By Casey Rafter

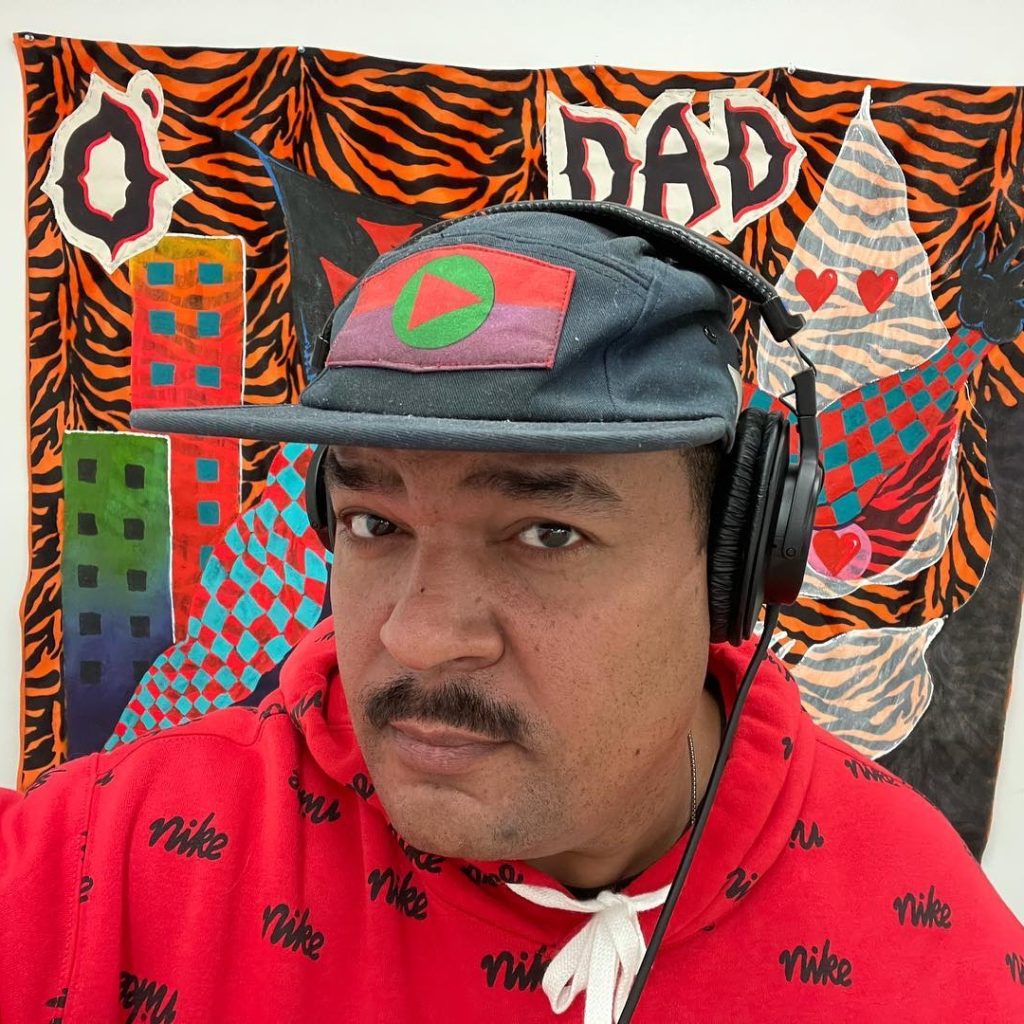

Tavarus Blackmon (aka Blackmonster) is a Sacramento talent who’s dipped his toes in music, fashion, collages and curations. His art has been seen digitally and in the real world at Crocker Art Museum, Axis Gallery and on his website, which tantalizes visitors with vibrant colors and themes. Blackmon teaches artistic methods at Sacramento State and has taught at UC Davis, which is also where he got his master’s degree in fine arts.

Andru Defeye is a celebrated local hip hop artist and a self-named guerilla poet who energetically supports the artistic community in all its forms. In 2020, Defeye was granted the title of Sacramento’s Poet Laureate. In addition to being the former communications director for Sol Collective, Defeye founded performance art crew and support system Zero Forbidden Goals. In 2023, Defeye was given a key to the city of Sacramento.

The generous folks at Sac State’s KSSU once again opened up their space for Blackmon and Defeye to meet face to face in the quiet studio. They’d been in the same room before, but this was their first chance to chat. This piece is part of the Creativity in the Capital podcast series.

