertainty, it wasn’t national brands such as Purell who kept their communities safe, it was business owners from their own backyards.

Rooted at home

Anchoring a distillery in the California Mother Lode takes a leap of faith. Two years ago, Dan Kennerson and Jon Dorfman took that leap when they opened South Fork Vodka far from the state’s commercial hubs and distribution centers. The partners had worked together before, conducting ethanol research for the U.S. Department of Defense, which led to a breakthrough in their understanding of extracting fusel oil from corn.

In 2018, Kennerson and Dorfman decided to wield their discoveries in chemistry and physics toward creating something for the celebratory side of life. They also decided to launch that project where they both grew up in Nevada County. Locals were excited. What the duo is distilling is a GMO-free vodka made from gluten-free corn and pure mountain water, all run through a signature fusel oil control process. The result is seriously calm, surprisingly clean vodka with a distinct taste of glacial ice.

Getting a distillery off the ground isn’t easy, but South Fork quickly found support from its surrounding business owners. One of the oldest saloons in Nevada County, the Golden Era, offered to highlight the vodka to the thousands of visitors coming through. Friar Tuck’s and the Chief Crazy Horse Saloon, two of Nevada City’s biggest tourist draws, soon did the same. Cirino’s in Grass Valley even made South Fork Vodka the new cornerstone of its nationally famous Bloody Mary.

Kennerson says all this local support helped springboard his label to becoming the top-selling vodka in northern California in 2019.

Sixty miles south in the Gold Country, Cris Steller was having his own success with the Amador & Dry Diggins Distillery. Steller is a spirits enthusiast who worked around the tequila industry before founding the Dry Diggins in 2012. He based the distillery in El Dorado Hills and, a few years later, took over the Amador Distillery across the county line in Jackson.

Steller’s team now produces more than 25 different labels of whiskey, gin, brandy, rum, vodka and liquors. Their emphasis on a steady, well-timed aging process has led to lead some triumphs, including the crisp, delicately spiced melon reflections of its Engine 49 straight bourbon whiskey.

While Dry Diggins bottles are starting to appear on store shelves alongside heavyweights such as Clyde Mays and Basil Hayden, Steller has stayed focused on connecting with customers in El Dorado and Amador counties through tastings and tours at his facility, which is set on the edge of the rolling ranchlands near the counties’ border.

Steller says a lot of the regular faces who come through the doors are law enforcement officers or first responders. That factored into his decision-making when the COVID-19 catastrophe hit. So did Steller’s work with the California Artisanal Distillers Guild. He’s a founding member and has worked with distillers across the state. That includes the team at Gold River Distillery in Rancho Cordova, which would soon help coordinate his efforts as the coronavirus drama unfolded.

The backyard buttress

South Fork Vodka’s team was fully invested in the concept of local synergy, so when it got a call from Sierra Memorial Hospital in Nevada City, it knew things were serious.

Hoarding and panic-buying had led to the hospital running alarmingly low on hand sanitizer. The same thing was happening at the sheriff’s office, the police station and the local firehouses.

Researchers are still trying to determine how transmissible COVID-19 is on surfaces, but maintaining clean hands has been a primary guideline for self-protection from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Thoroughly washing hands often is considered the best practice, though hand sanitizer is the main backup when soap and water aren’t available. That situation constantly comes up for law enforcement officers and firefighters on emergency calls. Many experts also recommend using sanitizer to disinfect frequently touched objects and work spaces.

Sierra Memorial’s staff asked if Kennerson and Dorfman if they’d consider using their vodka stills to help. The two didn’t hesitate to get a formula from the World Health Organization and figure out how to make hand sanitizer. As South Fork’s five-employee team went into action, it learned that law enforcement, firefighters and senior care facilities from Chico to Auburn were also running low.

“We heard from the Apple Ridge senior care facility, and they were very concerned,” Kennerson remembered. “In the beginning, we were trying to prioritize getting the sanitizer we were making to those who were most at-risk.”

Meanwhile in Amador County, Steller was becoming aware of the same meltdown in the supply chain. He watched the news as coronavirus patients disembarked from the Grand Princess cruise ship in Oakland, but the gravity of the situation didn’t fully set in until Steller dropped by his regular janitorial supply store.

“I went in to buy cleaning products and everything was sold out,” Steller said. “I asked them, ‘Well, when will you have more?’ and they said maybe in July. I realized, that’s insane.”

