In 1851, someone went into the food and hospitality business who was notorious for his culinary predilections

By Scott Thomas Anderson

He was viewed as the beastly outcast of Sacramento’s first frontier town – a man who’s forbidden cravings once made snow-stepping rescuers shudder with revulsion.

He was also the Capital City’s first controversial restaurant owner.

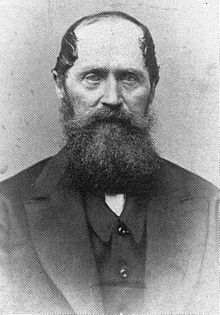

Lewis Keseberg was 30 when he first immigrated to the United States from Prussia. He landed in Cincinnati around 1844, where it’s believed he carried on the traditions of his homeland by working as a beer brewer. Within two years, Keseburg had joined a group of 81 migrants, which included a number of families, who were heading out across the Western expanse. The group would become known as The Donner Party.

Following propaganda and homicidally reckless directions from an explorer named Lansford Hastings, the travelers badly miscalculated their journey through the Sierra Nevada and ended up stranded near today’s Donner Lake. They were trapped there during the most-brutal snow season the state ever recorded.

In April 1847, a group of rescuers fought their way through the tail end of a blizzard to reach The Donner Party’s camp. One of these men, William O. Fallon, wrote in his journal what they discovered.

“Entered the cabins, and a horrible scene presented itself—human bodies terribly mutilated, legs, arms, and sculls, scattered in every direction,” Fallon jotted. “One body, supposed to be that of Mrs. Eddy, lay near the entrance, the limbs severed off, and a frightful gash in the skull. The flesh was nearly consumed from the bones, and a painful stillness pervaded the place … We delayed two hours in searching the cabins, during which we were obliged to witness sights from which we would have fain turned away, and which are too dreadful to put on record.”

Faced with the horrifying evidence of what hunger and want of life had driven the some in the party to do, the rescuers continued on with their mission to find those who could be saved. Fallon would describe how his companions willed themselves forward, looking for survivors.

“At the mouth of the tent stood a large iron kettle, filled with human flesh, cut up,” he detailed. “It was from the body of George Donner. The head had been split open, and the brains extracted therefrom, and, to the appearance, he had not been long dead—not over three or four days, at the most.”

A detail that clearly grabbed Fallon’s attention was that, inside this same room where George Donner was splayed out as a meal, there was also perfectly good animal carcass preserved, which no one had bothered to prep or cook.

“Near by the kettle stood a chair, and thereupon three legs of a bullock [steer] that had been shot down in the early part of the winter, and snowed upon before it could be dressed,” Fallon recounted. “The meat was found sound and good, and, with the exception of a small piece out of the shoulder, wholly untouched.”

Crossing through the snow to another camping area, Fallon and friends eventually came face to face with Lewis Keseburg. Fallon’s memory of that event would leave a haunting impression for generations of Californians.

“We went direct to the cabins, and, upon entering, discovered Keseburg lying down amidst the human bones, and beside him a large pan full of fresh liver and lights,” the rescuer documented. “Mrs. Donner, he said, had, in attempting to cross from one cabin to another, missed the trail, and slept out one night; that she came to his camp the next night, very much fatigued; he made her a cup of coffee, placed her in bed, and rolled her well in the blankets; but the next morning found her dead. He ate her body, and found her flesh the best he had ever tasted. He further stated that he obtained from her body at least four pounds of fat. No traces of her person could be found, nor the body of Mrs. Murphy either.”

Keseburg was ultimately one of the 45 Donner Party survivors to make it to Sutter’s Fort alive. But what was in Fallon’s journal soon made Keseburg infamous, especially after the discovery of gold caused fortune-seekers to flood into the area from all over the world.

These days, the public’s knowledge of The Donner Party ordeal is greatly influenced by writer and documentarian Ric Burns, whose 1992 PBS film relied on towering California writers like Harold Schindler and Wallace Stegner to mediate on the meaning of the tragedy. When penning its narration, Ric Burns didn’t hold back about what Keseberg’s reputation was.

“Tamzene Donner’s body was never found – Keseberg confessed to eating her remains,” Burns wrote. “Alone among the survivors, Lewis Keseberg spoke openly of eating human flesh and was reviled as a man-eater and ghoul.”

This view matches perfectly with Truckee newspaper editor Charles McGlashan observed in Keseberg’s own lifetime, particularly in the years after the Civil War.