Defeye: I’ve been in Sacramento since 2009, came from San Francisco. … I grew up in [the] Manteca, Stockton area, and there is no arts and culture there. Then I went to San Francisco where it was too much. I was in entertainment at the time, and just the drug, sex and rock and roll of it all was a little wild. Ended up in Sacramento and was like, “Oh, this is great.” Sacramento feels like a place where you can make your own lane and do your own thing. You don’t have to follow someone else’s path.

Blackmon: I’ve been in Sacramento my whole life. My family lineage goes back, at least to my great grandparents who emigrated from Sicily. … So I have family photos from V Street in the early 1900s, my grandfather and aunts and grandmother. I live in the same neighborhood. I just have felt absolutely connected to the vibes of living in a place where people I’ve been related to have died over the last 100 years. … At times, it’s felt like I would question if there’s enough for me here, and I’ve never really wanted to be or go anywhere else. I’ve gone places and done stuff to make art, and none of those situations ever made me want to leave where I’m at.

Defeye: I got here 15 years ago, about, and I’ve seen the city change from my vantage point. Has there always been the arts in Sacramento? Have you seen a change? What do you think from when you were growing up to now?

Blackmon: I was not into art before 15 years ago; I didn’t start really getting into art until 2010. I was in the first year of the pilot film program here at Sac State, and got together with my wife. … And in that time, I just bought a guitar, an amp and hella canvas and a tattoo kit. Let’s just do it, you know?

Defeye: So your whole life started.

Blackmon: Then we have a kid right after that. [I started] painting probably around 2010 in my kitchen with my daughter and [my wife] and just kind of built up from there. In the last 15 years, has it changed? … It seems like it has changed from the new buildings on campus, the new art sculpture lab, access to more classes on campus, all of the pandemic relief funds that were made available to the creative economy through the state government. … I’ve totally benefited from all that. I feel like I didn’t just benefit, I worked hard, and I put everything into my business, which is to say, I didn’t take any profit. I just reinvested 100% of everything I’ve earned, in addition to buying a house and paying bills and stuff. Yeah, I don’t care for much else other than making more work.

Defeye: I love being around the world, but this always feels like home. I always tell people, if I leave Sacramento, it’ll be for an island in the Caribbean — the only other place for me is somewhere with sandy beaches and warm water. Because there is so much opportunity to just create your own lane. … I feel like Sacramento has always embraced that for me. This last October, they gave me a key to the city. So it definitely feels like home. I haven’t figured out what that key opens.

What would you consider your field?

Blackmon: I am an artist. That’s how I’m trained. I have a bachelor’s degree in film production and a master’s of fine art. So I feel like my kind of purview is the wider field of the arts. But interestingly enough, the arts have brought me into other fields like finance and investment and government opportunities. …

Defeye: Does everyone in your field have what they need to make success a reality?

Blackmon: No, not really, they don’t. … I feel like I’m representing not just the arts, but humanity, culture, society, different things like that, that have connections to state and local governments, nonprofits, board of directors, volunteer opportunities, consultancies. As an instructor on campus here at Sac State, I feel privileged to be able to share things that I’ve learned. …

I was a non-traditional student. I was a little older, I have more life experience. Most of my students [now] are in their 20s, so they’re coming from a different perspective. I’d say, in order to really have what it takes to make it in the arts, you have to be cutthroat, but not in a way that you have to be mean or nasty. You just have to be willing to do the dirty work — stay up late, get up early, wash the dishes, cut the grass, feed the kids and make art every day. I couldn’t do that without my wife and my partner, who is an alumnus of Sac State, and the BFA program here, Elizabeth Kord. Between the two of us, we try to make everything work. …

Defeye: Yeah, you’re also an educator… I think a lot of us have to have another gig. As poet laureate — [the] city’s only paid artists on the city’s payroll — they pay me $3,000 a year. … I do a lot of consulting, I do a lot of graphic design, websites, content creation, but there’s always had to be something else. So surviving as a full-time artist and creative, I don’t know too many people [who can]. I know a handful that do it out here, but they definitely struggle. There are definitely months where it’s really tight. And some of them don’t have health care.

