By Scott Thomas Anderson

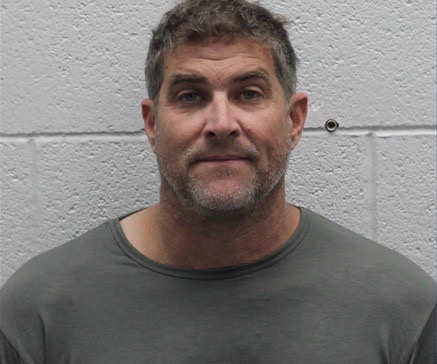

As far as television producers are concerned, the appeal of Dan Serafini has always been his skill with the ladies.

Or his ability to get close to them.

When the retired major league baseball player made his reality TV debut on Bar Rescue, the camera focused in on how Serafini had two fresh-faced female bartenders from his Reno tavern living with him and his wife, Erin: Their names were Winter and Tarah, a self-described “package deal” who the show’s director grabbed footage of knocking back shots at work and partying with bleary-eyed customers.

In the episode, Serafini tells the pair, “You guys are a mess.” Then, with a sly smile on his face, “Settle, because you have to work tonight.”

That is what goes for ‘character development’ in an age of airy depth and memetic desire.

Producers also clearly thought that Erin – Serafini’s new and second wife – was photogenic enough to play well on their monitors, too. They gave her some screen time.

Erin was the daughter of multi-millionaires Gary Spohr and Wendy Wood, a couple who lived in a gorgeous lakeside home just south of Tahoe City. Outsiders can only wonder what they thought of their daughter’s appearance on Bar Rescue. Either way, in the years after it aired, they loaned the Serafini household hundreds of thousands of dollars for various toys and business ventures. But now that Spohr and Wood are dead, it’s not producers from Spike TV who are training cameras on Dan Serafini, it’s veteran reporters for 20/20 and Dateline NBC.

These network personalities have spent weeks flying into Sacramento before making a considerable drive to the sleepy town of Auburn, all to watch a murder trial centering on Dan and Erin Serafini and the pristine shoreline of west Lake Tahoe. But some things never change, and with Serafini, it’s that TV producers are still fixated on his relationship to women: In this case, specifically the ways he’s said to have captivated and controlled a close friend of his wife named Samantha Scott.

There were plenty of other memorable witnesses taking the stand. Jurors heard from another young female bartender who’d worked for Serafini, one who’d seen his steady cocaine use and habit of describing Erin’s parents as “wealthy pieces of shit.” Jurors also met a gold mine worker from central Nevada who’d been with Serafini as he glanced around a desert pit for arsenic rocks and fantasized about acts that surprised even a journeyman hard-hatter. Then there was Jennifer James, who, just days after Spohr and Wood were ambushed by a gunman in their home, watched Serafini showing off a $70K Pontiac GTO he’d just purchased with a loan from Erin’s dad. When the subject of paying Spohr back for the muscle car came up, Serafini off-handedly remarked that he wouldn’t have to worry about that anymore.

These were good witnesses for the mavens of television magic, but producers seemed to agree that the main attraction – the big show – was Samantha Scott. That’s who spurred nonstop whispers.

The manager of some Reno dental offices with a love of horses, Scott’s secret relationship with Serafini was building up to be the trial’s star attraction. When Scott eventually entered the court room, fashionably attired, her straight brown hair parted in the middle, she arguably gave the Media the kind of “other woman” it needed for shows that would pull numbers.

And Scott was also giving the prosecution its kill shot at Serafini.

That wasn’t lost on the former athlete.

Serafini seems to have known that if Scott ever turned on him and became a cooperating witness, he was in danger of spending life in prison for the murder of Gary Spohr and maiming of Wendy Wood (Wood initially survived the shooting but later killed herself, unable to identify her attacker).

Locked in a Placer County holding cell, Serafini understood Scott was charged as a co-conspirator in the Tahoe shootings. Homicide detectives were assembling a cache of photographs, video clips and phone data points to prove that Scott drove Serafini from a gold mine in Crescent Valley, Nevada, to the neighborhood of the Tahoe murder scene, only to soon turn around and chauffeur him back to the desert streets of Elko after Wood and Spohr were left for dead.

