Native daughter channels family history into the Capital’s broader legacy with motorcycles

By Scott Thomas Anderson

The late Italian motorcycle racer Marco Simoncelli once said, “You live more for five minutes going fast on a bike than other people do all their life.”

Simoncelli was an embodiment of that credo; and while he lived by the bike and died by the bike, the tragic coda of his story doesn’t take away from the freewheeling insights that he shared. At least, not for the thousands of avid motorcycle-lovers tearing across the highways of Northern California. Now, a new book is delving into how Sacramento, the River City, evolved into a steel horse-loving town.

Written by the daughter of one of the past time’s early pioneers, “Sacramento Motorcycling: A Capital City Tradition” blows off the dusty tail exhaust of time to reveal a fascinating local heritage. That includes at least two revelations: One is that Sacramento’s high-octane habits around Harleys were originally green-lit by the city’s elite; and the other is that rebellious women riders were part of the saga from the very beginning.

Sharing the dream

Kimberly Reed Edwards was taught to love motorcycles from the time she was old enough to climb on one. Her father, Jim Reed, had opened a small shop for Indian motorcycles in Sacramento in the 1950s. It was a haven for gear-heads anchored at 16th Street and the city’s open rail lines. Reed was such an unabashed enthusiast that, any time a customer made a purchase, he’d eagerly capture the moment by photographing them with their polished chrome stallion.

Eventually, Edwards’ mother became chronically ill, and she remembers her father taking her on long motorcycle rides down the highways and biways along the capital. For father and daughter, it was a form of escape.

“He eventually went into the car business, he never got over motorcycles,” Edwards said of her dad. “We always had several bikes around the house.”

As an adult, Edwards became a writer working in multiple disciplines. She retired from a career in state government in 2012 and began to contemplate penning a labor of love around Sacramento history. She’d heard that organizations like the Fort Sutter Antiques Motorcycle Club of America were trying to preserve the region’s unique riding legacy, which goes back to the first decade of the 20th Century. Edwards had an ideal jumping off point for such a project, because she had inherited her father’s photo archive, which included a slew of local motorcycles customers from the mid-century mark.

Edwards began digging through the newspaper morgue, as well as checking old club ledgers, hobbyist scrapbooks and official state archives. She came to understand that while the seeds of Sacramento’s motorcycle craze started before the Great War, the phenomenon hit new heights in the era of her father’s shop. That’s when G.I.s returning home from World War II were looking for some kind of exhilarating tension-killer. For these young veterans, the Capital City’s motorcycle shops became places to hang out socially, while its organized rides helped them out-run the shadow of a recent catastrophe filling their silences while re-entering American life.

“A lot of the vets had ridden motorcycles in the war; or they had otherwise experienced that same kind of independence,” Edwards explained. “They came back. They knew they were eventually going to get married; but they just kind of wanted to hang out with their buds and re-experience those feelings they had felt, and they comradery they had felt, when they were riding.”

Edwards adds that the motorcycle history that led up to these post-War years had a democratizing effect.

“From the start, it was a sport that cut across social classes,” she stressed. “When cars were first coming in, not many people could afford them. But they could afford motorcycles.”

Founding fathers, deadly races and the engine-revving suffragettes

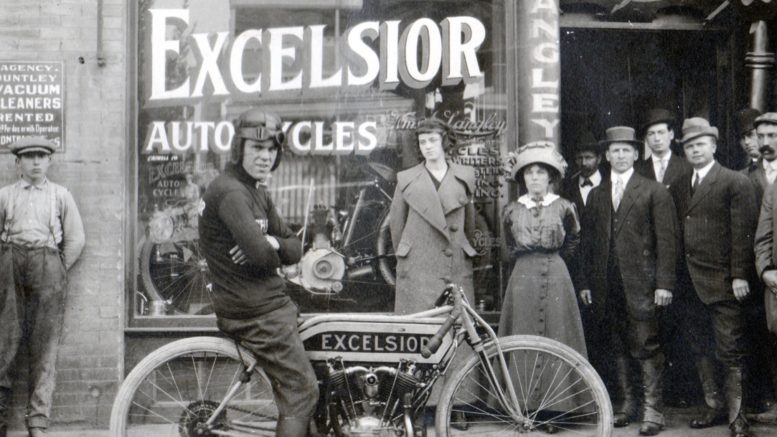

In 1911, there were at least three female members of the Sacramento Motorcycle Club. Nearly a decade before the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote, these groundbreaking bikers were showing off their roadway skills around California’s capital. Perhaps out of some sense of chivalry – or just wanting to class-up their ranks – the club waved the ladies’ official dues.

Scanning the archives, Edwards found photographic evidence that the number of female riders in Sacramento went far beyond that particular trio. The trend was especially pronounced when it came to all of the snapshots of young couples taking sight-seeing rides together on the weekends. And then there were individuals like Bernadette Freitas, who cruised around different neighborhoods on her Knucklehead EL in the 1930s and 40s – the very definition of style and steel-handling elegance.

But the Sacramento motorcycle story has its share of sad moments, too, and Edwards doesn’t shrink from them in her book. One memory the author unearthed is that is that of Scott Orr, the son of an Oak Park doctor who’d become a rising racetrack celebrity by age 19. Orr died in a crash on the San Jose Speedway in 1912. He’s buried in the East Lawn Cemetery. Edwards also details how Sacramento’s earliest motorcycle races were abruptly ended after two different riders from out of town were killed on its track.

Ironically, it was one of Sacramento’s most prominent citizens that got the sporting life around bikes going again.

“We think that motorcycle riding is for fringe groups, but one of the most surprising things I found was that, in Sacramento, the sport started in the power structure,” Edwards explained. “One of the founders of Del Paso Country Club was also one of the prime movers for getting Sacramento’s motorcycle races going again.”

One source that Edwards’ relied on for assistance was Richard Ostrander, Historian Emeritus of the Fort Sutter Antiques Motorcycle Club of America. He’s a Sacramento-based expert who also writes from the British magazine “Greasy Culture.”

“I know where all the skeletons are buried,” Ostrander said this week. “And I knew all of the guys who founded our organization back in 1982.”

Additional help came from longtime Sacramento motorcycle mechanic and writer Mike Blanchard, Sacramento Motorcycle Club historian Ralph Venturino, and SN&R journalist Ken Magri, whose father Armando Magri was a racer who owned the Capital City’s first Harley-Davidson shop. Ostrander says that all of the local bike historians are impressed by what Edwards accomplished. In his view, it’s the kind of book that Sacramento’s community of enthusiasts has spent years hoping for.

“It was the kind of book we always thought we’d write,” Ostrander reflected. “But she was the one who had the writing skills, the research know-how, and determination, to finally make it happen.”

Thank you! Upon the merger of the Sacramento Motorcycle Club and the Capital City Wheelmen back in 1913, the motorcycle club became the “Capital City Motorcycle Club.” It is still around with a clubhouse located in downtown Sacramento at 2414 13th Street. Come check us out some Friday night! Meetings start at 8. Gossip starts at 7:30.