By Scott Thomas Anderson

Les Heinsen keeps his hand on the wheel of a Kubota RTV, his eyes casting ahead at the bronze blanket of fallen leaves that’s scattered under dense pines. The dirt path gets steeper. Heinsen steadies his foot on the gas. The acronym for what he’s driving — Rough Terrain Vehicle — says a lot about the condition of this mountain trail in El Dorado County.

It’s a little bumpy, but Heinsen never tires of its views.

The patch of timberline begins thinning, yet the metallic squeaks of the RTV’s suspension against a weather-struck roughness in the road only grow louder. Turning the bend, the hill opens out of a canopy of tangled branches to reveal green grass and wildflowers and a gray, ancient-looking oak tree. Heinsen moves through this picture until he reaches a brushy summit under the clouds.

He’s at 2,400-feet above sea level. He sees views across the vineyards for his winery, Element 79, and past its trellis rows, the vista becomes all-encompassing — nothing but fresh air and blue sky and the panoramic majesty of the Sierra Foothills.

Heinsen and his wife, Sharon, aren’t hoarding this look-out for themselves. They share it with visitors to Element 79 in a feature they call “Tour to the Top.” Wine club members can reserve the tour for free, but anyone who’s tasting can take the trip by appointment.

“We’ll bring them up on the Kubota and drop them off,” Heinsen says. “They can take some food up, and some wine; and we can also do a hosted tasting for them, too. Or, they can just say, ‘Let us take some snacks and bottles and just leave us alone.’”

Element 79 is part of The El Dorado 8, a group of family-owned, mostly high-elevation wineries that have been sharing farming and fermentation techniques with one another since 2021. The group, which is an unofficial marketing and education collaborative that pays annual dues, is working to bring El Dorado County’s vino reputation to the next level. The excellence found in their tasting rooms is getting noticed by critics, though most visitors are equally inspired by their pristine pastoral settings.

Several years ago, the writer Pico Iyer started popularizing “cyber sabbaticals,” a concept that involves briefly unplugging from the stress and distractions of online life. Some Americans are now spending serious money to get help with closing their laptops, turning their phones off and leaving their Apple watches at home, mainly through forms of isolated agritourism. But big bucks aren’t always needed. The El Dorado 8’s wineries are only 45 miles east of Sacramento and — separately or together — offer a calm, afternoon-long escape from online temptations. They’re portals for connecting with nature through stirring atmospheres alongside a glass or two of expertly crafted varietals. At some stops, that means practicing yoga among the vines at sunrise. At others, it means hiking a trail through trees, orchards and slopes bustling with livestock. At Element 79, it’s about hopping on the Kubota and going on an engine-chugging ride upward.

Heinsen, who’s put a lot of work into perfecting zinfandel, rosé and syrah, thinks the rustic opulence of this mountain getaway speaks to his winery’s broader ethos of relaxation. His “Tour to the Top” is a manifestation of that.

“When we’re spending time up here, there’s no Wi-Fi at all — and it’s pretty cool,” he acknowledges. “The drive here, I call it bucolic. You’ll see cows, you’ll see wildlife. It’s just very soothing.”

Family histories, family visions

Tucked under the hills near Placerville is a gorgeously faded piece of the past. It’s a relic homestead constructed at the end of the Gold Rush, and its walls stand only 10 miles south of where California’s first nugget came out of the river. The landmark was the home of Giovanni Lombardo, a Swiss-Italian immigrant who wanted to plant his own vine-laced piece of the Old World under the sun. Today, Lombardo’s dwelling has cracked stucco clinging to its fieldstone walls and a time-tested slant down its battered balcony. Everything about the structure, from the rust-colored age of its roof, to the crossed iron bars on its cellar windows, hints at the pioneering spirit of those who first tilled the land. For generations Lombardo’s property was a working vineyard. Local lore holds that it even operated through Prohibition by selling wine to the Catholic Diocese.

But El Dorado County’s land usage changed dramatically by the time Prohibition was repealed. Before 1920, the French, Basques, Italians and Eastern Europeans who’d staked a claim here were able to make grapes thrive in the soil. That was before America’s rabid Temperance Movement took its pound of flesh. According to local farmers, El Dorado County went from having several thousand acres of grapes planted in 1900, to only about six acres in 1950. Most growers had switched their focus to pear crops.

