After backstage drama, Elk Grove teens force a reckoning with the theater teacher they say mistreated them and the school that didn’t stop her

Elijah Muller, a teenage actor playing a fool-actor, said his lines and stepped backstage.

It was premiere night, fall 2018, the first show of the new school year. Laguna Creek High presents A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare’s comic farce about mortal love and faerie magic and a play within a play. How fitting:

This is the story about the ugly drama hiding within a prestigious high school setting.

Elijah ducked behind a block of stadium seats, exited the school’s Black Box Theatre and hustled through the cluttered workshop toward the classroom that doubles as the drama club’s green room. It’s already been a bad day, a bad month, a bad couple of years for the students in the school’s theater program. That night the tensions boiled over. That night the curtain lifted on a teacher the kids call Ms. G.

Elijah remembered hearing the crying before he saw it. Then he opened the door.

“There are crying students everywhere. There are students on time out in dressing rooms. There are students outside. But the common theme is they’re all distressed. They’re all sobbing,” Elijah recounted. “This was pure and unchecked wrath.”

Elijah said that’s when he saw his teacher get in the face of a male student. He said he stepped between them, the teacher retreated to her office and shut the door.

You won’t hear from the teacher in this story. SN&R made multiple attempts to reach Sarah Goodenough, including a visit to her home on Saturday. Emails, phone calls and text messages all went unanswered. Laguna Creek High and Elk Grove Unified School District officials also declined to be interviewed.

But the students and their parents provided the same composite sketch of a teacher they say preyed on her students’ vulnerabilities in mostly subtle ways—until the night of Oct. 27, 2018. SN&R interviewed four students and one parent who were present that night and gave similar accounts.

“The rest of the show was damage control,” remembered Trinidad Reyes, who played the part of Oberon.

“I just wanted to be like, ‘I’m sorry, we can’t carry on,’” added drama club president Madeline Pogue, who starred as Puck. “No one knew about what was happening.”

But before the night was over, the drama club students and their parents documented what Ms. G allegedly said and did to them.

Before the school year is over, the students’ refusal to stay quiet forced a high school with a carefully crafted image to confront troubling allegations of teacher abuse and administrative neglect.

Before this story is over, you will understand that tyrants can reign on the smallest of stages—but not without a little help.

Act I: Vulnerable students, sensitive information

Except for half a week in April, Goodenough hasn’t shown up to work in nearly six months, parents and students say. But there are some things we know about her.

According to the public employee database Transparent California, Goodenough, who is listed under her former married name Sarah Woodward, first started teaching in 2013 as a part-time middle school teacher in the Lodi Unified School District and a substitute for the Elk Grove Unified School District. Goodenough went full time with Sacramento County’s largest school district in 2015, first teaching language arts to seventh and eighth graders. Goodenough joined Laguna Creek High the following year in the Visual and Performing Arts Department and took over as adviser of the LCHS Theatre Company.

As of 2017, Goodenough was the lowest paid of the five theater department teachers working for the district, Transparent California data shows.

Laguna Creek’s theater program isn’t so much a crown jewel as an afterthought at a school with an award-winning color guard and the district’s only International Baccalaureate program, students and parents said.

Most drama club members will never step foot on a Broadway stage. Instead the program, which includes elective theater classes and the theatre company, tends to attract misfit kids with rough home lives or tumultuous inner ones, as well as students who simply don’t want to go home after last bell.

“Theater classes are predominantly for non-honors kids, kids who probably don’t want to be there, ‘cause it’s like one of the classes they kinda just put kids into,” explained Elijah, 18, a senior who took theater his first three years and is currently a club officer. “So it’s hard to manage.”

Initially, some club members said they believed the energetic Goodenough, who was still Ms. Woodward then, was an ideal pick to manage it.

“When Ms. Woodward came in, she buckled up her bootstraps and she was ready to go,” Elijah said. “It was kind of a breath of fresh air at first, like, ‘OK, this is an adult who knows what they’re talking about and they’re gonna get stuff done.’”

