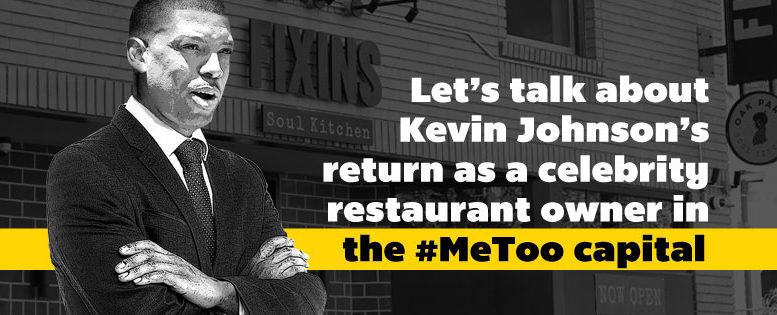

Sacramento didn’t author Kevin Johnson’s political downfall. Will the city support the accused molester’s makeover as a celebrity restaurant owner?

By Raheem F. Hosseini and Steph Rodriguez

Dear Sacramento,

Did you forgive or forget? Or did you never believe the girls at all?

It’s a late Friday morning inside Fixins Soul Kitchen, and Oak Park’s buzziest new restaurant is steady with early lunch traffic. Scan the crowd: Natty 20-somethings quaff pre-noon beers at the bar because they can; a tentative book club pokes in and settles on the patio; posses of friends and coworkers scarf down waffle stacks, brittle bacon, scrambled egg piles and deep-brined chicken slabs.

The 11 a.m. indicators are that Fixins is a hit—and a solid addition to the neighborhood’s fitful renaissance or sharp-elbowed gentrification, depending on whom you ask.

As for the man who owns this spot, this building, this block—his famous face hasn’t been this visible in a long while:

Kevin Johnson.

You remember K.J., Sacramento. He slunk out of office and out of the spotlight three years ago, amid resurgent allegations that he molested girls. You already knew these stories when you elected the former NBA great to be your mayor—twice. Johnson’s questionable behavior around young women became such an open secret that City Hall publicly reminded its elected officials to stop giving unsolicited hugs in 2013.

And yet Sacramento remained K.J.’s city, seemingly turning a blind eye to Johnson’s underage accusers so that it could bask in the shadow of its celebrity mayor. Until the national media told the rest of the country what you already knew, and a national audience recoiled.

But now he’s back.

For the first time since he dribbled out the clock on his political career, the retired professional athlete, one-time education reformer and ex-politician is fashioning his fourth reinvention—as the head of a budding restaurant empire. Johnson already has ownership stakes in three dining locations and says he plans to expand that portfolio beyond his native Oak Park.

Yet his latest chapter coincides with growing alarm about pervasive sexual harassment within the restaurant industry, where many workers are young, at the economic mercy of their bosses and lack formal workplace protections.

And you have a choice to make, Sacramento: Do you snap selfies and break bread with K.J. while his accusers hunger for atonement? Can you stomach another comeback?

The past is never far enough

Johnson was unavailable for comment, according to Fixins front-of-house manager Brian Rhee. But on the subject of sexual misconduct allegations, K.J. and his defenders have been steadfast in their denials—and Johnson has never been arrested, charged or convicted of a crime.

All that means very little to Mandi Koba.

Even 3,000 miles away and two decades after the fact, Johnson’s first known accuser can’t escape hearing what he’s up to these days.

Today, Koba is 40, pursuing a master’s degree in social work from George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., and juggling an internship at a free health clinic with being a mom of three. She has spent much of her adult life trying to be the advocate she wished she had in 1996, when she first told someone that Johnson was touching her inappropriately, including a night when he allegedly disrobed and fondled her inside his Phoenix guesthouse.

Koba’s decision to come forward sparked a police investigation and a controversial decision by the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office to forgo prosecution on the grounds that it probably wouldn’t win a conviction. It also upended Koba’s life in a city that said nothing of a 30-year-old man spending so much time in the company of a teenager.

“As an adult looking back, one of the things that’s most hurtful was that it was not a secret,” Koba said in a phone interview from her home. “Teachers, friends, friends’ parents, the adults that worked for Kevin, the Suns organization, his teammates saw me at events and nobody said, ’Hmm, this is weird. This isn’t right.’”

Instead, Koba felt that world turn on her, with kids at school taunting her and one of Johnson’s attorneys and a Phoenix radio personality going so far as to dismiss the girl as “a sick slut” in a story by the Phoenix New Times.

“You can’t get more public than being called ’a sick slut’ at the age of 17,” Koba said. “I mean, I was 17 and Phoenix was my whole world.”