It was obvious that if Scott re-aligned herself with authorities, Serafini could strike out for good at his inevitable trial. But, as the aging Big Leaguer sat behind bars, there was suddenly a glimmer of hope. He’d just discovered how to smuggle handwritten letters – known in prison lingo as “jail kites” – to Samantha Scott’s holding cell.

Serafini began penning a dozy.

He would make elements of it deeply romantic. He’d make other parts dazzlingly optimistic. He decided some sections would be lewd and X-rated. And he would seal up all this projected sincerity with an intricate origami rose made of jail toilet paper.

“I have a long reach if anyone fucks with you,” Serafini scrawled in his jail kite. “Stay strong. I know you’re scared. I can’t imagine my life without you. There are so many things I want to do with you, and to you, when this is over.”

‘You should have beat her ass’

One thing that jurors learned right away about the victims in the case, Gary Spohr and Wendy Wood, is that they were emotionally savage when communicating with their daughter, Erin, at times. The main reason that Erin and Samantha Scott bonded was their mutual passion for horse-back riding. Leading up to 2016, Spohr and Wood loaned the Serafinis a big chunk of cash so that Erin could start a ranch and horse-training facility south of Reno. However, when Erin’s parents decided they didn’t like the way she was operating the business, Spohr fired off an email that read, “Erin, your behavior is disgusting – you’ve been terrible to us ever since you were 12.”

Spohr’s message went on to berate Erin’s character in various ways, with him suggesting he’d pull “the nuclear option” on his daughter’s horse-training dream.

That email drew a written response from Dan Serafini, whose method of defending his wife’s honor was telling her parents, “So help me, if Wendy lashes out at me or my family again, you both will regret it … I’m serious about the insults. It better stop … If Erin has been such a bad kid since she was 12, then you should have beat her ass and taught her some respect and appreciation instead of caving in. As far as her talking bad to Wendy, not sure if you have heard the shit that comes out of Wendy’s mouth … Now, let’s all quit the Jerry Springer bullshit.”

Detectives have described the ongoing dynamic between Erin and her husband, and Erin’s parents, as “an up and down relationship.” Sometimes the four would go on trips to exotic destinations together. Other times, Spohr and Wood would be trying to sue Dan Serafini because their daughter dropped out of dental hygiene school, or they’d be telling friends that Erin and Dan saw them as “less than pond scum.”

Justin Infante, a calm-spoken investigator with Placer’s DA Office, was asked to read emails aloud that had been shooting back and forth between the couples.

“You are vicious, belligerent and wasting my time,” Wendy Wood told Dan Serafini in one.

“Fuck both of you,” Gary Spohr said to his daughter in another.

At one point, sitting in her cush Tahoe abode, Wood shot a scolding message to Serafini that said, “You were an exceptional athlete, but your anger got in the way,” which she then followed up with an email to Erin, stating, “Danny resents us, just like his white trash family.”

One of the early witnesses in the trial was Angela Simons, a bartender who’d worked at Serafini’s tavern on and off for a decade. Serafini first hired her before she was legally old enough to serve alcohol, according to her testimony. Simons said she eventually quit because Serafini’s cocaine use and behavior were making her “uncomfortable.” Prosecutor Rick Miller asked her about how Serafini would bad-mouth Spohr and Wood to customers who didn’t even know them. Simons confirmed this was an open topic of conversation with bar regulars: Dan’s in-laws, the “wealthy pieces of shit.”

“Did you express some concerns about coming here today and testifying?” Miller probed at one point.

“A little bit,” Simons said quietly.

“What is your concern?”

“My safety, for one thing,” she replied. “This is kind of intense. It’s a homicide case.”

“You don’t want to be here?”

“Not really.”

“Are you scared of Mr. Serafini?”

“A little bit,” Simons admitted.

“Why?”

“Because of the situation,” she told him, adding she knew Serafini had “a temper.”

