Supporters say the legislation would protect farmworkers from employer intimidation.

By David Bacon, Capital & Main

This story is produced by the award-winning journalism nonprofit Capital & Main and co-published here with permission.

Lourdes Cardenas has worked the fields in the San Joaquin Valley for more than 20 years. “I’ve worked in all the crops — grapes, cherries, peaches, nectarines. I’m marching because I want representation and to be respected,” she said. The respect she and other farmworkers seek is not only from their employers, but also from Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Cardenas and members of the United Farm Workers (UFW) are supporting a proposed law to make it much more difficult for growers to use workers’ fear against them in unionization votes. Their proposal would extend to farmworkers the right to vote at home instead of in the fields, among other protections.

Cardenas said that change would mean they would “not be intimidated by the bosses because we want a union. If we have to vote in front of them, they intimidate us, make us fear they’ll fire or suspend us.” According to the California Poor People’s Campaign, “AB 2183 would give more choices to farmworkers so they can vote free from intimidation — in secret, whenever and wherever they feel safe.”

California legislators have agreed. Fifty signed on as sponsors of AB 2183, the Agricultural Labor Relations Voting Choice Act, authored by Assemblymember Mark Stone (D- Santa Cruz). It passed the State Assembly on May 25 by a wide margin, and was sent to the Senate floor on August 11, where its passage is virtually certain.

Newsom, however, has not made a commitment to sign it. A march to gain the governor’s signature began in Delano on August 3. Twenty-six people made a commitment to walk for 24 days up the San Joaquin Valley, all the way to Newsom’s Sacramento office. Each day marchers and supporters cover between 9 and 18 miles. UFW Secretary Treasurer Armando Elenes even counts the steps in a program on his cellphone. On the fifth day it recorded 14,000 paces.

In August, the heat in the San Joaquin Valley is intense. “As we’re walking in temperatures over 100 degrees,” says UFW President Teresa Romero, “I look to my right and I see farmworkers working. That’s what they do every day, day in and day out. They can’t do what we just did. When we get tired we can take a 10-minute break whenever we feel like it.”

Newsom vetoed a similar bill last year. His rejection of the legislative mandate came after the union had campaigned for him in his successful effort to defeat a recall.

Last year, when Romero asked to meet with Newsom to discuss the voting proposal, he refused. In fact, he vetoed that bill the day after a similar march began, asking him to sign it. The union was so outraged it then marched from the swanky French Laundry restaurant in Napa Valley wine country, where Newsom had held a controversial fundraiser, to his PlumpJack vineyard.

Once again, “we’re at the last step, which is his signature,” Romero said. “We’re trying to paint a picture for him of what farmworkers go through — the intimidation, the threats, losing their jobs. We asked one worker to make a video about it, and she said, ‘No, I can’t. If my employer sees it he’ll fire me.’ We’re trying to relay that to the governor.”

Lourdes Cardenas described how one grower created that fear. “When I was working in the peaches once, some friends came to work with union leaflets,” she remembers. She helped hand them out. “My foreman said, ‘There’s no more work for you.’ I never was able to work with him again. He wanted to scare the other people in the crew by what he did to me.”

One of the starkest examples of worker intimidation occurred in 2013, when one of the world’s largest peach and grape growers, Gerawan Farming, was preparing for a vote to get rid of its obligation to negotiate a contract with the United Farm Workers. The company’s effort began by sending foremen and anti-union workers into the orchards and grape rows, demanding that pickers sign a petition against the union. According to a complaint by the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB), supervisor Sonia Martinez “went row by row and provided the employees in her crew with the signature sheet.”

Supervisors then shut down work entirely, blocked entry to the fields and packing sheds, and handed out the petitions and demanded that workers sign. Agustin Rodriguez, a UFW supporter, told Capital & Main that “they stopped whole crews because of their union activity.”

One worker, Jose Dolores, explained, “People were afraid they’d be fired if they supported the union. I heard it all the time. ‘If I do that they’ll fire me.’” According to another UFW supporter, Severino Salas, “Some of the pro-company workers said that if the company had to sign a contract with the union, it would tear out the grapevines or trees. This threat was coming from the foremen, but they would get other workers to say it.”

On Nov. 5 of that year workers then cast ballots in an election held by the ALRB, in which they had to choose if they were for or against the union. Voting was conducted in the same fields where the intimidation had taken place. When the votes were finally counted, the union lost. Workers no longer had the right to negotiate a union contract.

California’s labor law for farmworkers, the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, prohibits the use of intimidation. Decades of ALRB hearings, however, amply demonstrate that growers’ use of fear to prevent unionization is widespread. Yet the ALRB almost invariably conducts union elections in the growers’ fields, where the fear is often intense.

