The waning days of the Gold Rush were overshadowed by tense journalistic standoffs around the Civil War

In 1861, California’s Capital region was far from the blood-flowing battlefields of Civil War; yet mighty pens clashed over the struggle nonetheless, especially in Amador County, where rival newspapers fought for the permanent soul of that community. It was a confrontation in which printed words were sharper than cavalry sabers – and ink ran in the spirit of blood.

The excitement that followed gold’s discovery in Coloma in 1849 drew wide-eyed dreamers from both the northern and southern states. That meant that when the first shots of the Civil War were fired 12 years later, political loyalties were bitterly divided across California. Despite its government sticking with the Union, countless mining towns ended up with two competing newspapers, one staunchly loyal to the federals, the other tacitly aligned with the confederates.

This created breeding grounds for personal violence between reporters.

In Nevada County, a war of words on the opinion page led the editor of The Grass Valley National to ruthlessly beat the publisher of The Grass Valley Union on one occasion, and draw his pistol on the newspaper’s new editor on another.

Ninety miles to the south, in Amador, similar escalations were beginning to envelope all of its towns.

It started with the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. One man who was breathlessly following headlines in Jackson was William McMullen, the publisher of The Amador Dispatch. McMullen felt so patriotic about Abraham Lincoln’s cause that he saddled up his horse, joined the Union Army, and rode off to be part of the long, tragic confrontation. Given where McMullen’s heart was, some Jacksonians found it curious that the two men he’d left in charge of The Dispatch were George Payne of Virginia, and William Penry of Mississippi.

Readers would soon discover that both were fiercely allied with their Southern friends and families. Penry and Payne were among thousands who were still bitter that California had not been made a slave state when it came into the Union. Such rage-criers were known throughout the gold country as copperheads. Penry eventually hired a new editor; a slavery-celebrating firebrand from Mississippi named L.P. Hall. The three men created a Johnny Reb triad in the newsroom– and The Dispatch was transformed into an unapologetic rallying point for Confederate sympathizers.

In one editorial, The Dispatch described President Lincoln as “a self-confessed perjurer,” a “buffoon,” a “vulgar joker” a “spiritualist” and, worst of all in the minds of Penry and Hall, “an abolitionist” who believed Black Americans deserved liberation. Today, such words spark so much rage that it staggers the mind to imagine a local newspaper ever publishing them; but even in the 1860s, Amador County had another news agency that was steadily offended: The Amador Ledger was as supportive of Lincoln and a Northern victory as The Dispatch was of slavery and Southern insurrection. The Ledger’s publisher, Tom Springer, wasted no time in attacking his ink-smudged counter-parts.

Springer wrote columns that took personal aim at the men steering The Dispatch. He referred to Penry as a rather “unsophisticated young man,” before announcing that Hall was a shifty propagandist who “palms off his copperhead balderdash as the productions of the simpletons who ostensibly own the concern.”

The men at The Dispatch didn’t take the insults lying down. They quickly fired back columns declaring that The Ledger “spreads abolitionist filth on white paper,” adding that it was written “by pap-sucking scribblers.”

The two newspapers continued to fling mud at one another right up until Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, 1865. When the Derringer came out in Ford’s Theatre that night, thousands in Amador – particularly those who worked at The Ledger – were devastated by the loss of their Commander in Chief.

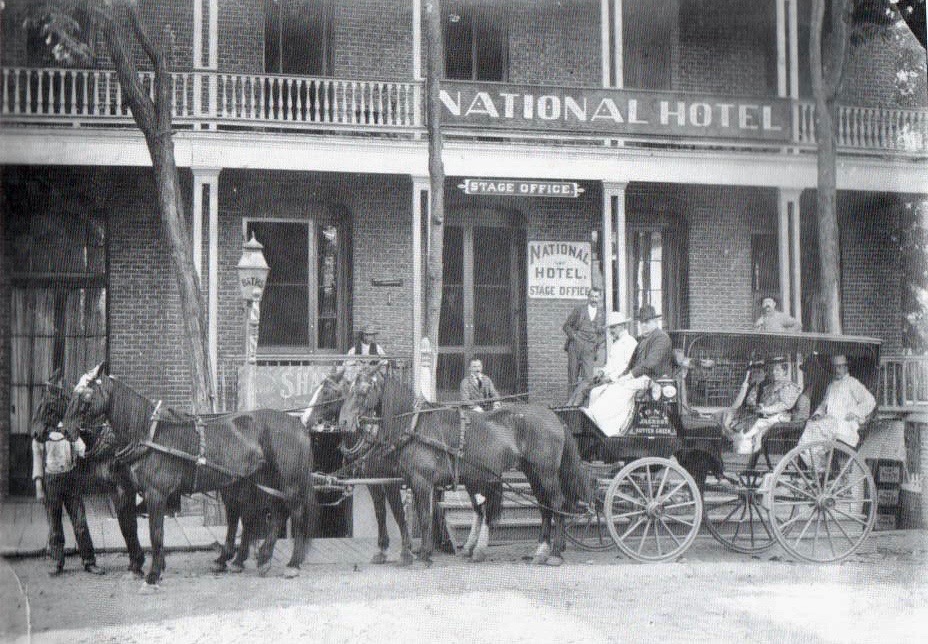

And Amador County had been on Lincoln’s mind, too. As the late historian Larry Cenotto discovered in his research, one of the final tasks the Great Emancipator performed before his slaying was authorizing a squad of Union cavalry to ride into the City of Ione, in Amador, to clear squatters from a new land grant. The arrival of those blue-clad soldiers would play an ironic role in the dead president getting revenge on The Amador Dispatch.

On April 29, 1865, The Dispatch published a lengthy column that, in the words of Cenotto, “celebrated Lincoln’s death and made it clear that the newspaper felt he’d gotten what he deserved.” The Ledger must have fired off a scathing response; but no amount of published words could sting Penry and Hall the way that destiny saw fit when their shocking statements reached the Union cavalry men who were still camped outside of Ione.

As the sun broke over Jackson’s main street on May 8, 1865, Penry and Hall were pulled out of their beds at gunpoint, arrested by Union forces and made to watch as the doors of The Amador Dispatch were chained shut. Fuming, the cavalry marched Penry and Hall on foot for 130 miles – all the way from Amador County to San Francisco – locking them up in the relatively new military prison, Alcatraz Island. Accounts from Penry and Hall confirm the two were literally shackled to balls and chains and fed crumbs and water.

Meanwhile, an angry mob looted and burned the office of The Amador Dispatch, leaving a smoldering pile of ash for all copperheads to remember.

“It’s a story that really tells us how the Civil War affected this remote state in the U.S,” Cenotto reflected a few years before his passing. “It tells us that in war, the authority takes away and restores liberties in its own good time. It tells us how one small county could be riven by political differences and animosities which, in time, were overcome if not forgotten.”

Six weeks after their arrest, Penry and Hall were released from Alcatraz on the humiliating condition of taking an oath of allegiance to the United States. Surprisingly, Penry spent the rest of his years in Amador County.

The Amador Dispatch and The Amador Ledger continued to experience a palpable tension for the next 125 years – until the McClatchy Company merged the two publications into one unified newspaper in the 1990s called The Amador Ledger Dispatch. Now owned by the Jackson band of Miwok Indians, the newspaper continues on under that banner to this very day.

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the host of the ‘Drinkers with Writing Problems’ podcast.

Be the first to comment on "Dueling pens, torch-wielding mobs and a march to Alcatraz: Looking back at the region’s most fiery newspaper war"