Miller asked Simons about a video of the masked assailant who’d shot Spohr and Wood on the night of June 5, 2021. The camera footage showed the individual walking along the shore of Lake Tahoe. Throughout the trial, jurors heard from various witnesses about a distinctive way that Serafini walks, sometimes deemed “the Serafini swagger.” Even Serafini’s older brother, Joseph Serafini – who did not want to help law enforcement – admitted on the stand that the Serafini swagger was real.

“Yeah, all the men in my family walk that way,” Joseph acknowledged. “Just kind of an asshole way of walking.”

However, during his cross-examination, Joseph Serafini said the shooter in the video had a different gait than his brother’s side-hitch.

“It was kind of feminine – maybe gay,” Joseph muttered, unable to suppress a smirk. “The way he flips the wrist. Just kind of flamboyant.”

But when Simons saw the video, she had a different reaction: She saw a pattern of motion she knew well.

Miller asked her, “Did you say to detectives, ‘He always had a certain way of walking: It was kind of like a little limp, but not really’?”

“Yeah.”

The prosecutor directed her to the video.

“It reminded me of Dan,” Simons confirmed.

“Is it hard for you to say that?”

“A little bit.”

“Why?”

“Because” Simons’ voice began cracking. She pushed a tear away from her eye. “It’s scary,” she said.

Driving through an open gold mine with hostile wishes and arsenic dreams

In the spring of 2021, Serafini had come a long way from his days of traveling the country as an MLB player and getting offers to pitch around the world. He’d owned a bar in Nevada’s “biggest little city.” He’d had a brief highlight on reality television. But now the journey had led him down a hole – literally. Serafini found himself working at an industrial gold mine in the Silver State’s Crescent Valley. It was an outcome few would have predicted when Serafini, the Pride of San Bruno, California, was first drafted out of the same high school that produced Tom Brady and Barry Bonds. Back then, signed Dan Serafini baseball cards were being handed out to all the teens in the neighborhood.

Two careers later, Serafini was laboring in a desert mining operation.

One afternoon, he was in the passenger seat of a truck while his supervisor, Eric Buner, was behind the wheel. Serafini’s cell phone rang. Buner watched him pick up, engage in a brief conversation, then throw his phone against the dashboard. Noticing that his employee was agitated, Buner asked what the problem was. Several years later, Buner found himself called to testify about the answer 390 miles away in an Auburn courtroom.

“I remember exactly where we were,” Buner said on the stand. “I remember it pretty vividly. He said, ‘I’m going to kill these mother f—. I won’t say the word, but you get the gist.”

One of Serafini’s attorneys, David Dratman, tried to undermine Buner’s account by demanding to know why he didn’t go to HR or the police.

“It was just a conversation between two dudes,” Buner remarked, unfazed, noting that he thought Serafini was simply “blowing off steam.”

“Weren’t you, yourself, having some relationship problems at the time?” Dratman pressed.

“Yeah, I was going through some stuff,” Buner responded before clarifying that it wasn’t on the level of Serafini’s issues.

“I mean, when you’re looking for arsenic rocks at work to put down a well, there’s probably something going on,” Buner observed. “I remember him being severely angry as he proceeded to talk about putting an arsenic rock down [his in-law’s] well … I told the detectives he talked about different ways of killing them. Burning their boat. Putting an arsenic rock down their well.”

Slipping into jacuzzis, testing gun silencers and staging car accidents

Erin and Samantha Scott were women who liked traveling together, particularly to far-flung horse events. Scott grew accustomed to spending nights with Erin and her kids in RVs and hotel rooms. Occasionally, Dan Serafini would tag along. So, in the spring of 2021, it wasn’t entirely surprising when Serafini informed Scott he’d soon need a ride from Elko, Nevada, to north Lake Tahoe. He didn’t want her to tell anyone about the trip, Scott testified at the trial. She said Serafini also insisted on removing any identifiable stickers from her gold Subaru and getting it wrapped in a different color before they left. Serafini would pay for everything.