“We were all like in awe of her,” added Lauren Sproul, 16, who joined the club as a freshman, the same year as her teacher.

That positive feeling soon faded.

SN&R interviewed five current students and one former one who took both theater classes and were members of the drama club while Goodenough ran the program. They all said she quickly made them uncomfortable by plying them for personal information through mandatory assignments and graded theater “games.” And when some students declined to share those details, they said Goodenough tried to get personal details in other ways.

“It never felt like it was up to us to open up to her,” said Laguna Creek High graduate Jacqueline Laybourn, 19. “It felt like she was digging it out of us. Privately, alone, trying to dig it out.”

Jacqueline said she made the mistake of sharing something about her then-rocky relationship with her parents during an interclub activity. While what students said during the activity was supposed to stay in the classroom, Jacqueline said Goodenough pulled her into her office after it was over and tried to find out more. After Jacqueline demurred, Madeline said Goodenough started asking her about her friend’s home life.

“She asked me a couple of times. She asked me about her relationship with her parents,” Madeline said. “In doing so, she then told me what she knew.”

That was common, the students said. Goodenough routinely shared what students privately revealed during other classes, the students and two parents said. Students said they learned which classmates said they were abused at home, who had learning challenges, who might be in the closet or virgins, even who struggled with depression or self-harm.

Parents heard this gossip, too.

“I know things about them that I shouldn’t know,” said Gin Brewer, whose daughter takes theater and belongs to the drama club. “She uses information about them in not-good ways.”

Amy Pogue, Madeline’s mother and a drama club volunteer, said it wasn’t unusual for Goodenough to vent to her about which students she hated. Pogue and several students said Jacqueline was the frequent object of her teacher’s loose talk.

“She would outwardly tell people that she didn’t like Jacqueline and that she was a terrible person,” said Maya Brewer, Gin Brewer’s daughter.

The teacher’s focus would soon shift onto Maya, the students said, with Ms. G using the 16-year-old junior’s most sensitive information as leverage—and then going farther.

Act II: A ‘thorough investigation’

Laguna Creek High and Elk Grove Unified released separate statements about their commitment to student safety.

In his email, Laguna Creek High principal Doug Craig wrote that the students’ allegations “called into question our expectations regarding professional conduct and ethical behavior,” and prompted a “thorough investigation” that resulted in at least one change: The school will have a new theater teacher and director starting next year.

But Goodenough remains employed by the school, Craig confirmed. While her 2019-20 assignment is yet to be determined, the students and their parents worry that all their months of whistleblowing will accomplish is getting Ms. G a promotion of sorts, by moving her out of an elective and into a mandatory class such as English.

“What worries me—and this you can print—is she’s going to be put in another classroom with another group of kids. That does worry me,” Pogue said. “While I can feel somewhat for a person like that, that person should not be around children.”

Pogue and her daughter presented the principal’s office with a series of written statements that alleged verbal abuse by Goodenough and two non-fingerprinted adults she left students alone with during the Oct. 27, 2018 performance of Midsummer. That started the administration’s “thorough investigation,” but it didn’t include interviews with any of the students who provided those declarations.

SN&R reviewed copies of the statements, which include accounts that Goodenough told one student she was “too fat” to act.

“I mean, some of the things she said to these students,” said Pogue, who was at the performance selling tickets. “She came down on the kids like a bag of hammers.”

“She used everything in her arsenal,” Brewer added.

Parents also said the school district failed to fully investigate what happened.

“No one from the district office ever spoke to them,” Brewer said of the students. “No one from the district office ever spoke to us. And all our attempts to tell them [what happened] have been met with, ‘Well, this is what we think is best for them.’ They do not care.”

In its statement, the district said it does.

“The District takes all complaints regarding student safety seriously,” Elk Grove Unified communications director Xanthi Pinkerton wrote in an email. “While the District cannot comment on confidential personnel matters, the District can confirm that all complaints regarding teacher misconduct are thoroughly investigated, and during an investigation of an allegation related to campus safety, the District’s practice is to remove the teacher from the classroom during the pendency of the investigation. Teachers who are deemed to pose threats to student safety are not returned to the classroom.”