Workers’ immigration status can increase the fear. According to UFW President Teresa Romero, “The majority of farmworkers are undocumented. When growers see them coming to vote, workers know there will be repercussions.” She adds that when workers are targeted for their union support, it can affect whole families. “Often wives, husbands, brothers, sisters all work for the same farm,” she explains.

March captain Antonio Cortez says that even if the law goes into effect, the union will have to educate thousands of workers about the new system for voting. The march itself is part of that process. Word spreads as laborers see the marchers passing the fields where they’re working, or hear about it from friends.

Cortez believes that the law can potentially inspire a wave of farmworker elections California hasn’t seen since the 1970s. “I think there are two places with a lot of organizing potential,” he explains. “In crops like the strawberries on the coast, the wages are very low, just the minimum, and workers have no benefits. They have very little to lose there. And in crops like the wine grapes, the wages are higher, but the cost of living in liberal areas like Sonoma County is so high that workers can’t survive.”

The campaign for the law can also lead to greater community support for worker organizing, which would help convince growers to sign contracts when workers win elections. “This march is grassroots organizing,” Romero says. “It’s not about money. It’s not about lobbying. It’s about the people who are marching here today and their rights. It’s about respect.”

“I hope the governor is listening,” Cardenas says. “We deserve this law.”

Gov. Newsom’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

As a child, Yolanda Chacón-Serna was part of the historic 1966 farmworker march to Sacramento led by Cesar Chavez.

Paul Boyer, mayor of Farmersville, marches with the workers as the march leaves town.

Lourdes Cardenas, a lifelong farmworker, leads one of the most frequent chants shouted by marchers to keep spirits up: “¡Newsom, escucha, estamos en la lucha!” (“Newsom, listen, we’re ready to fight!”) and “Que queremos? ¡Que se firme la ley!” (“What do we want? That he signs the bill!”)

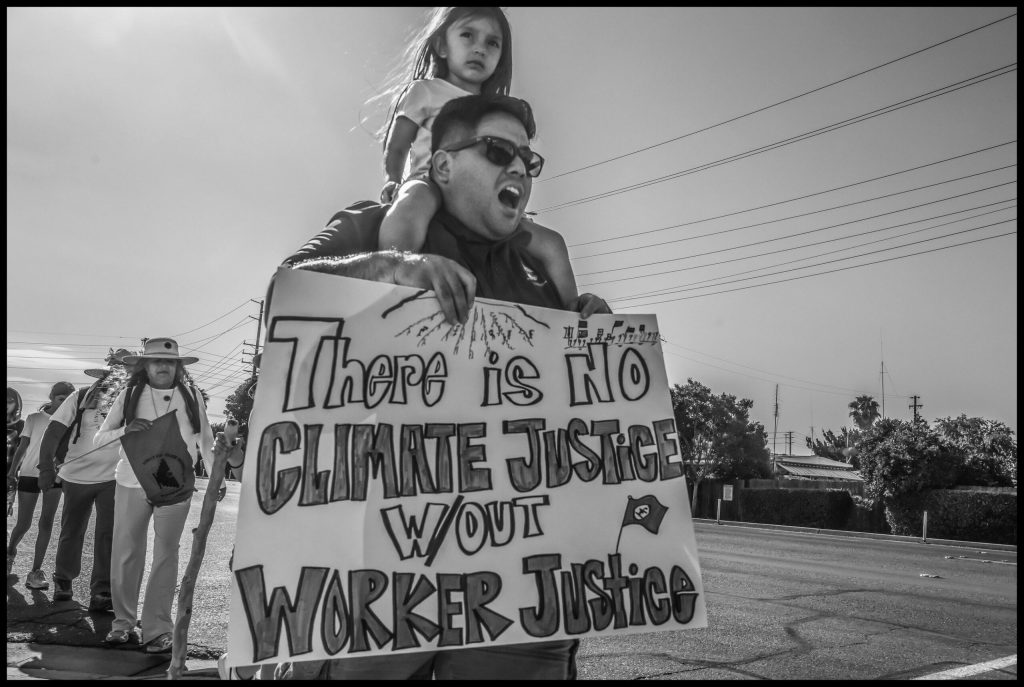

One supporter brings his children and a sign linking farmworkers’ efforts to win healthy living and working conditions with their rights to vote for a union.

Miguel Trujillo carries the banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the Catholic symbol for the struggle of the poor.

All photos by David Bacon.

This story has been updated to note that Gov. Newsom’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Be the first to comment on "California farmworkers march to urge Newsom to sign voting rights bill"