When Miller, the prosecutor, asked if such precautions had seemed unsettling at the time, Scott answered they didn’t because Serafini was indicating the mission was all about scoring a giant package of cocaine along the lake. The only thing that seemed off, she clarified, was that Serafini had briefly floated the idea of mixing a little insurance fraud into their mission by reporting the Subaru stolen and Scott keeping the payout. Scott wasn’t comfortable with that. She said Serafini then offered to pay her $5,000 for the ride, so long as she changed the look of her vehicle and kept her cell phone powered-down.

None of these memories Scott shared were surprising to the TV producers looking on in the courtroom. Miller had telegraphed much of this story in his opening arguments. He’d also spent weeks showing jurors evidence of that fateful sojourn from Elko to Tahoe, including hotel videos of Scott and Serafini meeting in northeast Nevada, forensic tracking of Scott’s cell phone from Serafini’s mining job to the victims’ neighborhood, and still-frame images of Scott waiting for hours at a nearby resort during the time of shootings. What did come as a surprise to many in the audience was the revelation that Scott and Serafini hadn’t begun their torrid affair just yet.

One way to read Scott’s testimony is that the seeds of it began the night before the bloodshed.

She recalled her and Serafini snorting lines of cocaine at the hotel before heading out to get sauced at Elko’s bars. Scott remembered that, as Serafini kept tossing drinks back, he started opening up about his relationship with Erin.

“He had told me this wasn’t really the life he had in mind,” Scott recalled. “He had already had two kids from a previous marriage; and when him and Erin originally got together, they both didn’t want more … And so, when they had more kids, even though he was happy to have them, it wasn’t his plan.”

“Was it a shock to hear him go into that subject matter?” Miller pondered.

“Yes,” Scott admitted. “Just from how I’d known him and Erin, previously, it wasn’t something I would have seen … He had said that he wanted to leave when the kids were a little older and they would understand that.”

According to Scott’s telling, she and Serafini eventually left the bars and went back to their hotel room – one that had its own jacuzzi. That’s when she says Serafini slipped into its broiling bubbles naked. Scott decided to join him in her bra and underwear.

“Was that strange?” Miller asked.

“Yes,” Scott decided. “But it was still platonic – friendly. I’d known him three years.”

Scott said at some point she went to sleep. When she awoke, Serafini had driven 30 minutes away to his gold mining job in Crescent Valley. She knew that he was waiting for her to pick him up. It was time for their journey. She rolled up to Serafini’s trailer at the mine in her Subaru. He jumped in with a backpack, making sure to leave his cell phone behind. As they drove out of the valley, Scott testified, Serafini made an unexpected request.

“He asked me to stop and pull over for a moment,” she told the prosecutor. “I did, and he took a gun out of the bag and shot it into one of the sand hills, saying he was just checking to make sure it was working … The gun had a PVC pipe on it … He said he had made it in the shop, and it was to act as a silencer.”

Miller stood, waiting for a half-beat. “Was this strange to you?”

“In some ways, yes,” Scott answered. “The fact that he was shooting to make sure it worked, yes. The fact that he had a gun, no. I’ve frequently seen guns with him in cars and RVs.”

“How about shooting into the sand,” Miller pin-pointed. “Was that strange?”

“Yeah,” Scott agreed. “I mean, he had said that he’d just made the PVC attachment for it, and so he wanted to make sure it worked.”

Scott then described a nearly five-hour drive to the shoreline of Tahoe where Spohr and Wood lived. She remembered waiting hours while Serafini was on his supposed cocaine mission. When he finally returned at night, she said, he ordered her to make haste for Crescent Valley. As they were driving, Scott testified, she broke the news that she’d accidently left her cell phone on. Serafini didn’t get mad, she insisted, but did start throwing items from his backpack out the window. She recalled hearing the sound of him breaking his pistol and silencer down before chucking those into the darkness.

Miller asked what was going through her mind.

“Throwing things out the window was strange,” Scott responded. “I thought littering like that was strange.”

“When court took a recess, you were crying,” Miller mentioned. “Why?”

“I feel guilt about being involved in this,” Scott muttered. “It’s just a lot.”

But when did that guilt start? That’s what Miller wanted to know next.

