By Scott Thomas Anderson

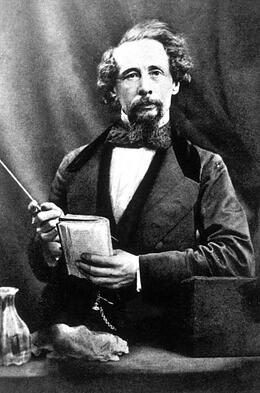

Charles Dickens never made it west of Buffalo, New York, during his longest visit to America in 1867; though, by then, his tale of a holiday haunting in London had been rattling its chains in the psyches of California pioneers for decades.

Even though Dickens didn’t see the Golden State, his yuletide meditation on poverty and social abandonment remained relevant from the streets of Sacramento to the docks of San Francisco throughout his lifetime – and for generations to come. Now, in December of 2022, a drive along Broadway Avenue in the Capital City, or walk through the Bay Area’s Tenderloin District, suggests that the mindset Dickens was battling against with “A Christmas Carol” is still present in our corporate boardrooms and halls government. Maybe even more so than it was during California’s Gilded Age.

In January of 1848, five years after Dickens penned “A Christmas Carol,” a Mormon lumber worker named James Marshal notices a strange glimmering in a creek just north of Placerville It wasn’t long before Marshall was making his way through a rainstorm to an adobe fort in Sacramento, intent on telling his boss, John Sutter, what lay under those cold January waters. According to Sutter’s journal, when Marshall first approached him inside the outpost with a small object wrapped in a rag, he looked around and cautioned, “Lock the door.”

On the other side of the world, Dickens was getting ready to publish “The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain,” his last yarn set in Christmastime. By then, Dickens was a reliable best-seller on both continents. Part of the reason for his stature was the success of an earlier meditation on disembodied spirits during the holidays – his saga of Ebenezer Scrooge.

Time Magazine writer John Broich has observed that Dickens began conjuring the characters of Scrooge, Tiny Tim and the temporal ghosts of a Christmas in 1843 after reading a government report about child working conditions across Britain. Dickens was dismayed to learn that children as young as eight were becoming disabled working in factories or on coal wagons. He set out to use the best of his imaginative powers to create an unforgettable literary statement, one which sought to draw attention to poverty and social injustice, and which countered the writings of Harriet Martineau, a social theorist of the time.

It was Martineau’s writing that popularized the theories of economist Thomas Malthus. In the early 19th century, Malthus published his treatise arguing that a lack of population control would always lead to wide-spread poverty, suffering and self-disintegration, as human were – in his view – inherently driven to reproduce on a scale that overran the resources they had to survive on. This Malthusian calculus had a huge influence on Charles Darwin’s model for understanding the natural world or what came to be known as its ‘survival of the fittest’ mechanism propelling evolutionary change. For Darwin, however, this was a broad scientific observation but definitely not something governments should apply to policies on how to deal with famine, poverty or the reality of unhealthy children. Some of Darwin and Dickens’ contemporaries felt otherwise. Over time, the idea of “social Darwinism” took hold, helping to justify the government’s decision-making on everything from consigning the poor to workhouses and abandoning child labor protections, to the food distribution framework that caused one million deaths in Ireland during the Great Famine. Malthus was an academic, but his theory was translated for upper-class London, and given to popular culture, but the writing talents of Harriet Martineau.

In essence, the best person to fight that effect was another popular writer. Even before publishing “A Christmas Carol,” Dickens had already started down this path by writing “Oliver Twist” and “Nicholas Nickleby,” which humanized children soldiering through tough, unstable lives. However, the Christmas tale he molded in 1843 out of manger references and the supernatural solstice glow became its own feat of magic.

In early December of 2022, an Ebenezer Scrooge meme began circulating around the internet with the caption: “Unions – because the chance of three ghosts visiting your boss to make him do the right thing is unreasonably slim.” In a way, the meme speaks to the amazing force “A Christmas Carol” has had in the western mindset for almost 180 years. In another respect, it also suggests that many people haven’t actually read Dickens’ novella, but rather know the story from an endless stream of film and cartoon adaptations. That’s because it is not the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present or Future who make the most-persuasive case against elevating greed and self-interest above human empathy. Rather, it’s an earlier specter visiting Scrooge on Christmas Eve, the tortured apparition of his dead business partner and secret-sharer, Jacob Marely. The trio of ghosts who follow are just reflections of Scrooge’s own fears and memories. But having to face Marley equals a shattering confrontation – and a chilling one.