Blackmon: My daughter needs braces, so I work a lot. Work never stops, which is kind of cool. I think I learned that from my mom who worked around the clock in all kinds of different ways. I’ve come into contact mostly with folks who pursued professional degrees in art. That kind of association means that those folks, in many cases, went on to teach or have positions at galleries or museums, whether they have kids or families or not. They’re self-sustaining, they’re independent and they’re promoting and cultivating art in the region. … I think it’s not just about being an artist, I have the desire to learn stuff. Curiosity is a big part of being an artist. You can’t knock someone who makes it by their own means. …

At 22, I matriculated. Didn’t take long for me to decide I wanted to change everything, which meant I had to do something I never really considered doing, which was being responsible. And I don’t want you to get me wrong, just going to school is not a responsible thing. People who make it or do this or that on their own means, it takes a lot of responsibility. For me, I needed more structure. … I have to have something concrete, especially now being a dad. I never thought I would be a dad. But when I had the opportunity, I really wanted it.

Defeye: Discipline, discipline discipline. … I’m someone who barely graduated from a continuation school, went to junior college for two weeks, and was like, “I really like my philosophy class, but that’s it,” and dropped out. I knew I wanted to do words; that was part of my issue in school, among other things. I failed algebra four times, because you couldn’t tell me that I needed it because I was going to be a writer. So I’ve gone on to work at newspapers and publishing articles, because it was always words with me. But I knew, even if I wasn’t going to go to a traditional schooling route, I was still going to take writing workshops. I was still going to be in poetry workshops, sitting with folks who would redline my whole paper, “You missed the nut graph.” And I’m like, “Excuse me, what is that? You’re using vernaculars that I don’t know.”

Now I’m looking at what has me the most curious is the ways that people are pushing their art. I’ve been doing this for 20 years professionally. God, I sound old when I say that. It’s a different world. I remember the first record deal that I was ever talking to someone about was like, “We’ll give you this percentage of your brick and mortar and this percentage of your online.” Nobody was doing numbers online, it was just starting to become a thing. Now you’re seeing these artists come out that are breaking without any of this standard format. You don’t need a label, all you need is a good social media account that picks up like fire. Then all of a sudden, you can be out there doing what you used to need a label for. Some of these Gen Z kids, especially, are really figuring out how to work the system — because it’s curiosity.

Blackmon: I totally feel like folks have to do whatever it takes within legal business means. For me, organizing my work and activity into a corporate structure as I’ve done, it’s just totally been necessary. It would not have happened without the pandemic. I probably wouldn’t have even made the music I’ve made now without the pandemic. I think young folks who are wanting to make it in the arts, you totally can do it. You just have to be prepared to do a lot of work, which is fun.

Defeye: Yeah. What about [the] marketing part, [the] branding part, all the parts that aren’t fun to make it a sustainable thing? When I talk to young people about it, I’m like, oh, yeah, it’s fun to throw paint around on canvas. It’s fun to make beats and write rhymes and perform and be on stage. But you gotta get your bio right, you got to have a press kit, you got to have a website. I gotta hit up schools consistently to say, “Yo, I’ve got this program or this performance that I want to bring to you.” I’ve got to research who I’m gonna send that to. There’s so many moving parts of being a working artist that aren’t creating, unless you have something on the side, right? Like if you do have something that’s paying the bills, then you get a little more freedom to be just creative with it, versus having to be dependent on this art to make X amount of dollars. That takes care of my bills; otherwise, I’m out on the streets.

Blackmon: That sounds like gambling to me. I never gamble. What I do is I put my foot down and I walk a straight line. … I don’t necessarily make money from my art. I make money from my work, which is a part-time lecturer in the CSU system. All the work that I make makes me eligible to be an employee in the CSU, but I don’t get paid for that work. I don’t get credit for it here [at Sac State]. Only thing that matters here is that I care about my students, that I work as hard to be an instructor as I am as good an artist. I feel that’s a good thing.

Not to say I don’t make anything from art: I make nominal monies, grants, business loans, $5 every other month from SoundCloud. That doesn’t sustain me. That might just kind of kickstart my next project. Because it’s all going to be reinvested into the organization. Because I’m my own boss, and an employee in the CSU, I could do whatever I want with the work I make, which is totally cool. How to make money at art? You just have to make art long enough and you get good enough, and people will want it. …

Defeye: I feel like the academic art world, and the street art world have always been very separate and almost combative in my experience. I have this fancy title now of Poet Laureate, so I’m allowed into some of these academic spaces. I’m actually a fellow of the [Academy of American Poets], currently having conversations around hip hop. Then they’ll say that hip hop, that’s rap, that’s not poetry, and they’ll try to keep it outside of the academic realm. When in reality, something like rap and hip hop culture is probably the most widely universally known form of poetry over the last 50 years. So I feel like those things have always been really combative; the academics trying to keep the street out and the street not really respecting the academics. Because of that, there’s resentment that builds up between the two.