Koba eventually had to find a new one, while Johnson returned to his old one. A decade passed. Koba thought she was doing well. Then came word that Johnson was running for mayor in Sacramento. The news capsized her recovery. Her story had been public even if her name officially wasn’t. And yet it didn’t seem to matter. K.J. was still his hometown’s hero. What did that make her?

“I had been really, really good until he decided to run for mayor,” Koba said. “To see people in Sacramento have this information and continue to go and vote and promote him and say, ’Yeah, this is the guy we want to represent us,’ was incredibly traumatic.”

It wasn’t just Koba that the electorate spurned. During the 2008 campaign, reports surfaced that a 17-year-old student at Sacramento High School, part of Johnson’s St. HOPE Academy, complained to a teacher that Johnson had groped her. The police investigated, but only after Johnson’s private attorney questioned the girl and she recanted.

Cosmo Garvin, a reporter at SN&R then, says local media tackled the story aggressively. As for how the public reacted, Garvin is blunt: “Nobody gave a shit.”

In November 2008, Johnson unseated Mayor Heather Fargo with 57% of the vote. Coverage of the sexual misconduct allegations evaporated, as if there was an unspoken decree that continued reporting would make it look like the Sacramento media had a vendetta against the city’s first African-American mayor.

Garvin would hear new allegations from time to time, but kept running into the same brick wall. “No one wanted to go on the record about anything ever,” he said.

Stymied on that front, Garvin shifted his focus to the way Johnson blurred the lines between his political responsibilities and private ambitions. Garvin investigated Johnson’s controversial use of solicited donations called “behests,” his multiple failed attempts to consolidate power under a “strong mayor” form of governance, the numerous Johnson initiatives that fell short of their promises and how the mayor used city staff in a hostile takeover of a national black mayors association.

But where the local media establishment softened on Mayor Johnson, a New York-based sports news website came in hard.

Deadspin to rights

Deadspin reporter Dave McKenna had heard unsettling rumors about K.J., but didn’t decide to look into them until 2014. That was when Johnson was receiving national accolades for representing NBA players who were threatening to sit out if Donald Sterling was allowed to remain owner of the L.A. Clippers following leaked racist statements. McKenna did a cursory Google search and says he was surprised by how much was already on the record, particularly the Phoenix case involving Koba.

“I was amazed … that he had attained any kind of position just based on what was out there,” McKenna told SN&R. “I found him not only unelectable, but unemployable. I didn’t get how somebody with this track record would be able to show his face in public.”

McKenna’s reporting picked up where the Phoenix New Times left off, obtaining video of a police detective’s interview with Koba, who comes off credible and careful not to overstate or exaggerate her accusations against Johnson. At one point, she tells the detective she doesn’t want to ruin Johnson’s life or have him spend “100 nights in jail or anything.” She just wants Johnson to leave her alone and not do it to anyone else.

Koba went public as Johnson’s teenage accuser in Deadspin’s 2015 coverage. She says that was the first time she watched the video or read the police report. She found herself wanting to help that too-thin girl folded into the corner of a windowless interrogation room. She didn’t understand why so many others did the opposite.

Media scrutiny finally reached a tipping point for Johnson in March 2016, which was ironically supposed to be a really good month for him.

ESPN’s acclaimed documentary series 30 for 30 had produced an entire episode devoted to the narrative that Johnson saved the Sacramento Kings from leaving town. But then another cable sports series, HBO’s Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel, scotched that story with its own K.J.-centered piece—a damning exposé that included interviews with several Johnson accusers, including former St. HOPE students and a mother who accused Johnson of having an inappropriate relationship with her daughter.

ESPN shelved its 30 for 30 profile, forcing Johnson to announce there would be no screening of the episode on stage at his Guild Theater.

And yet some in Sacramento still had a hard time letting go of their mayor. McKenna recalled the next day’s column from longtime Sacramento Bee columnist Marcos Breton.

“The headline was, ’No smoking gun,’” McKenna recalled. “I’m like, ’That’s what you get out of this?’ I mean, it was like different people from different decades, different cities, describing the same evilness and you’re just going to discount this? And that seemed right in line with the coverage he always got in Sacramento.”

Ironically, Johnson is now resurfacing as Deadspin is imploding. As McKenna spoke to SN&R, news was breaking that the entire editorial staff had walked out on new management in protest of a mandate to drop all non-sports coverage.

Which means that the news outlet perhaps most responsible for causing Johnson’s political downfall is crumbling just as the former mayor is rising.