It looked like El Dorado’s wine legacy was over.

Then, in 1972, a young couple named Greg and Sue Boeger arrived. Greg was employed by the California Department of Food and Agriculture, and Sue was a social worker. The couple had an idea that sounded improbable, and perhaps to some, overly ambitious: They were looking for a spot where they could use their life’s savings to get a winery started. One person who didn’t think the pair was loopy was El Dorado’s then-Agricultural Commissioner, Edio Delfino. He knew the county had a forgotten story of vino greatness from days gone by. Delfino was ready to help the Boegers revive it.

At that time, Lombardo’s original 70-acre spread outside Placerville — with its Gold Rush-era winery and century-old fig trees — was not even on the market. However, Delfino had inside information that Lombardo’s great-grandson, Elmo Fossati, didn’t have much appetite for driving his tractor through the pear orchards for even one more season. After some colorful negotiations, the Boegers convinced the old-timer to sell. The couple then moved into the property’s weathered homestead and stone wine cellar.

“My parents talked about how when they were looking at this place, they were sitting under the fig trees out there, and they just had this magical feeling,” says Justin Boeger, Greg and Sue’s son. “They knew this was the place.”

The Boegers decided to plant cabernet and merlot, as well as a grape that the early immigrants had once cultivated on the hillsides — zinfandel. Greg was eventually able to get some barbera clippings from an abandoned 19th Century vineyard in Placer County and used those to revive a style of wine that his operation would become famous for.

Justin, now Boeger’s head winemaker, remembers riding a farm tractor by the time he was 10 years old. Justin also recalls the many evenings his dad and Edio Delfino would be chatting for hours about how to make their wine gambit a success.

“When I was a kid, they’d be hanging out in the shop, talking about farming, talking about water issues — local politics,” Justin mentions with a smile.

Before long, there was another man hanging out with Greg Boeger and Edio Delfino: Dick Bush. He and his wife, Leslie, had arrived in El Dorado a year after the Boegers. The couple was interested in starting a vineyard on a 32-acre piece of property studded in madrone trees. Working with Edio Deflino, the Bushes started planting grapes at the 3,000-foot elevation mark. They were on the path to pioneering high-elevation winemaking in the state. They called their little haven Madroña.

“With our elevation up here, and the combination of the soils and the climate, our vines bud a little bit later than everybody else in California, and what that means is that we’re never pushed into harvesting near the intense heat of the summers here,” explains Paul Bush, Dick and Leslie’s son. “It’s shorter days, cooler nights and longer hang-time for the fruit. And what that gives us is a great intensity of character and incredible color in the wine.”

As Boeger Winery and Madroña Vineyards were getting off the ground, Delfino started growing grapes on his own farm at 2,750-feet in Camino. He wanted to help the new winemakers get their feet planted, though — as ag commissioner — much of Delfino’s energy went into dealing with the fallout from the pear blight of the 1950s. Delfino was convincing local farmers to follow his lead in planting apple orchards. In doing so, he became a pioneer of the now hugely popular destination, Apple Hill. Some 40 years later, Delfino’s grandchildren, Christine Delfino Noonan, and Peter and Derek Delfino, all earned various university degrees related to the wine industry and ultimately moved home to start Edio Vineyards on the trailblazer’s storied property. Granddaughter Hannah Melton is also working in the tasting room now.

The Boegers, Bushes and Delfinos were at the forefront of wine in El Dorado in the 1970s; but by 1981, they were getting reinforced by another couple who had moved in, David and Jeanne Jones. David was a geologist from UC Berkeley who started planting grapes just two miles west of the Bushes. In a handful of years, the Joneses, with their son Charlie and daughter-in-law Noreen, had established Lava Cap Winery in Camino.

“My grandfather knew he wanted a moderate climate, so he didn’t want to go to the valley,” notes Lava Cap’s current winemaker, Nolan Jones. “He ended up spending the first 15 years of Lava Cap’s life making it, essentially, a research station for studying the climate of our location.”

Lava Cap Winery, Madroña Vineyards, Edio Vineyards and Boeger Winery are now all members of The El Dorado 8.