I wish, and it’s part of the work that I’m trying to do now, to bring everybody into the same space to really respect the hustle. I got friends who been around the world doing rap music that never spent a day in school. I’ve also got folks who have MFAs who I’m just like, you’re making some of the coolest [art] I’ve ever seen. So I think it’s almost like we’re pitted against each other. … How do you feel about that?

Blackmon: I never really got involved in it, because I’m not [an] art stakeholder. I’m a crypto stakeholder. … As far as graffiti and street art and fine art, I just say, who cares? Go to art school and just do graffiti, or don’t go to school and make Flemish paintings. Why not? I care less about things like that because I have no investment. I have no investment in street art even though everything that I was doing up to the time when I got into grad school was spray paint and dripping paint and things like that. By the time I graduated, I just felt like I’m multicultural and multifaceted, experienced duality, experienced multi-dimensional time through improvisational practices.

Defeye: Some of the work that I’m talking to young artists about constantly, too, is: How do you put the proposal together for the grant that gets you paid? Because it’s not always about whose work is the most impactful? … You know, I worked at Sol Collective for 10 years, and what the young people they don’t always understand, especially if you’re Black and brown, you’re just being and creating is resistance, and is social justice, you having a voice via social justice, it doesn’t have to be protest art, there’s so much that goes into it, and then understanding how to talk to them about your art.

Because we can feel about our art how we want to feel about it, but in order to get the money that they’re holding onto … how do you appeal to those folks? How do you appeal to whoever’s on the grant panel? It’s all kind of luck of the draw, who’s even on the grant panel.

Blackmon: I would say, you just have to, like, apply yourself. That’s what I did. And I did it, when I wasn’t even good. I’m good now. …

How do you feel about Sacramento as a cultural hub? And then how do you place your work within that, whatever that paradigm is?

Defeye: Sacramento is finding its culture. And I think it depends on who you ask. There’s a little bit of a culture war going on in Sacramento. If you ask the politicians, for the last eight years, at least, [it] has been, “We’re going to be a world class city. We’re going to be the next Austin, we’re going to be the next LA.” If you ask the artists on the ground, or Sacramento, and we’re proud of being Sacramento, we’re where the Art Hotel happened, where Black Artist Foundry happened, we’ve got some amazing arts movements and an amazing art culture on the ground.

Sacramento loves to tout its diversity. We [were] the most diverse city in 2005. [We’re] in 2024 now … and Sacramento is hella segregated. So our cultures are in pockets that don’t always come across each other. … That’s a great thing that art does is bring different cultures together and introduce them and create intersections in poetry. And in the hip hop community. There are artists from South Sac who don’t come to Midtown, there are artists in Del Paso that don’t come to Midtown. There are these hubs of arts, per community, per neighborhood that don’t always know about each other. There’s a tendency also to be like, Well, if you’re not in Midtown, then you’re not an artist, the art scene is in Midtown. And I don’t really buy into that. …

You couldn’t book a hip hop show, in a lot of these venues, especially in Midtown, the insurance is still super high, like when you do a hip hop show versus doing a rock show or a country show. And that’s because racism is real, and alive and well in Sacramento.

Blackmon: Doesn’t that make the hip hop show more exclusive?

Defeye: I think it just puts this barrier. Like I remember being 20 years old, and I want to do [a] hip hop show in the Bay. And there were 15 different places I could call. And they would say, yeah, absolutely come and do it. … So [in Sacramento] we started doing these things called guerilla art flash mobs. We had a hotline, and people could call up to the hotline, find out where we were going to be on Monday night, 8 p.m. And we went into businesses that wouldn’t allow hip hop, or didn’t traditionally have hip hop, and we frequented the business. … That shifted the culture where these businesses started allowing hip hop. You got 50 to 200 people on a Monday night in your venue because of hip hop, then you start thinking, businesswise this is a good investment. Hip hop is good for business.

How do you feel about the community, and how are you a part of it as someone who’s biracial? How do you feel about the community as a whole, and it’s racism in the arts?

