By John Patrick Leary

The evergreen questions raised by the label “conservative” are: Conserving what and from whom?

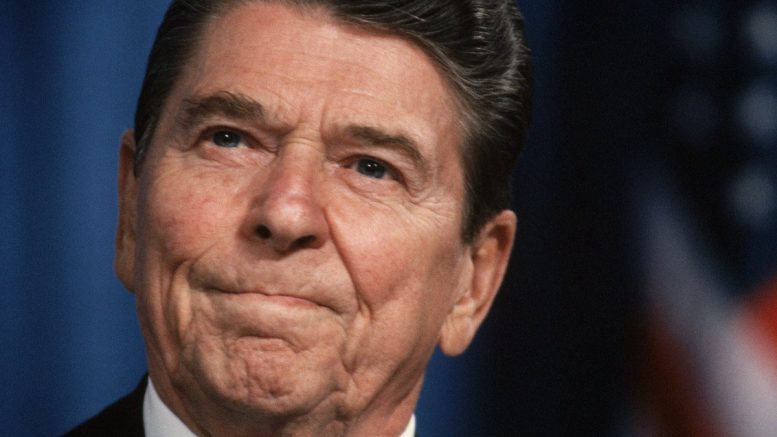

Let’s dispense with one popular answer to this question, asserted by many American conservatives and liberals alike: that proper conservatives are devoted to “small government” or engaged in protecting “individual liberties” from a big government. These are slogans of today’s Republican Party, but there’s no good argument to believe that the party behind the War on Drugs (Richard Nixon, and later Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and every Republican since), the PATRIOT Act (George W. Bush), the first and second Iraq War (Both Bushes), massive police funding, eliminating the right to abortion, Don’t Say Gay laws, and school book bans is, in any way that makes sense, devoted to “limiting” the power of the government. To make sense of the word “conservative” we have to dig deeper than headlines and slogans.

Like a lot of our political vocabulary — see also: “left” and “right,” — the political meaning of “conservative” came as a result of the French Revolution of 1789, when democratic radicals deposed the monarchy and the aristocracy. Soon after, in 1818, defenders of the French Old Regime founded a pro-monarchy journal, Le Conservateur, that first used “conservative” in the modern, political sense. The magazine listed what it stood for in its first issue: “religion, the King, liberty…and upstanding people.” These were the things under threat from the new society formed after the Revolution.

Modern-day conservatives don’t necessarily want to protect or “conserve” the same things as their 19th-century brethren. (Not too many Americans will admit to being monarchists.) But they do share a fundamental dilemma with their French forebears: Defining yourself in terms of an old order and its enemies makes it difficult to explain the sort of future you want to build. On one hand, conservatives defend tradition and duty; on the other, the definitions of these things shift with every generation. And what good is a tradition if it changes all the time?

In 1790, the Irishman Edmund Burke authored Reflections on the Revolution in France, a polemic against the revolution that has become the foundational text of English-language conservatives. Burke didn’t share the backward-looking attitude of Le Conservateur. Burke conceded that societies needed to transform over time, but he argued for a principle of social change that followed the examples of changes in “nature” or families, that is, slowly, over generations, and never all at once. Burke thought society should “conserve” what is worthy about past traditions, making judgments about what should and should not endure. (I’d note this is the difference between a preservative, which preserves something, whether it be strawberries or something else, just the way it was, and a conservative, which conserves something about it.) As Burke wrote, “A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation.” In other words, a society and its traditions cannot endure unless it can also change.

This brings us back to the original question: What should change and what should endure, and what is the principle by which one decides? Again, conservatives face the problem of defining themselves negatively, against what they dislike. “Liberal,” by contrast, takes its name from a positive ideal — liberty. “Conservative,” much like “progressive,” names only an attitude about political change over time. In 1960, the economist Friedrich Hayek, who many people would describe as politically conservative, wrote an essay titled, “Why I Am Not A Conservative,” in which he argued that conservatives had not overcome this basic problem. “By its very nature,” Hayek wrote, conservatism “cannot offer an alternative to the direction in which we are moving.” It defined itself only against other political identities, he wrote, decrying what it is against without offering a positive direction of its own.

Political scientist Corey Robin has recently argued that conservatism’s most consistent traits are 1) a veneration of hierarchy and order and 2) a fear of the lower orders. “Though it is often claimed that the left stands for equality while the right stands for freedom,” wrote Robin in his 2011 book The Reactionary Mind, “this notion misstates the actual disagreement between right and left. Historically, the conservative has favored liberty for the higher orders and constraint for the lower orders.” And, he goes on, it has historically defined itself against the movements it opposes.

To be fair, all political persuasions define themselves, in part, by what they are against. But it’s especially true of conservatism, whose very name signals commitment to conserving something being lost or taken away. This helps explain the never-ending identity crisis that shapes so much of the culture of American conservatives, which is engaged in constant arguments about what it means to be a true conservative (and the confessional mini-genre of articles called, “Why I Am A Conservative”). It also explains why so many on the right battle phantoms like “wokeness,” “critical race theory,” or the “gay agenda,” forever seeking new enemies to define themselves against. Seeking a more positive definition, the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) defines conservatism as “the political philosophy that sovereignty resides in the person.” Unfortunately for CPAC, plenty of political philosophers would say this is also a definition of “liberalism.”

One of the most eloquent rejoinders to the veneration of tradition in conservative thought comes from the American revolutionary Thomas Paine, who criticized Burke’s opposition to the French Revolution. What, Paine asked, are you actually for? Like American conservatives who proclaim their commitment to “conservative values” in a society riven by inequality, fear, and violence, Paine thought Burke was enchanted more by talking about virtue than he was by building a society that supported it. Burke “pities the plumage,” wrote Paine, “but forgets the dying bird.”

John Patrick Leary is a columnist at The New Republic and author of Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism (Haymarket Books 2019). His writing has also appeared in Guernica, The New Inquiry, and The Baffler.

This article was produced with support from a journalism nonprofit, the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. It was originally co-published in Teen Vogue.

This essay accurately defines what conservatism was before the Tea Party and Trumpism. Neither is conservative in the old terms. George Will, one of the clarion voices of conservatism in the past, argues that there is nothing conservative about Trump or his followers. They propose to tear down the old order, not to restore it. The express hatred of the “administrative state,” which is Newspeak for any government agency that stands in the way of what Trump wants. Like fascists of the 1930s, Trump and his allies express contempt for democracy and the rule of law, claiming that he is above the law. Since the Republicans do want to officially endorse fascism, they work hard at contorting Trumpism into a new form of conservatism that will conserve the original Constitution, as it was originally intended exclusively for white men. As George Orwell warned us in an essay “Politics and the English language,” the sort of doublespeak that clouds political meaning prevents all serious discussion of issues. We should be wary of using the term “conservative” to apply to Republicans who support Trump. They have abandoned conservatism. It is hard to locate conservative voices today.