Yoga in the vines, trails through the woods, tasting in the bowers

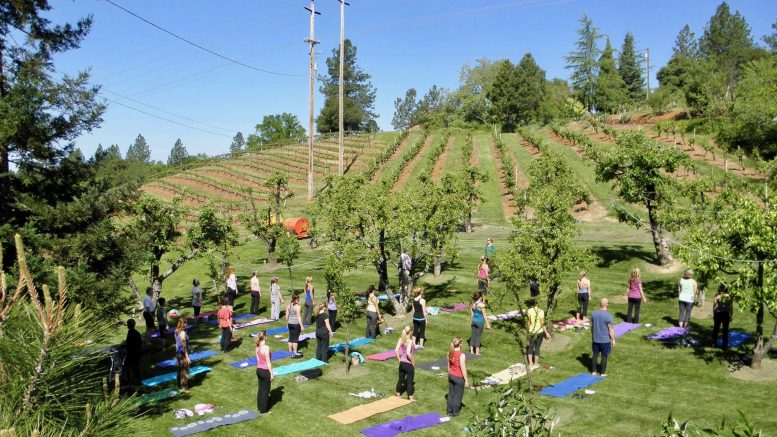

Sunlight crests a washing wave of hilltops, and as it reaches through one of the dips, it touches people gradually stretching their limbs toward daybreak. If the purpose of yoga is to seek mind-and-body unity, few things inspire that journey more than Nature itself. That’s why the Boeger family came up with Woga, their morning-time yoga sessions surrounded by the vines. They host this series on certain dates in April through October.

“We’ve been working with a yoga instructor out of El Dorado Hills for many years,” says Rebecca Stoddard, Boeger’s general manager. “It’s held in our orchard before the winery opens to the public. When you drive in, the birds are chirping, and the sun is shining, and the breeze is flowing — and that’s the setting you have for an hour of yoga. Afterwards, you get to enjoy a glass of wine.”

She adds, “So many people, when they come here, they say it’s just enchanting — like they’re transported to another world.”

One person who loves sharing this luminous atmosphere is Greg Boeger. Now in his 80s, Greg remains the same grape-farming, tractor-riding vineyard manager he’s always been. He and Justin want others to get a sense of the land’s rejuvenating vibes.

“Dawn in the summertime down here is just so delightful,” Justin stresses. “And with Woga, you’re getting to enjoy the grounds the way we do, when they’re not full yet with customers.”

About four miles northeast of Boeger, Sacramentans can also embrace these hills through Edio Vineyard’s nature trail. It’s a walking path that guests can stroll down while carrying a glass of wine, one that goes twisting and turning through the woods, a working vineyard and an Apple Hill farm. The path begins at the property’s stunning overlook and ends at Delfino’s stables that are packed with goats and sheep.

“We often refer to our wines as mountain alpine wines, because, when you’re here, you realize that we’re literally in the pines,” Delfino’s granddaughter, Christine Noonan, points out. “I’m [a] firm believer in exploring, and taking in the fresh air. You can see the whole property. … You end your walk by the sheep that run through our vineyards, as well as our goats. There are ducks and turkeys in the fall.”

Between Edio Vineyards and Boeger Winery is Lava Cap, with its open-air tasting space that gazes out on a shire-like rambling patchwork of hills. It’s an ideal locale to pair soothing scenery with bottles of chardonnay, especially its reserve vintage, which the Jones’ describe as having “a rich finish that compliments bright flavors of lemon and green apple.”

Another meditative sipping spot awaits at Madroña. Its tasting room is fronted by a rustic collection of picnic tables in a tree bower, an oasis shaded below ponderosa pine, incense cedar, crimson madrone and a spattering of wild dogwood. Visitors see Christmas tree farms sprawling in the distance, and they breathe in the fresh scent of the Sierra while savoring Madroña’s offerings. That includes what renowned wine expert Darrell Corti has characterized as an extremely rare and impressive old vine riesling. An oenophile wouldn’t taste anything like it except at 3,000 feet.

“I’m not a holistic person, but I think there is some sort of combination of drinking and tasting the wine out in the vineyards they’re from,” Paul Bush reflects. “There’s certain connections you get by doing an outdoor tasting, especially when the weather up here is spectacular. And even when it might be a hundred degrees in Sacramento, it’s going to be 85 degrees up here with a breeze through the trees. It gets all the other senses going.”

