How ‘Missing Middle Housing’ could help the city reach its goals

By Ken Magri

The task seems Herculean: Sacramento needs to add more than 60,000 housing units within the next decade.

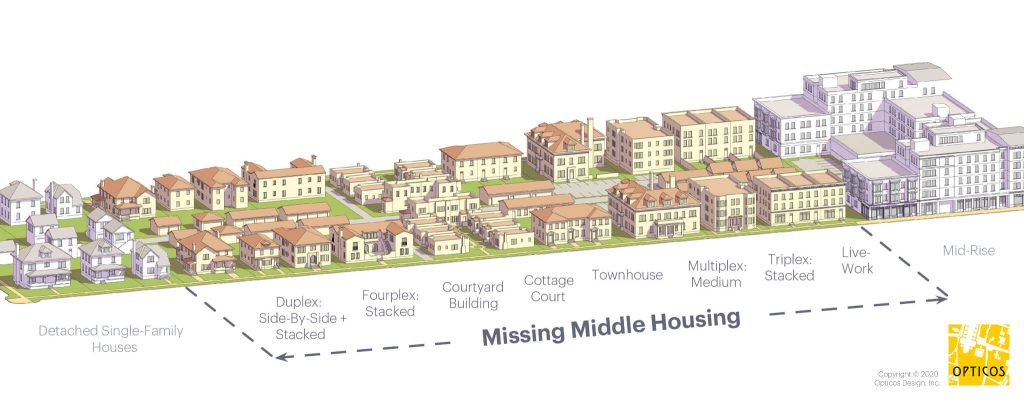

Part of the strategy for achieving this goal might lie in “Missing Middle Housing” (MMH), which describes a housing strategy that breaks away from the small occupancy of single-family homes and the density of high-rise apartments. The word “middle” refers to housing that fills a need somewhere in between those extremes by creating more affordable structures that are mid-range in terms of scale and type of building.

Duplexes, triplexes, townhouses and clustered cottages, once common in the years before World War II, all work within the MMH concept because they house more people on a parcel of land than a single-family home. But a large part of this strategy also includes building onto existing homes, like garage conversions, house expansions and Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), which are separate homes inside a backyard.

“The housing inventory is old,” said Jack Saba, co-founder of Bequall, a Sacramento ADU builder. “Not only do we need to address the supply of housing, we need to increase the options of housing so that people are in the right-sized homes.”

Saba was a guest speaker and vendor at the City of Sacramento Community Development Department’s public gathering in early October at CLTRE Club, which focused on the city’s approach to re-allow Missing Middle Housing as a way to get more homes built more quickly in face of the region’s affordable housing crisis.

Figuring out recommendations around MMH is critical as the city works on its General Plan 2040, which incorporates housing needs and includes the goal “to foster vibrant, walkable areas with a high-intensity mix of residential, commercial, office, and public uses, where daily errands can be accomplished on foot, by bicycle or by transit.”

During the October gathering, new MMH information and preliminary recommendations were presented from phase one of a year-long study with Opticos Designs, which partnered locally with Unseen Heroes, to get feedback on how MMH can positively affect Sacramento’s needs.

The city’s recommendations include: reducing lot setbacks by 25-50%; allowing lot sizes to be reduced to as small as 1,300 square feet (or a home as large as 1,000 square feet); promoting more trees along sidewalks and publicly shared spaces; increasing open space for multiple units over three; and redefining setback spaces to be open spaces in some conditions.

Also included in the recommendations were allowing second stories to be designed without further setbacks, reducing driveway widths, and sharing larger garbage and recycling front-load bins for multiple home lots. New privacy standards, like frosted glass, higher window sills, screening, offsetting windows and use of plantings were suggested, and a strategy to prevent displacement was also stressed.

But not everyone is pleased with the idea of more MMH. Even some affordable housing advocates argue that Sacramento’s preliminary recommendations are not equally applied to all neighborhoods, and could continue to discriminate between lower and upper income residents.

What makes MMH a better strategy?

Currently, the median price for a single-family home on an individual lot in the U.S. is $416,000, according to a Rocket Homes study. In California, the current average home value is $747,000. In Sacramento, the median price is $486,000, according to Redfin.