The students and parents said that if the district actually listened to them, Goodenough might not be allowed to teach again.

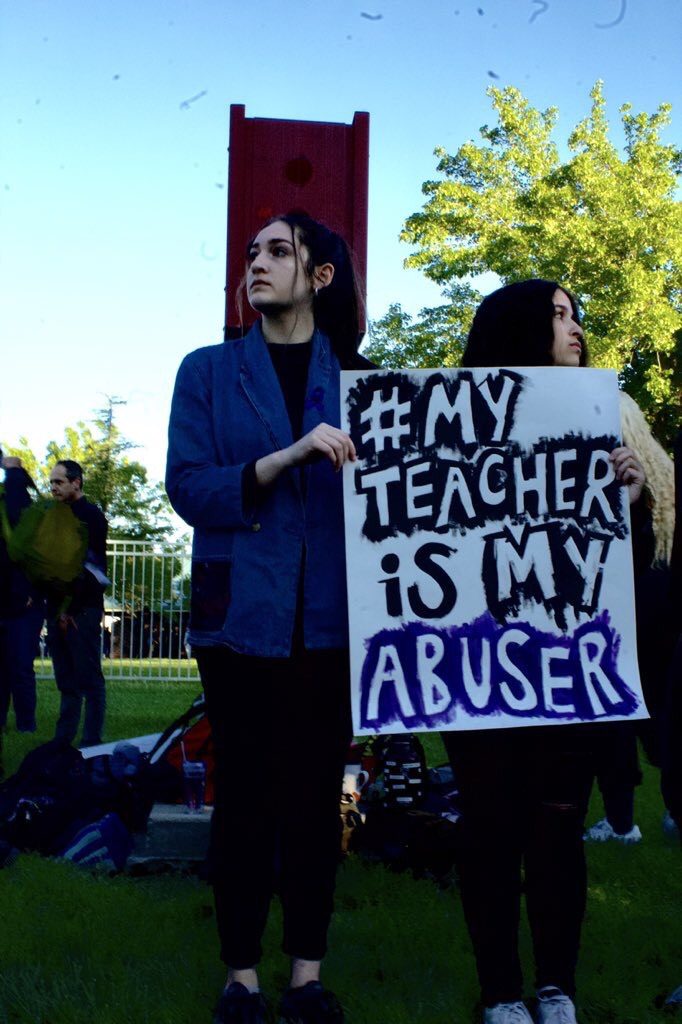

Laguna Creek High senior Madeline Pogue, 18, said she never quite warmed to her drama teacher because of her experience working with other theater companies. “You can use trauma and things that happened to you to get to a better performance. I’ve seen it done with casts a lot of times. But it is never handled so publicly.” (Photo by Bella-Mia Bates)

LCHS Theatre Company student officers donned jean jackets embossed with names gotten from the Wu-Tang Clan online name generator.

Act III: ‘And then she slapped me’

Maya would have told officials some alarming things that they don’t know.

In the summer of 2015, Maya and her mom moved to the area from Southern California. This was after Maya finished the eighth grade, a tumultuous year during which Maya experienced severe depression and was hospitalized following a suicide attempt, she and her mom shared with SN&R. That information was never supposed to be public, but then Goodenough got a hold of it.

Freshman year in a new city at a new school wasn’t shaping up to be an easy one. Brewer said she felt like her daughter needed an extracurricular activity that would foster social interaction and cameraderie with her peers. They consulted Maya’s therapist, Brewer recalled.

“That’s when I said, ‘Fuck it, you’re going into the theater program,’” Brewer said.

She half-regrets that decision now. “The kids in that program were amazing,” said Brewer, who is herself a teacher in the district. “The teacher in that program was derelict in her duties.”

Maya enrolled in theater the second half of her freshman year and joined the drama club at the start of sophomore year. Maya said she essentially became Ms. G’s personal assistant, told to take jobs away from drama students that Goodenough clashed with—like Jacqueline and Lauren—and becoming the keeper of her teacher’s classroom keys when Ms. G left early.