“He has been loathed, execrated, abhorred as a cannibal, a murderer, and a heartless fiend,” McGlashan admitted after interviewing Keseburg in 1879. “His cannibalism has been denounced as arising from choice, as growing out of a depraved and perverted appetite, instead of being the result of necessity.”

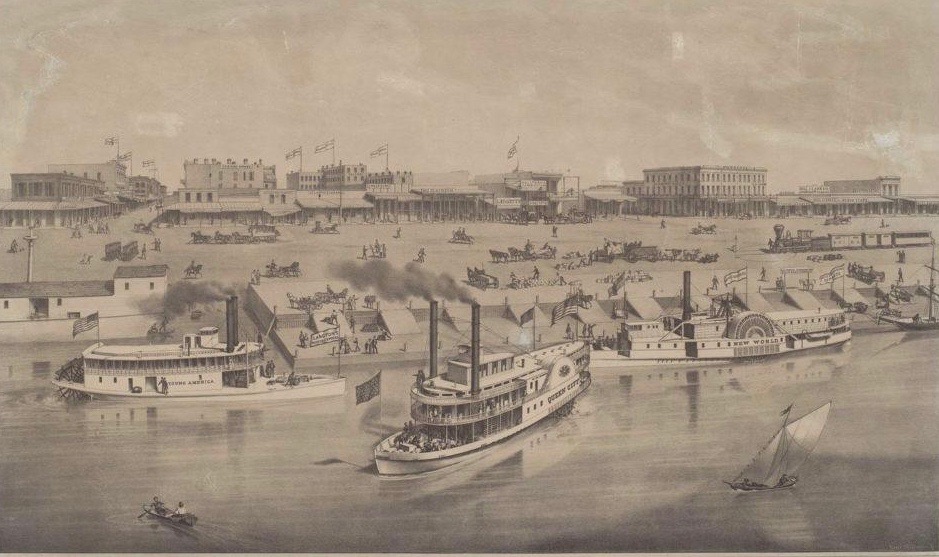

Despite Keseburg’s moniker as the cannibal of the Capital, he decided to open a restaurant along its bustling streets in 1851. His eatery was part of The Lady Adams Hotel. According to an 1852 ad in The Sacramento Union, it stood on K Street between Front Street and Second Street. City Hall identifies it has having existed where the second Lady Adams building now rises, which is part of Evangeline’s Costume Mansion. That means that original The Lady Adams gazed out towards the waterfront, which had its own reputation for mysterious murders back then (and related hauntings). Inside The Lady Adams, Keseburg the maneater – and possibly a staff – served dishes to whomever strolled through the swinging doors or took a boarding room upstairs. It’s not possible to know how many customers the business actually enjoyed. There’s reason to believe his clientele was limited: Around that time, a writer named Theodore T. Johnson noted the whispers, gossip and attitudes floating over Keseburg’s head in Sacramento.

“Within half a mile of our encampment, we saw the house of old Keseburg, the Cannibal, who revelled in the awful feast on human flesh and blood, during the sufferings of a party of emigrants near the pass of the Sierra Nevada,” Johnson put down in a travel memoir. “It is said that the taste which Keysburg then acquired has not left him, and that he often declares with evident gusto, ‘I would like to eat a piece of you;’ and several have sworn to shoot him, if he ventures such fond declarations to them. We therefore looked at the den of this wild beast in human form with a good deal of disgusted curiosity, and kept our bowie-knives handy for a slice of him, if necessary.”

Today, even the most temperamental, politically calculating or notoriously handsy restaurant owners in Sacramento don’t merit bowie-knives being carried in their establishments for protection. Or generally they don’t. In any event, Keseburg didn’t let these weapon-itching prospectors stop him from running The Lady Adams as destination for cuisine. This Halloween, while one can’t give a nod to Keseburg by having a meal inside of Evagenline’s, you can eat almost directly across the street from it at Willie’s Burgers, where melted cheese and grilled onions get thrown on stacks of juicy beef patties – beef being one of the meal options that was present at the Donner camp, which Keseburg passed up in favor of chewing on his human neighbors. Keseburg later switched to owning a brewery that was next to Sutter’s Fort. In 1856, he was arrested for assaulting one of his employees. The Sacramento Union described it as a case of battery.

But at least Keseburg didn’t eat him.

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the host of the ‘Drinkers with Writing Problems’ podcast, Episode 6 of which, ‘Boomtowns of the American West,’ covers writers who lived and worked in Sacramento and the Sierra foothills during the time of Lewis Keseburg.

Be the first to comment on "Unearthing the history of a real-life cannibal’s café in Sacramento"