More than 1,400 markers across the state point the way to the past

By Richard Von Busack for California Local

Like religion, history often has to be taken as faith. The order of E Clampus Vitus, usually known as “Clampers,” is a mysterious fraternity dedicated to commemorating the parts of history that sometimes offend the local Chamber of Commerce.

This fraternal order has studded the state with plaques. In their spare time, they conduct their rituals in the Hall of Comparative Ovation with beards, candles and horns, mocking the mystic hoo-hah of lodge ceremonies.

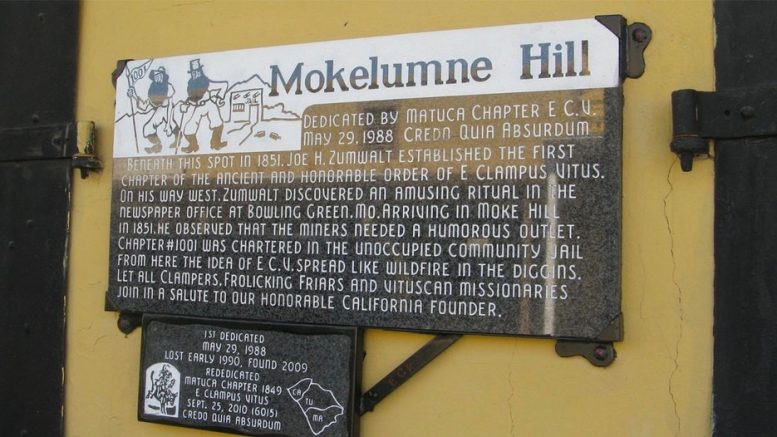

Their famous motto, which sort of dates to the early Church father Tertullian: “Credo Quia Absurdum’: “I believe because it is absurd.”

Like many of California’s immigrants, the Clampers headed west during the Gold Rush, shortly after its creation in West Virginia in 1845. The fraternal order flourished until around World War I and then later regrouped in the 1930s—a history documented in detailed accounts written in the 1990s and available on the Julia C. Bulette Chapter 1864 website.

E Clampus Vitus’ other creed, “Right Wrongs Nobody,” is a way of pointing out that official state markers tend to neglect the juicier side of California history. The Clampers point out local heroes and fairly benign episodes in the settling of California—as well as unforgettable disgraces, such as the sites of various California Chinatowns wiped out by racist mobs.

A Google Map created by the Billy Holcomb Chapter 1069 (based in Riverside and San Bernardino counties) has the index of items in the Clampers’ atlas of history. The volunteer-created Historical Marker Database offers an alphabetical list and pictures of not just the Clampers’ sites (the majority of which are in California) but also other pull-over spots throughout the USA.

Clamper plaques can be found across the state, commemorating yesterday’s famous bordellos, demised breweries, “hurdy houses” (taxi dance bars), frontier hellholes, and obscure battle sites.

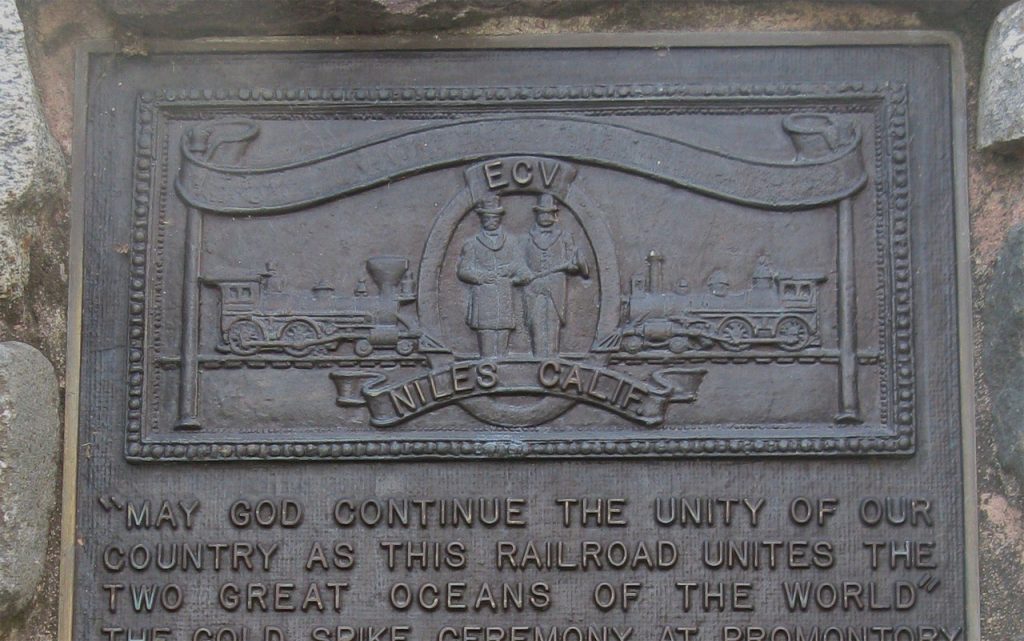

Everyone remembers the Golden Spike driven in at Promontory, Utah. Few remember that the last leg of the train voyage was the stretch from Sacramento to Niles. This quaint and barely changed town is where the transcontinental railroad really ended, near Jesus Vallejo’s mill on the banks of Alameda Creek, commemorated by an E Clampus Vitus plaque in 1979.