“Scrooge had often heard it said that Marley had no bowels, but he had never believed it until now,” the story tells us. “No, nor did he believe it even now. Though he looked the phantom through and through, and saw it standing before him; though he felt the chilling influence of its death-cold eyes; and marked the very texture of the folded kerchief bound about its head and chin.”

As the spirit’s disturbing contours take form, Scrooge tries to rationalize the experience only to be brought to his knees in blood-curling terror. With his reality broken, Scrooge is prepared to hear the warning of this ghost, which turns out to be a mournful testament to the chains guilt and locks of regret wrapping Marley’s wandering shade.

“I wear the chain I forged in life,” Marley laments. “I made it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it.”

The chains, Marley goes on, represent the weight of an existence wasted on avarice. At first, it’s not a message that Scrooge is entirely comprehending.

“But you were always a good man of business, Jacob,” Scrooge replies.

The response Dickens put in Marley’s rotting mouth has remained piercing for over a century.

“‘Business!’ cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. ‘Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business! … At this time of the rolling year I suffer most. Why did I walk through crowds of fellow-beings with my eyes turned down, and never raise them to that blessed Star which led the Wise Men to a poor abode? Were there no poor homes to which its light would have conducted me!’”

These words were written just three years after John Sutter, across an ocean and a continent, finished building his fortress in Sacramento. Sutter was very much in the mold of what Jacob Marley had been in life: he surveyed Virgin California’s vast beauty and saw the potential for unlimited wealth; whatever the dire consequences his pursuit of riches had for the Mexican and tribal peoples already living there.