New blood, new vistas

Les and Sharon Heinsen were not the only newer family to build a vino dream in El Dorado when they opened Element 79. Tom Sinton and his son, Rob, founded Starfield Vineyards & Winery in 2011, bolstering the grounds of its tasting area with a long, transporting rose arbor that stretches down to a lake hemmed in trees and dotted in water lilies. This complement to their wine bar makes for easy hikes or strolls after tasting. Starfield Vineyards is another member of The El Dorado 8.

There’s also Miraflores Winery, which was established by Victor Alvarez, a pathologist from Colombia. Alvarez planted his vines along a tumble of hills that’s far removed from any town, then built a Mediterranean-minimalist villa overlooking them, one adorned in pieces of history that include a 15th century fireplace and beams from the Oakland ferry building. Over the years, Miraflores has gained a reputation as having some of the most environmentally friendly farming practices in the entire region. Miraflores joined The El Dorado 8 in 2021.

And practically neighbors to Element 79 is Gwinllan Estate Winery, which is owned by Gordon and Chris, who immigrated from England some years ago. Their son, Jonathan, was only four when they made the move: He lost his charming accent and later became the least-popular member of the family with wine tourists — at least, according to how Jonathan likes to joke in the tasting room. Yet, as a winemaker, he’s made up for his humdrum voice by producing Champagne-style wines that are grabbing attention across Northern California. These elegant pours of bubbly can be enjoyed in front of Gwinllan’s hill-top cave with its sublime, wide-ranging views from the Auburn Ravine to Pyramid Peak in the Sierra.

Approaching Gwinllan, guests pass by grazing cattle and orange poppies painting the swaying grades. It’s the very view that Gordon Pack saw the first time he ventured up this road. Gordon was looking to retire in a vineyard, particularly one that could produce zinfandel and rhône varietals that he loves pouring in the evening time. He spent two years traveling up and down Highway 49 to scout properties from Arnold to Grass Valley. It was only after Gordon strayed off the windy prospectors’ highway near Placerville that he finally discovered a high-elevation escape his heart connected to.

“Highway 49 was almost the exact altitude that I wanted, above the cloud line and below the frost line,” Gordon remembers. “So, we came up here and I stood on this ridge top, and it was just like the piece of land we had in England. It’s in the middle of nowhere — rolling hills. I thought, ‘Well, it’s just so peaceful here.”

That serenity comes from the tasting room’s 360-degree view spanning much of the Tahoe wilderness. There are other touches that make it transporting: Arabian horses grazing near the fence; the Packs’ border collies greeting visitors and frolicking around the vineyards. During harvest, Gordon takes people on walking tours through the vines, letting anyone pick fresh grapes off the budding and thus get a straight taste of Nature itself.

Other touches are more idiosyncratic. After countless guests remarked that Gwinllan’s wine cave resembles a hobbit hole, the Packs threw a party one year where they converted their subterranean scene into Bilbo Baggins’ den, complete with a Tolkienian round door and Gordon growing his beard out and donning Gandalf’s wizard attire.

“Most of the feedback from visitors is just how much they love my parents,” Jonathan mentions, laughing.

Lee Hodo, founder and marketing director for The El Dorado 8, thinks everything about Gwinllan makes it ideal for unplugging from cyber life.

“This is the place I send people who never really appreciated the synchronicity of vines and the mountains,” she observes. “And if you want a mountain view, this is the view.”

The Pack family is working to accentuate the ambiance by adding a French-style bistro to their tasting room. They’re also contemplating holding some wine and star-watching events that would capitalize on the liberating darkness of their night skies.

“We’re so far away from everything,” Jonathan acknowledges. “Our closest neighbor is a quarter of a mile. It’s really that tranquil spot everyone’s looking for. So many people love to come up here, and sit on the patio outside of the cave, and just be in awe of everything as they relax with friends to decompress. This is a spot where you can completely unwind.”

This story is part of the Solving Sacramento journalism collaborative. Solving Sacramento is supported by funding from the James Irvine Foundation and James B. McClatchy Foundation. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, Capital Public Radio, Outword, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review, Sacramento Observer and Univision 19.

I love all the wonderful wineries we have so close to Sacramento! We are so fortunate to live in such a beautiful area

Interior Designer Sacramento https://www.designedcurated.com