Still fighting for the right to vote

Our voting rights did not come easy. I’m reminded of that often during Black History Month and this centennial celebration of the 19th Amendment that enabled American women to vote in 1920.

Originally, only property-owning white men could vote. No one else was granted full citizenship or allowed to participate.

Frederick Douglass, one of our nation’s leading abolitionists, risked his own freedom as a gifted journalist, orator and writer. And he was an ardent advocate for women’s rights. As the only African American man at the Women’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls in 1848, he spoke in support of women’s rights, and for women to speak for themselves.

“I believe no man, however gifted with thought and speech, can voice the wrongs and present the demands of women with the skill and effect, with the power and authority of woman herself,” Douglass said.

Three years after the Civil War ended, the 14th Amendment formally granted African Americans citizenship in 1868. But it took the 15th Amendment in 1870 (after continued pressure on Congress) to overtly grant voting rights to African American men.

That amendment enabled African American men to vote — and even to run for office — at least for a time. During the 1880s, about 2,000 African American men were elected to public office.

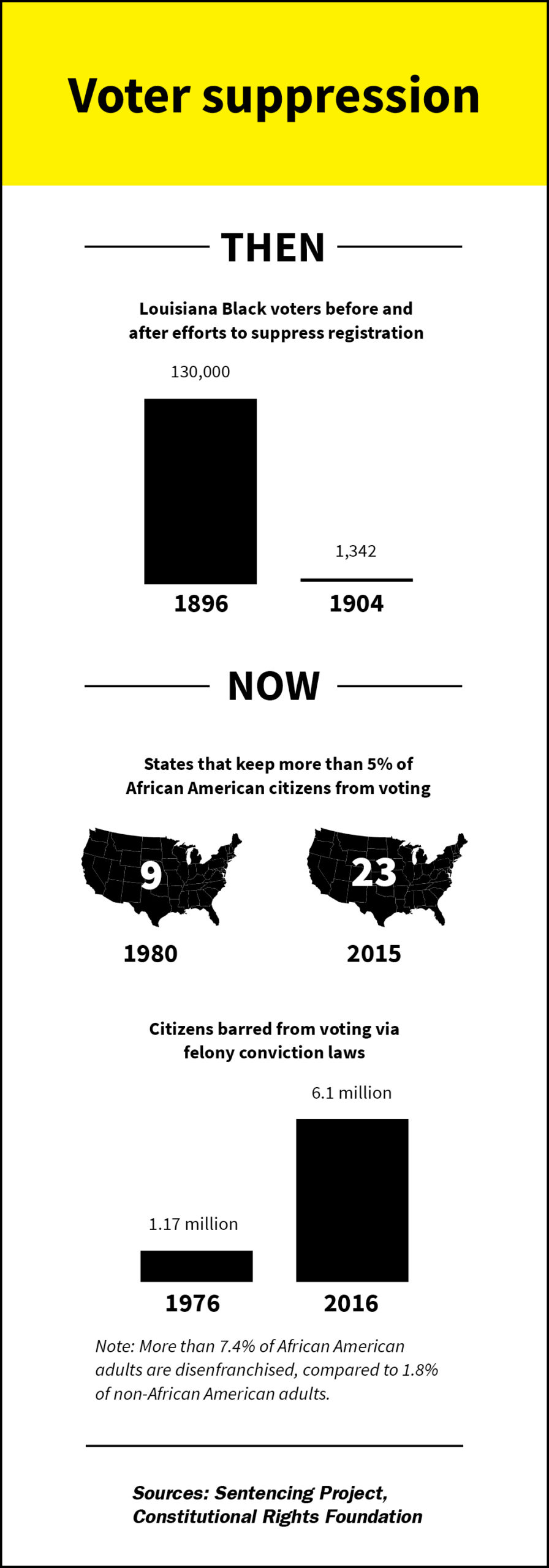

However, by the 1890s, several states had enacted poll taxes, literacy tests and used violent intimidation to disenfranchise Black voters.

Meanwhile, Black women were still battling for their voting rights. Abolitionist, feminist and ardent anti-segregationist Mary Ann Shadd Cary became the first African-American woman newspaper publisher and editor. Responding to Douglass’ call in 1848 for suggestions to improve the lives of Black people, she wrote, “We should do more and talk less,” in a letter that helped galvanize the male-dominated, anti-slavery establishment into taking more action. She openly defied the Fugitive Slave Act passed in 1850 and encouraged former slaves to flee to Canada.

A former slave, Ida B. Wells — a gifted journalist and fervent abolitionist — reached fame for documenting lynchings, fighting for the right to vote and advocating for Black women’s equality in the late 1800s. She famously refused to be relegated to the back of the march for suffrage, joining with the delegation of white women from Chicago instead.

Once women attained the right to vote, they significantly helped swing elections in favor of Black men. But it was a constant struggle, fighting decades of violence aimed at suppressing the Black vote. As recently as 1964, only 2% of Selma’s eligible Black residents were registered to vote despite their legal right to do so.

One calendar year later — after decades of cumulative risks, lives lost and organizing having gone into the effort — the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed.

And the battle continues. In 2013, that act was weakened by the Supreme Court, and states have since passed new laws restricting voting rights disproportionately for people of color.

Today, Black leaders are still fighting for people’s rights and making history. In 2018, Joe Neguse became the first African American person elected to Congress from Colorado. He also co-founded New Era Colorado, which registered 150,000 young voters.

At SEIU Local 1000, we use our hard-earned voting rights to ensure our elected representatives reflect our priorities, including the right to join a union, ending structural racism, health care for all, and the right for immigrants to live and work free from intimidation and fear.

Local 1000 members themselves make this happen by reviewing candidates’ positions, conducting interviews, volunteering for our endorsed candidates to help them get elected, and meeting with them regularly once in office.

While much work remains to be done, we will continue to lift up those who suffered and lost to put us in a position to win.

President,

SEIU Local 1000

PHOTO COURTESY OF SEIU local 1000

Be the first to comment on "Yvonne R. Walker: Celebrating hard-earned rights"