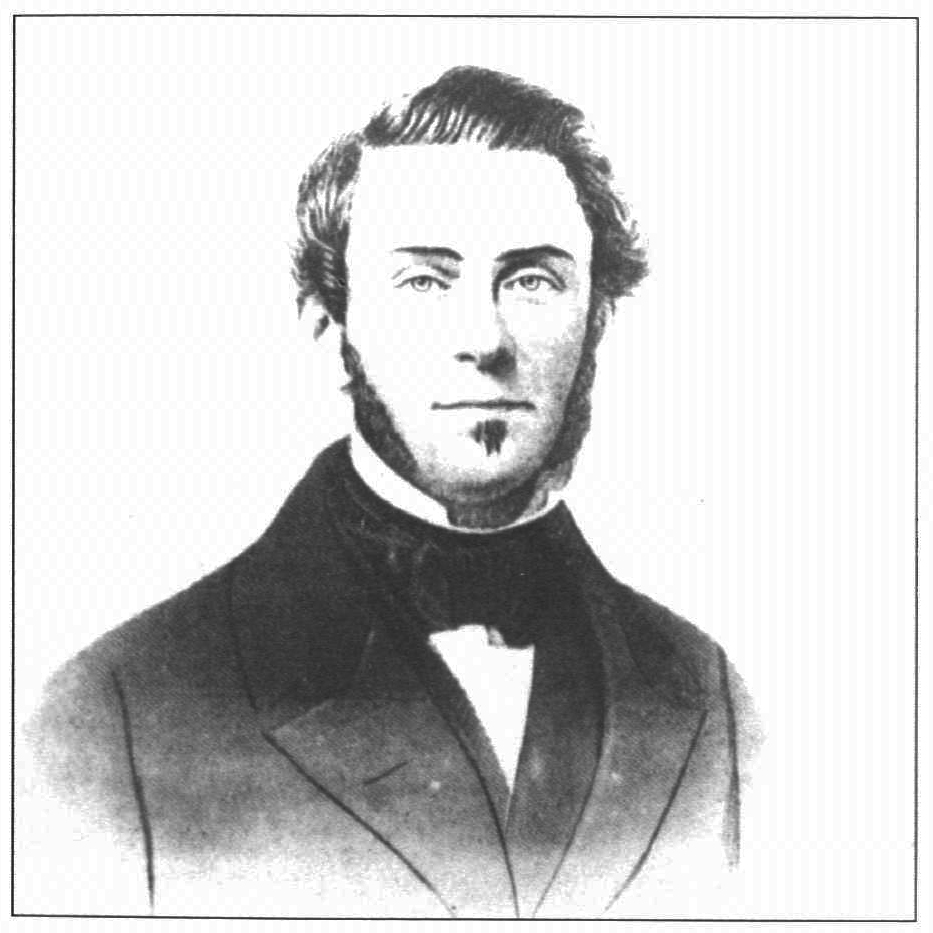

While Sutter considered himself an economic visionary, he seems to have been stumped on how to handle the discovery of gold at his mill. Due to his hesitation, some historians argue he wasn’t the one who truly launched the California Gold Rush. Rather, they suggest, it was an Irish-American Mormon and itinerate journalist named Sam Brannan.

Brannan was operating a store for Californios near Sutter’s Fort when Marshall made his secret discovery. When Brannan caught wind of it, he had the foresight to predict that the greatest fortunes to be made in the West wouldn’t come from mining gold but from capitalizing on hordes of hopeful gold miners. So, it was Brannon who took a few flakes of glitter to San Francisco and quickly leveraged his newspaper connections to create an international headline. As argonauts from Cornwall to Argentina flooded into the Sacramento Valley, Brannan’s plan worked to perfection. Sutter’s own business empire eventually collapsed and Marshall himself died without a cent to his name; yet by the time Charles Dickens made his final trip to America, Brannan was California’s first certified millionaire.

Dickens’s tour of the U.S. happened when entire cities in Virginia, Georgia and the Carolinas were devastated by the Civil War. Whether by design or not, the author’s speaking tour avoided seeing any of that wreckage: He never traveled south of Washington D.C.

But the real economic pain for the land was still to come. Six years after Dicken’s visit, with financial scandals and flawed speculation wreaking havoc on the monetary system, America spiraled into what became known as “the Long Depression.” The strife and deprivations that hit Northern California were well-documented by Henry George’s book of the time, ‘Progress and Poverty.’ From the ashes of this extreme instability rose the America’s ‘robber barons,’ single-minded titans of industry who reached their tentacles around most of the nation’s wealth. Yet, for all their faults and monopolies, some of the robber barons like Andrew Carnegie – born into hardship in Scotland nine years before “A Christmas Carol” was published– had a very different view of social responsibility than England’s monied class had demonstrated when the poor laws were being championed. And this was especially true in Sacramento and San Francisco where the Big Four railroad bosses were building their mansions along the avenues. By then, what could be called a ‘Dickensian’ ethos was in the air. Charles Crocker, Leland Stanford and their families adhered to it, becoming the dominate philanthropists of the era. Together, they founded universities, public library systems and art museums for all and wrote countless checks for benevolent societies.

The opulent Victorian mansion that still stands at 800 N Street in Sacramento speaks to those ideals. The first shell of it was built by a prosperous Gold Rush merchant in 1856. At the outset of the Civil War, it was purchased by Leland Stanford, who renovated it into an ornate gem of Second Empire architecture. In 1900, the railroad builder’s widow, Jane Stanford, deeded the mansion over to the Catholic Diocese of Sacramento, along with a large endowment of money, specifically for the “nurture, care and maintenance of homeless children.” It went on to serve as a children’s home for nearly 90 years. No matter how many riches a small group of individuals in Northern California amassed during the Long Depression, the Malthusian mindset that Dickens had waged his creative war on was nowhere to be seen with them. The zeitgeist around whether crippling poverty was acceptable, especially for kids, had changed. “A Christmas Carol” was one writer’s greatest achievement on the way to seeing that realization come to our chilly winter nights.

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the host of the ‘Drinkers with Writing Problems’ podcast.

Be the first to comment on "Christmas ghosts, the California Gold Rush and hard times in Victorian Sacramento"