Traditional single-family homes have become increasingly unaffordable for many Californians, but especially those with lower incomes and people of color. In explaining why, Richard Rothstein’s 2017 book, “The Color of Law,” argues that single-family-only housing was adopted throughout the country as a form of passive segregation, making such homes affordable to whites only.

Across the nation, Black, Hispanic, Asian and Native American households continue to have lower homeownership rates than white households, according to the Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Middle housing homes could help close the gap. More MMH options could open up more opportunities for homeownership among people of color — and build generational wealth in the process.

The term “Missing Middle Housing” was coined in 2010 by Dan Parolek, a Berkeley-based architect and co-founder of Opticos Designs. Parolek said that his concept “is about adapting for your life. There is also a demand for it in walkable locations that are close to parks, retail shopping and mass transit.”

To blend in with such neighborhoods, Parolek said that any MMH structure should be “house scale,” meaning that its height, width and depth are similar in scale to single-family housing, “even though there are multiple units inside.” Parolek feels that this consideration about scale is important in conversations with community members.

In residential neighborhoods, Opticos advocates for buildings no higher than 2.5 stories. An additional half story under the roof gable of a two-story structure allows for more units inside, while keeping the building’s appearance at two-story scale. “There’s a huge difference in perception between 2.5 and three stories,” said Parolek.

“Missing Middle Housing” can get more people in secure housing by increasing the supply without needing new lots. When compared to a single-family home on a lot less than a quarter-acre in size, the MMH strategy could quadruple the occupancy by redesigning that lot into a two-story fourplex.

“Being more efficient with land, building more units on a lot, we call it ‘affordable by design,’” said Parolek. “This work that we’re doing with the city, if we can turn the right levers … like building four or five units on a lot versus one or two, it can deliver that sort of attainability to a middle-income household.”

An example of the state’s move toward MMH was the passage of Senate Bill 9, the California HOME Act, which went into effect in January 2022. The legislation makes it possible for homeowners to split their lots and build up to four homes on a single-family parcel. It also codifies state laws around ADUs.

But it’s precisely this aspect of MMH — increased housing density — that causes concern among some groups. Save Sacramento Neighborhoods (SSN), for example, has strongly argued against the city’s efforts to upzone existing single-family neighborhoods.

On the other self-proclaimed YIMBY side, House Sacramento issued an Oct. 11 statement highlighting several ways the city’s preliminary MMH recommendations don’t align with comprehensive affordable housing goals. For instance, in the statement, the group’s Communications Director Ansel Lundberg wrote that the recommendations continue to “leave in place the legacy of exclusionary zoning, with most incremental new housing development only allowed in historically redlined areas such as the Central City and North Oak Park.”

The affordability of ADUs

The MMH strategy attempts to address affordable housing needs by offering lower-priced alternatives — for example, through the building of ADUs. For its part, the City of Sacramento lowered the cost of building permits and fees on ADUs based on their size. It even offers free permit-ready architectural plans for studio, one-bedroom and two-bedroom ADUs.

Indeed, many of the vendors at the October event represented companies that build ADUs. Perhaps that’s because these units can be built faster and without any further policy changes by the city.

Rebecca Moller is the owner of SYMBiHOM, a Bay Area business that builds backyard ADUs. The models range from 500-square-foot studios up to 1,000-square-foot two-bedroom, two-bathroom units. The prices for the pre-inspected, prefabricated ADUs range from $150,000 to $250,000. While that may seem high, Moller said it compares well to the average cost of an ADU in California, which can run as high as $300,000 or more. And in turn, ADUs can generate rental income for homeowners. The rent can cover the owner’s mortgage payment each month while the home builds equity.

Earlier this month, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law Assembly Bill 1033, which allows cities to decide whether property owners can sell ADUs separately from their primary home. Proponents say the new law will help boost homeownership rates.

This story is part of the Solving Sacramento journalism collaborative. Solving Sacramento is supported by funding from the James Irvine Foundation and Solutions Journalism Network. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, Capital Public Radio, Outword, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review, Sacramento Observer and Univision 19.

Be the first to comment on "Is middle housing the missing piece in Sacramento?"