As for Koba, she says her experiences have left her cynical. She’s no longer surprised when Johnson makes high-profile public appearances—meeting with President-elect Donald Trump in November 2016, representing the city’s Major League Soccer hopes the following year in New York, hosting the Rev. Al Sharpton at his Guild Theater earlier this year to discuss the Stephon Clark case or taking selfies in front of his new restaurant with prominent locals, including local NAACP chapter president Betty Williams, a candidate for City Council.

Koba says she’s not surprised because she doesn’t think many in Sacramento ever believed her in the first place.

“No. 1, I’ve never felt that Sacramento felt like any of the—as you guys call them—’allegations’ were credible,” Koba said. “For me, I would hope that if somebody viewed them as credible … they wouldn’t want somebody who preyed on young girls to be their leader.”

Confronting crass kitchen culture

During a chilly February morning inside the Milagro Centre on Fair Oaks Boulevard, 75 people noshed on breakfast sandwiches and fresh fruit as three female chefs sat on a stage and discussed sexism and sexual harassment within the restaurant industry.

As part of Valley Vision’s “Women on the Line” talk, N’Gina Guyton, who owns South, a Southern-style comfort food joint in Southside Park, revealed that she was 17 when a coworker pulled her into a walk-in freezer and assaulted her. She wants to make sure nothing like that happens under her watch. She says her employees’ well-being is her top priority, especially in an industry that still feels like a boys’ club.

“Being in a very male-dominated industry, it’s very important to tell the story of what it’s like to be a black female in this industry and what we go through,” Guyton told SN&R. “Every day customers see me, they’re going to see a smile, they’re going to see me being outgoing. But I don’t want people to have assumptions that there haven’t been hardships, or that there hasn’t been racism or sexism getting there.”

Bad behavior is widespread in the restaurant industry, according to multiple studies.

In October 2014, the Restaurant Opportunities Centers United and Forward Together released the results of a survey of 688 past and present restaurant workers in 39 states. Their report found that 60% of female workers said that sexual harassment was a regular part of work life and 50% reported “scary” or unwanted sexual behavior.

The survey said the harassment is made worse by employees’ reliance on tips to make ends meet and is twice as common in states that have a lower minimum wage for tipped workers.

In 2017, Buzzfeed compiled 20 years of federal complaints to show that restaurant employees filed more sexual harassment claims than workers from any other industry. Again, economically vulnerable workers were more likely to face harassment.

That isn’t news to Jessica Stender, senior counsel for workplace justice and public policy at Equal Rights Advocates, based in San Francisco.

While California doesn’t have a lower minimum wage for tipped workers, employees still rely on gratuities and worry about losing hours. “Especially if you’re a low-wage worker, you really don’t have a safety net,” Stender said.

Her group is one of 50 nonprofits in the Stronger California Advocates Network, which seeks firmer workplace protections. In the past two years, the network has helped push through new laws that extend the filing deadline for harassment claims from one to three years and ban “no rehire” clauses in settlements, which Stender called “inherently retaliatory.”

State Sen. Holly Mitchell helped carry Senate Bill 778, which requires even small employers to offer sexual harassment training and makes training resources available from the state.

“It’s clear that a culture shift needs to happen in the workplace,” the Los Angeles Democrat said.

But not every problem has a legislative solution, Mitchell cautions.

“I have a permanent refrain, and it’s that I cannot legislate morality,” she said. “To me, the harassment that occurs is a symptom of a deeper issue—and that’s a power imbalance and inequity in our workplaces.”

Guyton, who opened South in 2014, is doing her part. She’s getting ready to launch the Verity Project, a mental wellness initiative that she hopes will be available for local restaurant workers by the end of the year. It will help subsidize the cost of two different treatment options—a 10-week group therapy program for men, women and LGBTQ workers at $10 a class; and individual therapy sessions covered up to 60% depending on income.

Guyton’s advice to both women and men who experience harassment is to speak up, keep a journal and confide in someone they trust. Speaking up can help, even if the accused isn’t held legally accountable.

“People talk about ’cancel culture,’ especially after R. Kelly: ’We’re not listening to his music,’ ’We’re not buying his albums,’” Guyton said.

The same could apply to K.J., whose growing restaurant empire concerns Guyton.

“I can’t speak for the entirety of the black community,” she said. “I can’t speak for the entirety of the restaurant community. I can only speak of my own experiences that I have had, and I am not one that ever forgets. So for me, I just don’t get it.”

Inside the K.J. triangle

Since celebrating its grand opening in late August, Fixins has boasted a full house most afternoons and evenings. For Oak Park resident Lavinia Phillips, that doesn’t sit right.