He added, “A lot of production is so centralized now that, even before they shut down the state, you could see where this was going.”

“Early on, even we had trouble getting hand sanitizer. They stepped in and filled the void.”

Bob Hartmann, deputy public health officer for Amador County

Steller and his head distiller Casey Newman studied the formula from health experts and made their first batch of sanitizer five hours later. Dry Diggins quickly started supplying local health workers and first responders, as well as Sutter Amador Hospital, Marshall Hospital, senior care facilities and Veterans Affairs medical centers.

Bob Hartmann, deputy public health officer for Amador County and a member of its COVID-19 emergency team, says he’s impressed by the community service that Dry Diggins has provided.

“We have bottles of it here in the emergency office command center and we use it to sanitize our work spaces, so it’s been a real benefit to us,” Hartmann told SN&R. “Early on, even we had trouble getting hand sanitizer. They stepped in and filled the void. And what they’ve made hits all the quality metrics.”

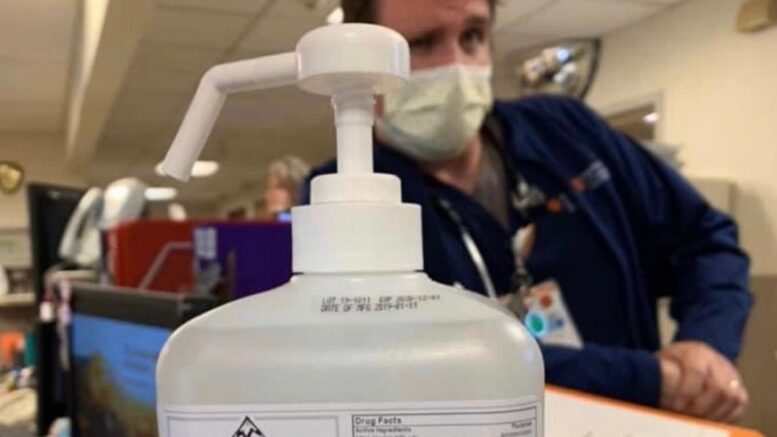

While Dry Diggins and South Fork Vodka each had the equipment and chemistry skills to create desperately needed sanitizer, both were experiencing roadblocks from the very supply chain they were trying to fix. Small bottles and compression pumps for bottles were almost impossible to order. For a while South Fork was hand-filling its sanitizer directly into regular glass vodka bottles.

“There are times a compression pump is worth its weight in gold,” Kennerson noted.

Other distilleries in northern California had to overcome similar obstacles to create hand sanitizer, including J.J. Pfister Distilling Co. in Sacramento, which has worked to get some of its bottles to those in homeless camps, and Savage & Cooke distillery in Vallejo, which quickly hired out-of-work bartenders and servers in early March to help get its sanitizer to the masses.

Eventually, South Fork was confident that it could continue supplying sanitizer to all of the health workers and front line responders in Nevada, Placer and Butte counties. But there was still the problem of sanitizer constantly selling out in those areas, especially at larger grocery chains. Kennerson and Dorfman started selling their new sanitizer through smaller, locally owned businesses—the fastest deals they could strike to get it to the public. Stores including SPD Markets in Grass Valley, Bonanza Market in Nevada City and 1-Stop Market in Auburn are all carrying it now.

Steller also knew his friends at Gold River Distillery were having success producing small, personal use bottles of sanitizer so he decided to refer all the people calling him for that size to Gold River, while his team would focus on bottling larger quantities for businesses and organizations. Dry Diggins has been producing 100 to 300 gallons of sanitizer a day and is currently selling 1 to 275-gallon totes at the distillery.

Steller believes he’ll be making hand sanitizer until at least the end of the year. “Our so-called new normal is going to include using this,” he said. “And from what we’re hearing, the regular market won’t be able to keep up with demand.”

J.J. Pfister Distilling is also selling hand sanitizer directly to the public through its website.

As of two weeks ago, Nevada, Placer, Amador and El Dorado counties had begun reopening most businesses that deal with customers face to face. Making that happen means keeping work places as clean as possible. Thanks to the distilleries that jumped in at the right moment, some degree of stress has been alleviated.

“I’m just glad we were in a business that put us in a position to help in a time of need,” Kennerson said. “And the community gratitude we’ve gotten in return has been phenomenal.”

It has been a similar experience for Steller.

“It feels good to have kept busy through all this,” he said, “while still doing something meaningful.”

Be the first to comment on "The critical hour"