Scott admitted that, the next day, when hearing about Spohr and Wood being shot, she briefly convinced herself that their trek to the area was just a coincidence. Scott didn’t tell Erin about driving her husband to the vicinity of the crime scene. But Scott’s compartmentalization could only last so long. She testified that, even though she’d removed all the stickers from her Subaru, Serafini began obsessing over the fact that the vehicle had a recognizable dent in its bumper. He told Scott to meet him in Reno at a dirt pull-out near a Jimmy John’s.

“He backed up into my tailgate to create more damage than was there,” Scott told the jury. “He said he would pay for it.”

Scott said she knew then that Serafini was worried about more than catching a drug charge.

Miller wanted to know why she didn’t voice that concern to anyone.

“I’m not really the person who gets guided by that kind of questioning,” Scott replied.

“Is that how you were with Erin?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Is that how you were with Dan?”

“Yes.”

Miller lowered his shoulders and voice a little: “Is that kind of how you’ve been your whole life?”

Scott nodded. “Yes.”

A wife reacts to the ‘queen for a day’ and her husband’s jail kites to that witness

In the weeks following the Tahoe shootings, Serafini and Scott started sexting each other, apparently reliving some passionate escapades. Again, investigator Justin Infante – the very picture of professionalism – had the unenviable tasks of reading their highly explicit messages to a jury of strangers, many of which delved into hook-up hunger, fallacious promises and talk of choking. Serafini had also texted Scott a slew of porn links, though Infante managed to simply reference those without reading aloud what hyper-hedonistic corners of the internet they’d come from.

“And then there’s a link,” Infante would note in neutral tone.

The carnal communications were so voluminous that defense attorney David Dratman seemed lost in their contents at one point, offering reporters and jurors the most bafflingly suggestive yet non-contextualized double-punch of questions in the entire trial: It happened while he was cross-examining Scott.

“For Halloween, did you dress as Elvira one year?” Dratman asked her on the stand.

Scott’s eyes narrowed. “No.”

“Did you ever know Mr. Serafini to dress as the Big Bad Wolf?” Dratman went on.

Scott stared at him. “No.”

One juror almost doubled over with silent laughter.

After a pause, Dratman said, “Your Honor, this would be a good time to take a break so I can review my notes.”

But the erotic imaginings continued between Serafini and Scott, even once they were in custody. That became undeniable when prosecutors approached Scott in January of 2025 with an offer known as “Queen for a Day.” Essentially, it allowed Scott to engage in an hours-long interview with detectives, but nothing she said in it could ever be used against her in court. According to Scott, that’s when she came clean about everything.

“Who did you lie for?” Miller asked her in front of the jury.

“Dan.”

The prosecutor brought up a jail kite she’d written to Serafini, one in which she’d promised to be his “ride or die.”

“What did you mean by that when you wrote it to him?” Miller pressed.

“I meant it as, ‘I’ve got your back on this,’” Scott said. “I will continue to tell my lies.”

“And what was your hope by doing that?”

“That we would both be going home.”

Miller softened his stance. “Is that still your hope?”

“Sometimes, yes.”

“For him, even?”

“Yes.”

The courtroom was silent for a moment.

During cross-examination, Dratman was also curious about the jail kites.

“You were asked about that ‘ride or die’ quote,” the defense attorney began. “That’s actually from a song?”

“Yes,” Scott said, alluding to a bass-heavy EDM tune by The Knocks featuring Foster the People.

“And you actually told [Dan] that whole song,” Dratman questioned. “You have it memorized?”

“It’s not the whole song, it’s just a part,” Scott came back quietly. “‘Ride or die, yeah, we’re going to fly.’”

Throughout the affair with Serafini, Scott maintained her close friendship with Erin. In fact, the women had stayed so close that Erin offered to pay for Scott to accompany their family on a vacation to the Orcas Islands, getting Scott a plane ticket and a place to stay. Erin also met up with Scott in Tijuana, Mexico, while both were having “procedures.” In Scott’s case, it was surgery that involved weight loss – and Erin and Dan Serafini paid for it.

Miller decided that the jurors needed to hear from Erin. Two days before the prosecution rested, he called the victims’ daughter to the stand.