Joaquin Murrieta (1829-58)—called “The Robin Hood of the El Dorado,” fighting back against thieving, rapacious gold miners—is remembered at Joaquin Murrieta’s Well in the Contra Costa County town of Dublin. Though the facts about his life are in dispute, there’d be no Zorro without Murrieta, as surely as there’d be no Batman without Zorro. (The very good 1998 Mask of Zorro told the tale that Zorro was Joaquin’s avenging brother.) The Clamper chapter in Alameda and Contra Costa counties, which put up this plaque, is named in Murrieta’s honor. But like many frontiersmen, Murrieta was a multi-tasker; he had the legitimate business of rounding up mustangs and selling them to Mexico. (Murietta’s Well Winery is sited near where the outlaw used to water his green-broke ponies.)

In Sanger, a city in Fresno County, the Dalton Gang were routed by a posse from their Dalton Mountain hideout. The brothers had begun as marshals in the fictional Rooster Cogburn’s bailiwick in Fort Smith, Arkansas. But then the Daltons crossed sides and became bank and train robbers throughout the west. Chased out of California, they headed toward what would prove to be the last roundup in Coffeyville, Kansas, where this over-confident quintet of bandits tried to rob two banks at the same time.

Memorializing an exercise in futility is the Tolliver Airship plaque at the Livermore Airport, which commemorates an aircraft built about a year after the first flight at Kitty Hawk with $72,000 provided by Phoebe Hearst. Despite four engines and six propellers, the 250-foot craft never got off the ground.

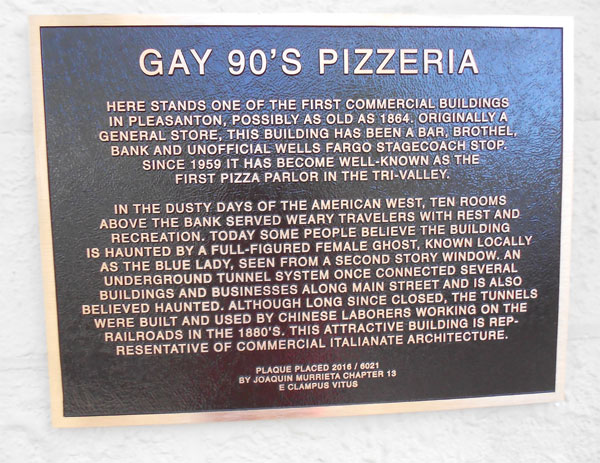

he more than 150-year-old Gay 90’s Pizzeria building in Pleasanton was the first pizza parlor in the tri-valley area…but before that it was also a brothel, a bank and a Wells Fargo stop. The Clampers’ plaque tells of subterranean tunnels used by Chinese laborers and a resident “full-figured” ghost called “The Blue Lady.”

The old expression among the pioneers heading to California was “we’re off to see the elephant.” One Clampus marker involves a dead elephant, a circus animal named Big Diamond buried near Eureka. Years later, it was dug up by amateur paleontologists who believed they’d found the fossils of a “Humboldt Mastodon.”

Take Mission La Purisima Concepcion near Winterhaven in Imperial County. A clickbaitist could make the case that it’s one of the ten worst missions ever! It lasted but a year: 1780-81; the settlers stole the best cropland and infuriated the local Yuma natives, and the “completely frustrated and disappointed” natives got some friends and destroyed the European outpost.

The Clampers are so busy commemorating everything that they even commemorate their own selves. The founding of the first chapter of the Clampers at Mokelumne Hill in Calaveras County is duly noted.