“I went once,” Phillips said. “Kevin was in the back in his little hiding spot. It’s almost as if he’s purchased an area where everyone kind of respects him because he’s ’the man.’ He’s really not. He’s just a person with money that can buy himself into safety.”

Yet at a bustling Wednesday lunch rush last week, diners appeared content. The underlying truth is that residents in Oak Park, or elsewhere, will ultimately decide where they are going to spend their time and their money. New, hip restaurants that offer jobs and revitalize buildings have potential and Fixins’ website says it’s hiring for all positions.

But after her visit, Phillips said she won’t be back. “Absolutely we should not forget. But, to be honest, there isn’t anything that we can do about it, because in reality, he wasn’t convicted of anything,” she said.

There is no denying that K.J. has put his money where his roots are. And throughout the years, Johnson has acquired a lot of Oak Park real estate.

On the corner of 35th Street and Broadway is K.J.’s retail compound—the 40 Acres Art and Cultural Center, a handsome, brick-and-mural complex that includes the Guild Theater, Underground Books (run by Johnson’s mother Georgia West), the Old Soul coffeehouse and Twelve Loft Apartments. Fixins, Johnson’s second entry into the local foodie scene, stands just around the corner from Underground Books and down the street from the revamped Oak Park Brewing Co., another K.J. joint with an intriguing back story.

Oak Park Brewing reopened under new management in June, nearly a year after it was forced to close due to several pest-related health code violations.

Chris Jarosz, co-owner of Broderick Roadhouse and one of Oak Park Brewing’s main investors, approached Geoff and Rebecca Scott, who helped start Track 7 Brewing Co., to brew beer and run marketing and design, respectively.

The Scotts left Track 7 amid complaints that CEO Ryan Graham made inappropriate sexual remarks toward female workers. In February, the Scotts filed a wrongful termination lawsuit against Graham, his wife Jeanna and their former investors.

Geoff Scott said he and his wife are sensitive to claims of sexual misconduct and did have concerns about trading one scrutinized partner for an even more scrutinized one.

“It definitely was a concern of ours, and we treaded very lightly on it,” Scott said. “We consulted our attorney. Basically, our attorney says we will still support what we believe in, and if anything happens at Oak Park Brewing Co., we’re still going to speak our mind about it—no matter who it is.”

In the meantime, K.J.’s empire expands.

SN&R traced 39 properties to Johnson and his holding companies, triple the number he reported when he left the mayor’s office in December 2016. He is also a member of at least three restaurant-related limited liability corporations, including Broadway Triangle LLC, which owns the land beneath the closed Oakhaus, which is rumored to reopen as a pizza-and-beer joint.

A shuttered Oakhaus now shows signs that indicate K.J.’s third restaurant is coming this fall.

Oak Park Brewing Co. reopened this summer with help from K.J.’s investment. (Photos by Steph Rodriguez)

Johnson’s growing restaurant portfolio exists within the confines of his Oak Park home court, making the neighborhood a favorable petri dish to test out his latest ambitions. One thing’s for sure: Johnson will have one of his staunchest lieutenants helping him.

According to California Secretary of State business filings, the listed agent of service for process for Fixins Sacramento LLC is Kevin J. Hiestand, K.J.’s longtime lawyer and business partner. Hiestand also holds that designation for three St. HOPE corporate entities and Kynship Development Company, a subsidiary of the Kevin Johnson Corp., and has run interference for his influential client ever since K.J.’s Phoenix playing days, even questioning Johnson’s underage accuser at St. HOPE before the police were contacted to investigate, according to reporting by the Bee.

“The same fixers he had in Sacramento with the sexual assault allegations were the same fixers he had with Mandi in Phoenix,” Deadspin’s McKenna said. “They travel. They travel and fix the same kind of situations.”

The people around Johnson concern Koba, maybe even more than does the idea of Johnson occupying a position of power and influence in an industry with a young, mostly female staff.

“What Kevin did, he’s one person,” she said. “But I think an even bigger issue are the people who enable him and protect him. … Because it could’ve stopped with me. And I don’t think I was the first one, but it could’ve stopped with me.”

But it’s also not just about K.J. and his helpers or hangers-on, Koba adds. It’s about you. It is, and always has been, about Sacramento.

“I just want people to know that their voice matters,” she said. “Their choices matter, and complacency is dangerous. You all voted him in. You all affirmatively chose him to be your leader for a very long time. And now you could choose something else.”

If you’ve been the victim of rape or sexual assault, you can contact the Rape Abuse and Incest National Network crisis line at (800) 656-HOPE or CALCASA Rape Prevention Resource Center at(916) 446-2520.

Be the first to comment on "The problem with K.J.’s comeback"