TV producers weren’t able to film or photograph Erin as she came in, seemingly at ease in a chic blue strapless jumpsuit over a white button-down dress shirt. She looked leaner than she had in Bar Rescue, and her full hair was a natural auburn color rather than the fire-iron red it had been during the show. After being asked for hours about the constant arguments with Spohr and Wood, and the sizable inheritance Erin stood to gain while married to Serafini, Miller drew her attention to the day that a Placer County Sheriff’s detective first told her Scott’s cell phone had been detected near the crime scene.

“Did that concern you?” Miller urged.

Erin shook her head. “No.”

“Why?”

“I believe she told me that she’d just gone up there to hang out,” Erin explained, “which was a super common practice. It’s Tahoe. We’d go up there all the time with the dogs and my kids.”

Miller and Erin began a frustrated, drawn-out exchange in the courtroom about why Erin didn’t do more to investigate what exactly Scott was doing near her parents’ house when they were shot.

“I would never assume she had anything to do with it,” Erin stressed. “By the time I found out there were pictures and video, she was incarcerated.”

Meanwhile, Erin’s friends in the audience kept grumbling under their breath that Miller was “an asshole,” repeatedly leaning over to stress to the author of this story that they could be quoted on that.

But Erin projected confidence during the questioning. Throughout her testimony, Erin had been a lively and energetic witness. She appeared to have on-lookers in the room fixated, especially when claiming that she didn’t believe the masked assailant filmed entering her parents’ house was her husband. Erin drew smiles while sharing an anecdote about her late dad. She was precise when clarifying what her understanding of Wood and Spohr’s will was. Erin had even stopped in the courtroom hallway on a break to congratulate a media sketch artist on how “cool” the chalk renderings of her looked.

In the coming days, Erin would arrive in Auburn dressed to the nines and lead a group of supporters through the old court’s packed corridors, ultimately sitting just 12 feet away from Serafini’s left shoulder at the defendant’s table – and in a completely different part of the viewing gallery than her sister, Adrienne, who is currently suing her for wrongful death regarding their parents (Adrienne thinks Erin was involved). In that moment, Erin would keep her chin up as Miller delivered a surgically devastating take-down of Serafini and his defense during closing arguments.

But late into the afternoon of her second day of testifying, with Miller’s drum beat about the various deceptions that her husband and her best friend carried on between 2021 and 2022 bearing down on her, Erin’s vivacious aura looked like it was starting to dissipate. Her answers got quieter and less responsive.

Referencing the way that Erin and Serafini had paid for Scott’s cosmetic procedure in Mexico, the prosecutor inquired, “Did you think Samantha Scott wanted to be like you?”

“A little bit, maybe,” Erin said quietly.

Miller stood up. “Did you tell Detective Mattison that she idolized your husband, and wanted to be you?”

“I think she had a little crush on him,” Erin muttered.

“Did you tell detectives that Samantha was like a lost, wounded puppy?” Miller continued.

“I might have,” Erin acknowledged in a low voice. “She always wanted to be around us.”

After falling silent for a second, Erin added, without any prompting, “I mean, she eventually started sleeping with my husband.”

Miller took a sober, understanding stance: “Did you trust Samantha Scott?”

Erin’s expression deadened. “Umm,” she cleared her throat, “I don’t think I ever trust anyone wholeheartedly.”

Later, at the very moment the trial’s closing arguments were ending, a young couple stood taking their vows in front of the courthouse.

*UPDATE: On Monday afternoon, July 14, a jury found Dan Serafini guilty of the First Degree Murder of Gary Spohr, with the special circumstances lying in wait, and guilty of the attempted murder of Wendy Wood, as well as home burglary. His sentencing is scheduled for mid-August. Randi Pechacek contributed to this story. Scott Thomas Anderson is also the writer and producer of the documentary true crime podcast series, ‘Trace of the Devastation.’

Great piece-very well written. Thanks SNR and keep up the amazing work!

since I was required to sit and listen as I served. Slow me to tell you that you captured this story like you were sitting in the box with us. I look forward to your story after Friday. The appeal gave us an insight into Dan’s thoughts and lies. I am appreciative that the judge saw threw it. Thank you for accurately portraying this trial.