“The first time her keys were in my house, I was blown away,” Brewer said.

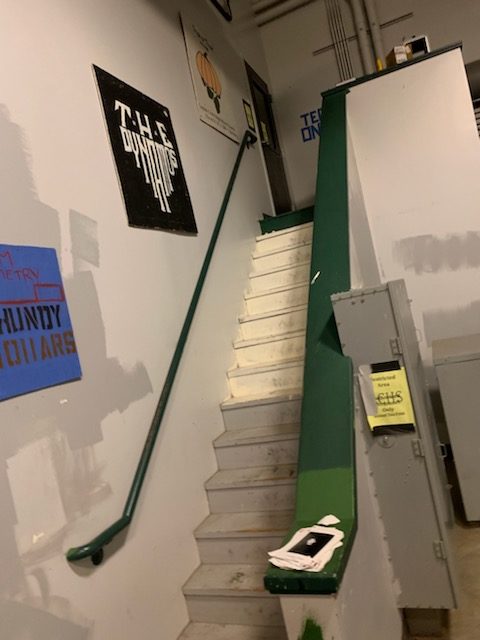

Maya wanted to quit the drama club. In February 2018, she sat up in the Black Box Theatre’s technical booth writing a letter to her fellow club members explaining her decision. She remembers being called down to help with something and said Ms. G passed her on the narrow stairway leading up to the booth. A little while later, Ms. G summoned Maya to her office and showed her a photo she took with her cellphone. It was of the letter.

Maya said Goodenough told her that as a mandated reporter, she was required to report any threats of suicide or self-harm to the authorities. The letter didn’t contain any such threats, but Maya said Ms. G had already revealed to her that she had read her personal file and knew about her struggles during eighth grade.

She then sent Maya to go sit in the theater with the other kids. That’s when Maya said she learned her teacher had already told the other students about her “suicide” letter.

Maya hadn’t told her classmates about that part of her life because she didn’t identify with those feelings anymore or want to be identified by them. But her teacher had now put her private life onto a high school stage.

“Everyone sat around pretending nothing was happening,” Maya said. “Until a bunch of cops showed up.”

The stairway to the tech booth where Maya penned her “suicide” note.

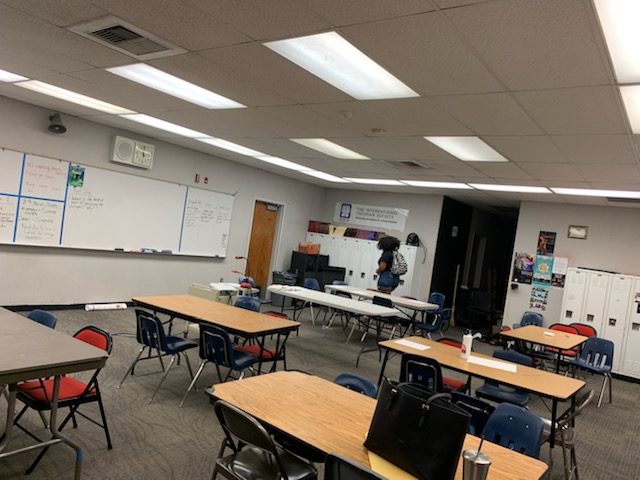

The classroom/green room of the theater department.

Goodenough’s office where Maya and her mom were interviewed by police. (Photos by Gin Brewer)

Two officers asked Maya to follow them into Goodenough’s office and made small talk until Maya’s mother arrived about 10 minutes later. Ms. G left the office, but mother and daughter said they still felt on display. The office is small with two windows looking out into the classroom, and its door wouldn’t close all the way with four people crammed inside. Ms. G and the remaining students sat in the classroom watching.

“She did nothing to hide the spectacle of this from any other human,” Brewer said. Brewer said one of the officers used his body to try to block the view, “becoming my second-favorite person that day.”