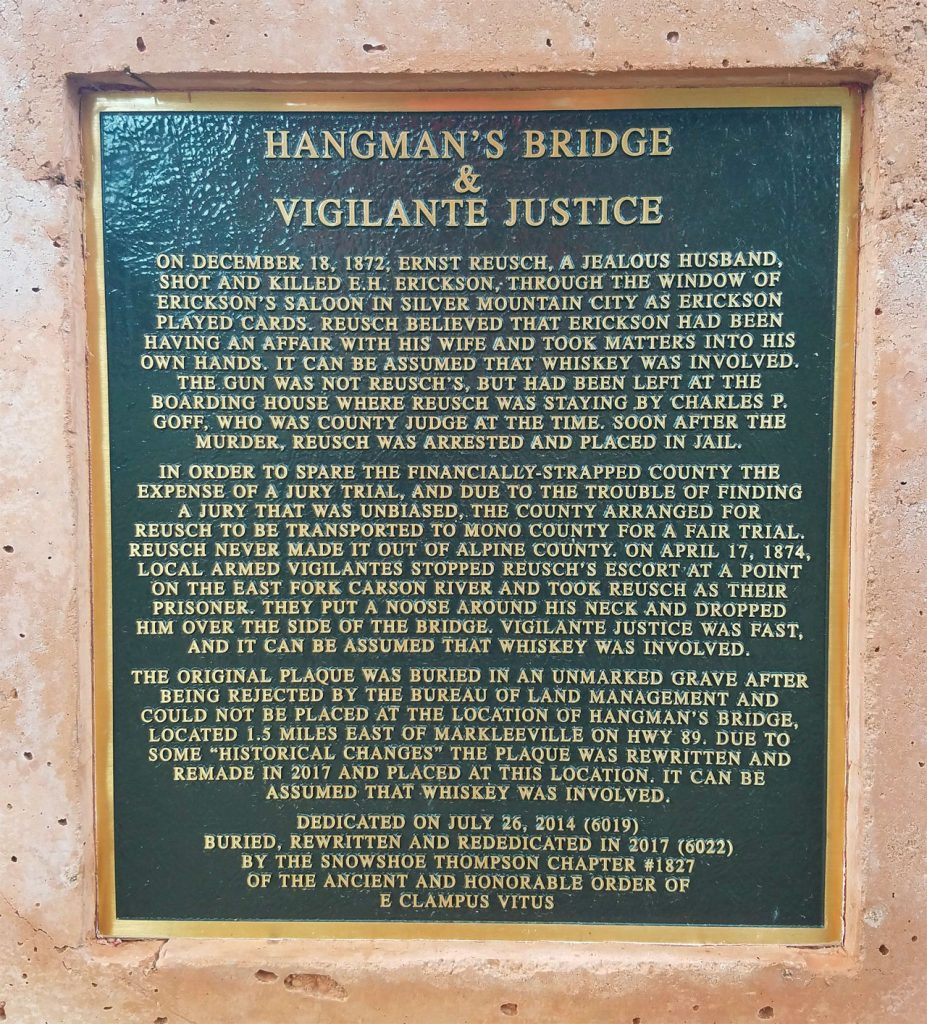

Hero Norseman “Snowshoe Thompson,” born John Tostensen, was for 20 years the only winter landlink between the Pacific Coast and the rest of the United States. “Snowshoe” invented snowshoes that were closer to skis—nine feet long and a source of merriment to townsfolk. Let them laugh. In winter after winter, he got the mail through the vast Sierra snows. The chapter of E Clampus Vitus active near Markleeville and Reno is named after this faithful Scandinavian mailman.

No historian can ignore the importance of alcohol. In rugged Markleeville is a plaque installed by the Snowshoe chapter that describes the lynching of an outraged husband named Ernst Reusch; he shot a man who was entertaining his wife and was hanged off a local bridge just outside Markleeville. So much for the unwritten law. “It can be assumed that whiskey was involved” both in the killing and the vigilante payback, notes the plaque, which was initially removed by the Bureau of Land Management.

Commemorated by the James W. Marshall Chapter 49 in the city of Plymouth is the D’Agostini Winery. This winery in the Sierra Nevada foothills is one of the state’s oldest—original vines and vaults have been in use since 1856, making it a year older than the Buena Vista Winery in Sonoma.

When in nearby Volcano, observe the plaque about the creation of Moose Milk, a milk punch topped with nutmeg, like a nog. Don’t tell a Canadian Navy man that we invented it, because they claim it’s as much their tradition as their motto, “Ready, Aye, Ready.” In their version, one “Moose Milk” ingredient is melted ice cream. However, there’s less controversy, and far less stickiness, about the claim that the Martini was invented in Martinez.

The Battle of Santa Clara’s legend will never be forgotten, because it was never really remembered in the first place. A small marker placed by the Mountain Charlie Chapter No. 1850 on El Camino Real in Santa Clara County enumerates the butcher’s bill in this last Northern California skirmish of the Mexican War, Jan. 2, 1847: “Dead none, wounded none, missing but one on the American side and he came up shortly afterwards stating that he had been searching for his ramrod which, in the excitement, he had forgotten to draw from his gun and fired at the enemy.”

Be the first to comment on "Marking the Spot: E Clampus Vitus maps our history"