By Marie-Elena Schembri

You might not think a tipi, skateboarding, basketball and Casper the Friendly Ghost have much in common, but that’s because you haven’t seen Indigenous artist Spencer Keeton Cunningham’s new exhibit, “Decolonization,” at Verge Center for the Arts yet. Colorful, quirky and impactful, this exhibit confronts environmental issues, Indigenous rights and the damaging effects of colonization through the lens of the artist’s personal history.

A member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in northern Washington, Cunningham considers the reservation his home despite having lived in numerous places, including San Francisco (where he attended the San Francisco Art Institute), Washington, Oregon, Las Vegas, Texas and abroad. Cunningham’s paintings are in the permanent collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Berkeley Art Museum and Sacramento’s Crocker Art Museum. He was a featured artist at the Fog Design+Art Fair at Fort Mason last month.

For “Decolonization,” he has assembled a massive collection of works, impressive in both number and scale. Each gargantuan canvas — some as large as 15-by-20 feet — was stretched and installed (and some painted) on-site by the artist. Sculptures, photography and multimedia installations accompany the paintings, creating an immersive experience within the Verge’s walls.

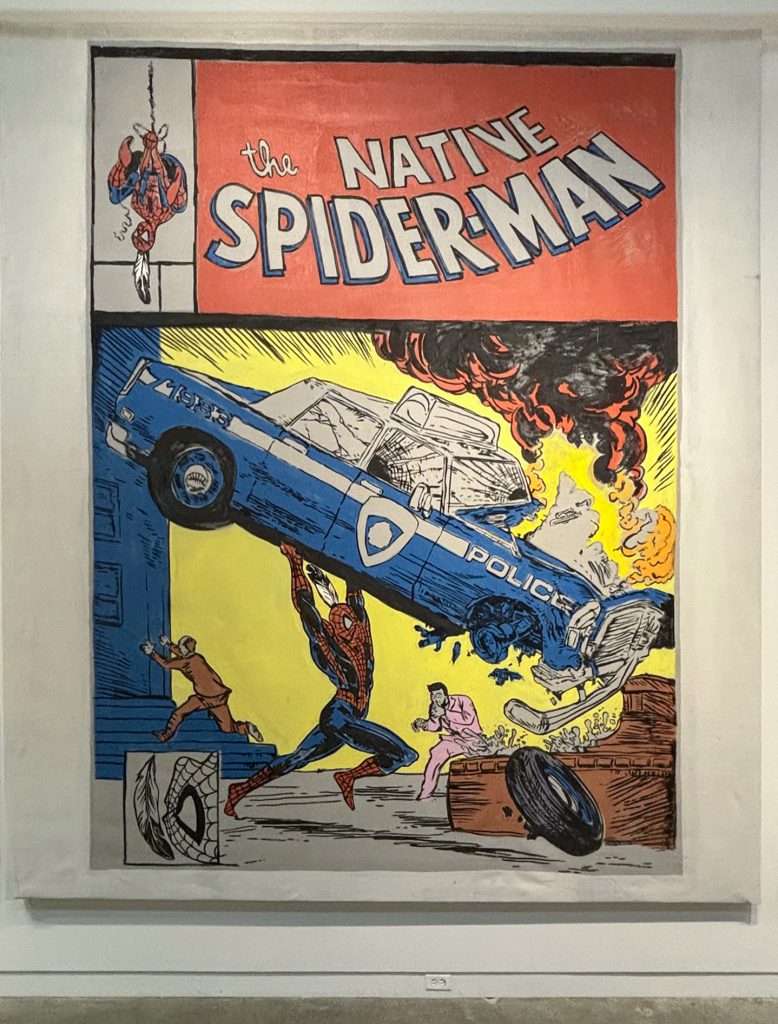

Cunningham’s distinct visual language incorporates a diverse use of mediums and techniques, sometimes painted in a street art style or featuring cartoonish scenes and dense graphic iconography. Cunningham uses humor to address the many examples of racist stereotypes and cultural appropriation used in commercial branding and popular culture. Recognizable characters and logos are paired with hints of deeper subtext. Despite the visually stimulating, colorful style of Cunningham’s art, the works address heavy topics, from missing and murdered Indigenous women to personal loss and grief.

One painting, “Casper the Friendly Small Pox Ghost,” tells the story of the destruction of Indigenous culture through colonization. The central figure — a purple ghost-like form wearing a cement feather and a look of bewilderment and covered in bright red dots — represents smallpox, a virus brought to America by European settlers, decimating Indigenous communities.

Cunningham’s ghost figure also alludes to the way Indigenous people “remain unseen in the education systems of this land as well as every other system,” according to the artist. He uses gold paint and a snake made of smoke among other symbols to represent the greedy pursuit of gold that created “the first zombies,” as he describes early colonizers. A river runs red with blood, symbolic of the destruction that continues to ravage the environment and impact the lives of Indigenous people today.

Cunningham has experienced this firsthand on his reservation, where the Grand Coulee Dam has cut off the natural supply of salmon and water from nearby rivers since its construction in 1942.

“A way of life was ended and the ground — sacred gathering grounds of seeds, roots — everything above ground was flooded,” Cunningham said. “To this day, you can come visit my reservation and on one side of the river you’ll find no water.”

Visitors can find nods to reservation life and native culture throughout the show while personal touches like an installation of a basketball hoop and Cunningham’s middle school locker, rescued from the now defunct school building. The show is also dedicated to Cunningham’s late friend and collaborator, Richard Bluecloud Castenada, who died from a rare bone cancer last year. Castenada and Cunningham were part of a student group that formed the Indigenous Arts Coalition at the San Francisco Art Institute. “He was an incredible Indigenous photographer, artist and a human,” Cunningham said.

An interactive tribute to Castenada sits in the center of the exhibit. A tipi encloses a small space intended for reflection, with a digital typewriter and tape recorder where visitors can share their thoughts about the exhibit. Photographs of Castenada taken by Indigenous Arts Coalition member Nizhoni Ellenwood, and other relics of their time together, add to “one of the most emotionally impactful shows that we’ve produced in a while,” according to Verge director Liv Moe.

In true Cunningham style, a skateboard ramp is poised nearby; another detail that references the artist’s personal life and the culture that shaped him.

Other artist collaborations in the exhibition include a large self-portrait of Castenada re-printed by Randall Langdeau, which sits under a coyote Cunningham created out of hundreds of blue and yellow American Spirit cigarette cartons that had belonged to Castenada. Japanese rapper Shing02 and Los Angeles-based artist Mario Ayala also collaborated on works with Cunningham.

Through bold visuals and a mix of traditional and non-traditional mediums, this powerful exhibit offers unapologetic social commentary and a deeply personal look into the life of an Indigenous artist.

“These paintings are a snapshot of my life and the world I’ve created up to this point with my art practice. I welcome people into that world and hopefully, it’s an enjoyable experience,” Cunningham said, adding that the show’s primary purpose is to “help decolonize the minds of the viewers who see it.”

“Decolonization” is on view at Verge Center for the Arts through March 23. A panel conversation with the artist will be held prior to the exhibit closing, date to be announced. For more information, contact Verge Center for the Arts.

This story was funded by the City of Sacramento’s Arts and Creative Economy Journalism Grant to Solving Sacramento. Following our journalism code of ethics and protocols, the city had no editorial influence over this story and no city official reviewed this story before it was published. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, Capital Public Radio, Outword, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review, Sacramento Observer and Univision 19. Sign up for our “Sac Art Pulse” newsletter here.

Be the first to comment on "Indigenous artist Spencer Keeton Cunningham combines personal narratives, social commentary in ‘Decolonization’"