Her first favorite, the one who worked so hard to get better, fielded uncomfortable questions, telling officers that, yes, she once tried to take her life but, no, didn’t think about hurting herself anymore. The officers read the letter that Goodenough had reported. It wasn’t a cry for help. It was a resignation letter from the drama club.

“I 100% felt like it was done to discredit my daughter,” Brewer said. “I never felt like it was done out of any concern.”

Maya returned to drama club the next day pretending like nothing had happened. But she said she had gotten the message: Her secrets weren’t hers.

Maya started accepting more tasks from Ms. G. She cleaned the theater and locked up. She even babysat for her teacher. One time when she was left unattended in the theater, a boy at the school allegedly forced himself on her and kissed her. That incident resulted in reports to the school and police.

Ms. G told her classes they could no longer use the Black Box without adult supervision because Maya claimed she had been sexually assaulted, several students said.

By this time, Maya said it had become an almost daily occurrence for her teacher to “just scream in my face.” When Maya babysat, she said Goodenough often railed about drama club, left the house and returned in a fouler mood. Maya said her teacher knocked the clutter off her tables and sometimes threw things. Sometimes they hit her.

One night in March 2018, Maya said, Goodenough was yelling especially loud. Her partner sequestered herself in the bedroom. Her son woke up and called for his mother. Maya said when she told her teacher she had woken up her son, she struck her.

“And then she slapped me,” Maya said.

She said her teacher’s partner drove her home that night. They didn’t talk. The babysitting offers petered out. When they did come, Maya said she made excuses. She didn’t tell anyone what happened, not even her mom. Not until the Midsummer nightmare.

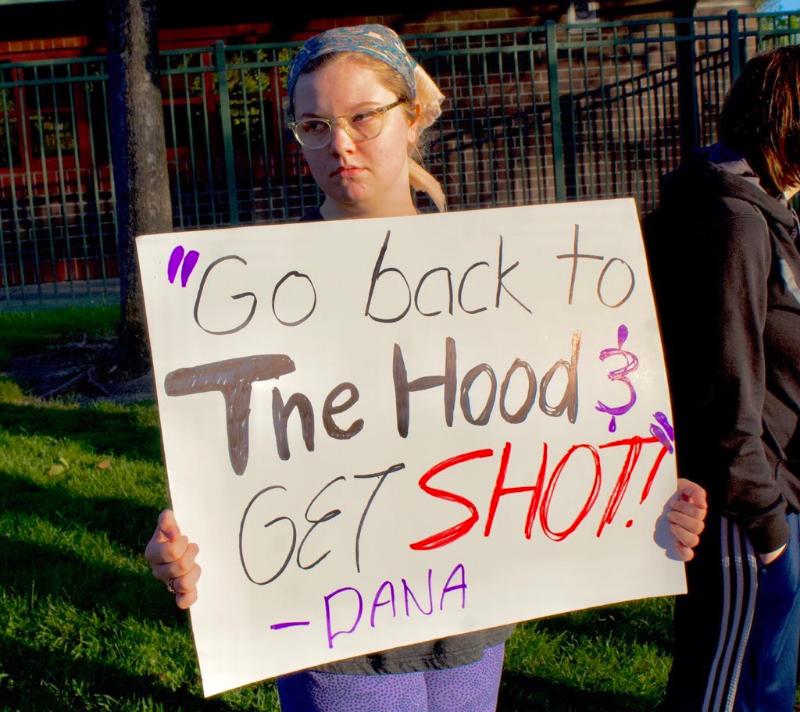

Students held signs of things their teacher or her adult assistants reportedly said to them during an October 2018 performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. (Photo by Justin Pogue)

Several students said teacher Sarah Goodenough’s girlfriend snapped at an African-American drama student to “go back to the hood and get shot” during the October 2018 performance. (Photo by Bella-Mia Bates)

Act IV: A statewide blind spot

At least two other teachers accused of troubling behavior are still on Laguna Creek High’s payroll, including a special education teacher who’s currently being sued for allegedly punching a developmentally disabled student in September 2016, and a track coach who reportedly threatened two black football players who knelt before a game that same year.