Blackmon: I don’t really attribute any of my shortcomings in the arts within the region to my Blackness. My work is who I am. … I’ve been able to work and in my own way, do what I want. I’m still able to make whatever work I want. … Whatever the story is, I feel like I’ve done my part to write stories about Sacramento, because I feel like stories of Sacramento have always disappointed me, and I’ve ever been represented within them — you know, the story of Sacramento and the culture. … I feel like it’s still being written, I plan on being a part of that wider, broader discussion. …

I’ve experienced a lot of racism. And it always made me a little more chipper, because it’s like, I know what I’m fighting for, in my own space. … I feel like folks maybe worry too much about racism. I’ve never had a Black teacher. But I’m a Black professor. I still got here. Still as Black as I ever could be, but I talked to some of my contemporaries. They’re like, “You never had a Black teacher? Like, how’d you do that?” And I just say, “I don’t know what the answer is. I guess I’m just Black enough to be myself wherever I go.” And I feel like folks should really value themselves for who they are, which in most cases is good people. And the racist world that’s on the television is not part of my daily life. I like my coworkers. I respect their work. I like the people who I learned from. Hell, I had a few bad teachers. But for the most part, professionally, it’s been a nice experience. …

But it’s not the same for everybody. Not everyone feels the same way. I just want to always do my best, which means that no one could tell me that it’s not good enough.

Defeye: Do you find that any part of your creative work functions as a therapy or a way to process trauma? You were talking about past transgressions. Is there a part of your work that’s self healing?

Blackmon: Yeah, totally. So in my work, I talk about this theme of heart and dagger. I’m a survivor of open heart surgery and I experienced a punctured left ventricle when I was 20. And I really had to build up my life from there, 2-hour bus rides just to get a doctor’s appointment just to talk to someone and get some meds. I’ve made that a major part of my work. I’ve made the joy I’ve experienced as being a dad and father, the domestic life a major part of my work, because I’m grateful and thankful having survived painful, horrible trauma in my life.

But it wasn’t like, I was like, hey, I’m an artist, I’m gonna talk about this bad stuff. It just [happened] organically. Years after the event where I had open heart surgery, I never told anyone that that happened. The first person I told was a professor, some 10 years later, after I had my first kid, art has been able to give me space to talk about like what’s most painful, and ironically, also the most beautiful part of my life realization, ascension, or whatever that could mean, as beautiful as moving on to the next stages of consciousness just by taking out the trash can anyone could do that? That’s beautiful, it is painful and hard to kind of discover it. If you have a good teacher, maybe they can help you with that.

Defeye: I think that’s how we keep ourselves alive and thriving through this art. So I have a medical condition where I was born without stomach muscles, told that I wasn’t supposed to live past a certain age, they told me when I was 16, that I wasn’t supposed to make it past 15. Often, when I go into classrooms and talk to young people, I’ll tell them that I wrote myself into existence. My first poems weren’t poems, they were just me trying to be and trying to get all of this negativity out of me. So it lived on a paper instead of living inside of me.

I relate really heavily when you live through something that is life-threatening, the ability for art to help us rebuild ourselves and find just a place to put some of that as well. Also, you said it was 10 years before you really talked to someone about it. This condition was something that I hid from everyone I knew, for years, probably a decade, at least, of making art. But then I ended up writing a poem all about it, that ends on a very high note of like, oh, just keep the faith. Like, I’m still here.

I’ve danced across stages all around this country. And they said, I will never walk. So, I definitely share that same healing yourself through the arts and just finding a place to put all of it. My father passed away in June, and a couple of weeks ago, [I] wrote the first thing that I’ve written since his eulogy about him, and it felt like it had just been brewing inside of me, and was waiting to come out in an artistic way in this like, really thoughtful way, where before, it was just like, oh, just have a day where I would sit and cry. Or I’d listen to music that he used to listen to, and just miss him and hurt because I knew I needed to get that out. But this process of letting it stew, and then finally getting to a place where I’m like, Oh, I can pull this out and make something beautiful out of it. Instead of just having it be hardcore grief and tears, you know?

This story is part of the Solving Sacramento journalism collaborative. Solving Sacramento is supported by funding from the James Irvine Foundation and James B. McClatchy Foundation. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, Capital Public Radio, Outword, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review, Sacramento Observer and Univision 19.

Be the first to comment on "Creativity in the Capital: Tavarus Blackmon and Andru Defeye on the realities of making a sustainable living as an artist "