The special-ed teacher’s attorney doesn’t deny the specific allegation. Instead, in his answer to the claim, the attorney writes that his client acted “lawfully and with the degree of force necessary to prevent injury to him/herself and to others whom he/she was charged to protect and supervise.”

According to court documents, the plaintiff has failed to appear for two of the last four court hearings, incurring a $150 fine on April 4.

In California, information on teacher departures and firings is difficult to find.

Despite requiring schools to report reams of micro-specific data concerning student performance and demographics, the California Department of Education doesn’t ask some pretty basic questions about the educators, administrators and support staff who are paid to help them succeed.

That makes individual school districts the lockbox of this information. Like law enforcement agencies, districts are reluctant to disclose even basic figures about personnel suspensions and dismissals. Unlike law enforcement agencies, there isn’t a new law forcing them to provide information about substantiated misconduct. (Elk Grove Unified did not provide requested data on teacher suspensions and firings as of print deadline.)

What California does have when it comes to investigating and responding to teacher misconduct is the state Commission on Teacher Credentialing, which is the busiest it has been in at least four years.

The biggest reason is that there are just more people applying for teaching credentials, more than 2,800 applicants a month in the 2017-18 fiscal year.

At the same time, school districts and members of the public are leveling more complaints against teachers and other public school employees. The annual report of the commission’s Division of Professional Practices, released in September, attributed the sharp rise to “some highly publicized cases of misconduct” starting in February 2012, and also to its own user-friendly website.

In 2017-18, the division investigated the most complaints in four years regarding serious crimes or felonies (942), sex crimes against children (331) and adult sexual situations (110).

Elk Grove Unified has experienced a raft of these alleged crimes, with eight employees arrested on suspicion of sexual battery and other inappropriate conduct involving minors. Laguna Creek High was among the latest schools in the district to join this worrying trend. In January, Elk Grove police arrested Lucas Donovan Melville, a 24-year-old marching band volunteer, for statutory rape of a student.

On April 9, Melville was sent to jail following a court appearance. He faces 28 felony counts for statutory rape and other sex crimes involving a minor.

The teaching commission’s enforcement division had 5,895 open cases in 2017-18, 65% related to alcohol use or crimes, and said that number has steadily risen “based largely on an increase from applicants with a criminal history.”

The commission took disciplinary action in 894 cases in 2017-18, also the most in four years.

Neither Goodenough nor the accused special-ed teacher have any adverse actions on their records from the commission.

One thing’s for sure: California is hiring more teachers.

Nearly 21,000 teachers were hired during the 2018-19 school year, compared to 13,000 in 2012-13, according to a report from the Commission on Teacher Credentialing. Sacramento County estimated 807 new hires this year, and Elk Grove Unified 243, including 27 in the English/Drama category, state education data shows.

Depending on how the rest of this story unfolds, the district could be seeking one more next year.

Act V: All quiet on the district front

The Midsummer Night‘s show took place on a Saturday evening. The following Monday, Madeline and her mom delivered the student declarations to the principal’s office.

Goodenough didn’t show up to work that day. She stayed gone for five months. Then, on April 1, Craig sent out a brief email informing parents and guardians that Goodenough was returning from leave that Wednesday as a theater teacher, “but will no longer be the Drama Club Advisor.”

Maya’s father texted her mother: “Was it an April Fool’s joke?”

It wasn’t.

Maya remembers having a panic attack, then just shutting down when she learned Ms. G was coming back. “That was my biggest fear, having to see her again,” Maya said.

Her mom tried to pull Maya from the class, but Brewer said the district told her the only way to do that was to withdraw her daughter from school entirely, setting her back at least a half-year.

“Effectively your solution is to punish the victim,” Brewer said. “You’ve not only put them back in the room with an abuser, you’ve put them in a room with an abuser who has power over them.”

Amy Pogue, Madeline’s mother, said it can be hard for adults to remember that feeling of being trapped in a classroom.

“That’s an incredibly unfair place to put them in, especially when they were brave enough in the first place to come forward,” she said.

On April 3, Theater 3 was Maya’s final period of the day. Several drama club members entered the classroom together. Maya snagged a seat at an angle so her back was turned to Ms. G and refused to look at her for the entirety of the 90-minute class.

“She was mostly acting happy and bubbly,” Maya said. “She was acting like she used to.”

Ms. G taught for only three days. By the following Monday she was MIA again. She hasn’t been back to class since April 8. But the students, especially the seniors who are graduating next month and students with younger siblings about to start high school, want a clear finale. They don’t want Ms. G back.

Students protested outside the school for three mornings the following week, holding signs with some of the things they say their teacher said to them. Dozens of students, not all of them involved in the theater program, joined in. Madeline said a teacher stood with them on the last day.

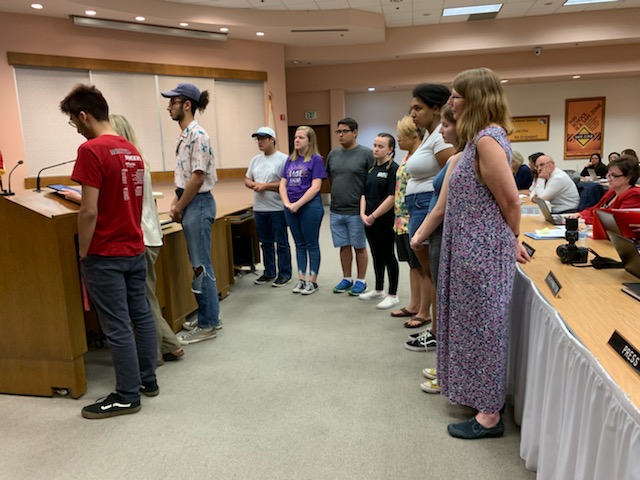

On April 23, Madeline addressed the Elk Grove Unified school board with 10 of her classmates standing behind her.

“I’d like this to get handled before I’m gone,” she told school board trustees. “If you recall in loca parentis, you know, we are supposed to trust the people there as if they’re our own parents. And we ask that we can trust you again. We’re scared. We are asking for help, and we are asking that she no longer has the power to abuse that many children ever again.”

Madeline and the other students said they haven’t received a response from the board. They said they’re pessimistic the district will listen to them. They’re starting to sound like the adults.

As for Maya, she’ll be back for senior year in the fall. Like all the other students SN&R interviewed, she had a mostly positive view of Laguna Creek High. She likes most of her teachers. She and the other theater kids raved about “Mr. Z,” the substitute who took over drama club from Ms. G. Maya said she’d only take drama again if he was the club’s advisor.

“The majority of it is good,” she said of her high school experience. “It’s just that the parts of it that are bad are really bad.”

As a drama teacher who took over from a “bad drama” teacher, I have seen how much damage bad teachers, especially those of us who deal directly with some of the most PERSONAL and intimate issues with students. Even though I have now been there for 2 years, I am still dealing with mental fall out from that Bad teacher. First – WELL DONE STUDENTS for SPEAKING UP!!! THIS BEHAVIOR IS UNACCEPTABLE to ANY respectable teacher in our profession. Second, for over 40 years, the state of CA has been without a Theatre credential or ANY training for theatre teachers accepted by the state. I am happy to say that as of 2016, the CA law has now adopted Standards which went into affect this past January and we will soon have programs which will train the next generation of theatre teachers who we know will have to deal with intimate issues. FINALLY – I am grateful for my admin who took actions against the teacher who preceded and listened to the students and parents and took immediate action. For this admin and school board to let this go on for as long as it did, is not only unacceptable, but is also an outrage and disservice to the students in the program. Too often our drama departments are ignored or referred to as dumping grounds to put ANY student in. I hope that WHEN that ADMIN and SCHOOL BOARD are held accountable, they actually learn something about those theatre programs in their district and learn the difficulties that need to be addressed as the school moves forward, including how drama instructors often have to apply psychology into the classroom in a way that let’s students learn and not used in ways that are used against students.