San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Detective Jeremey Davis grew up in the same no-frills farming town as two of the state’s most inscrutable serial killers. They were men the Media hyped with unimaginative handles over the decades, but, from the lined orchards of Linden to the rusty barbed wire of Valley Springs, longtime products of Generation X simply refer to them as ‘Wes’ and ‘Loren.’ Wesley Shermantine. Loren Herzog. Two rough-neck country boys who managed to keep their savage secrets undetected in California for a dozen blood-soaked years. Davis grew up in Herzog’s neighborhood, though he’s a bit younger than both Herzog and Shermantine, whose predations immortalized Linden as a spot of intrigue for calamity jackals on the internet. The investigator agrees that’s an unfair legacy for the community of blue-collar walnut and cherry-growers he was raised with; though he and his partner, Detective Chris Sterni, also know why the story has an odd, algorithmic life online.

Shermantine and Herzog started killing in 1984, and all this time later, their total victim count remains unknown by law enforcement as well as how that elusive number might tie-in to unsolved killings from Reno to the Bay Area.

Davis and Sterni work within the heart of this mystery.

Assigned to cold cases, they’re tasked with reviewing every long-dormant murder investigation in San Joaquin County since the Beatles broke out on the radio. At least, every killing that didn’t happen in Stockton city limits. That means they’re working half-dead evidence trails from Clements to Tracy as they attempt to find straws in a population haystack of 460,000 people. And part of that job is understanding the grim truth about Shermantine and Herzog, especially how far their malevolent touch actually reached.

“There are a number of unsolved cases that could be them,” Davis observes. “That’s the difficult thing about our job. We’ve got to go by evidence. You know, you can speculate all you want, but if you don’t have the evidence to put it all together, it’s really hard.”

More than 12 years after Shermantine and Herzog’s last known burial site was uncovered, Davis and Sterni continue searching for evidence, primarily around a pregnant Jane Doe who was found in a ranch well in 2012 lying with two other victims. The effort to identify this young woman has gone nowhere. Now, one of the sheriffs’ last chances could involve a collection of battered items that were fished out of her burial soil. It’s a case literally dug up from the backhoe-broken earth of Davis’s hometown.

“If someone even thinks they had a family member who was in possession of these items, we want them to reach out to us,” Davis stresses. “We would still love to sit down and meet with them and discus what possibilities are there.”

Turning the corner on cold cases

A lot has changed since Shermantine and Herzog were first unmasked. The Linden bar where the pair targeted their final victim, Cyndi Vanderheiden, is now a public library. One of the key investigators who caught the duo, Stockton Police Detective Laurits “Pepe” Petersen, has since become a murder victim himself. Peterson was stabbed and then shot execution-style by a mentally ill man in 2016. His death was a psychic body blow to colleagues, particularly retired Stockton homicide detective Steve Knief, whom Peterson had helped with one of the most-frustrating cases of his career: That involved the disappearance of 16-year-old Chevy Wheeler. When Peterson started re-working Wheeler’s case again – originally Knief’s case – years after she vanished in 1985, it began tightening the proverbial noose on Shermantine and Herzog.

Not long before Cyndi Vanderheiden went missing from the Linden Inn, Peterson had submitted DNA evidence from a suspected crime scene in Calaveras County for lab testing. It came from a hunting cabin in the brushy hills behind San Andreas owned by Shermantine’s family. It was a place Kief had tailed the teen’s movements to after she first went missing from Franklin High School. Knief found blood and hair that matched Wheeler’s inside the cabin and was sure that then-19-year-old Shermantine had raped and killed her there. But no DNA procedures were used at this time. Detective Knief couldn’t get an arrest warrant. Knief went on to become a patrol sergeant, though Wheeler’s case kept bothering him. Later, around the time Shermantine was arrested in Calaveras County for abduction and rape in 1998 (charges he beat in a jury trial), Peterson decided to submit the old cabin’s blood and hair evidence for genetic sequencing. He got a direct hit. Wheeler had been there.

“At that point, they took me out of patrol, temporarily, and brought me back to work the case again,” Knief recalls. “I was partnered with Detective Peterson on it.”

The two Stockton police investigators were soon coordinating with a team of San Joaquin Sheriff’s detectives led by Deborah Scheffel. It was the group that would finally end Shermatine and Herzog’s 12-year tragedy run.

But for many of the duo’s victims, capturing them did not equal justice. To start with, Shermantine and Herzog have only been found guilty of murdering five of their ten known victims. And the question of their potential unknown victims is a cloud that’s never lifted from San Joaquin, Calaveras or beyond.

Herzog eventually killed himself at High Desert State Prison.

Shermantine is currently on Death Row, where he’s muddied the investigative waters with contradictory statements over the years, sometimes claiming he killed no one, other times suggesting that he and Herzog murdered as many as 72 people. Shermantine’s motives for boasting, or denying, appear to range from wanting prison perks to getting attention from female journalists. But the inmate hasn’t given law enforcement any tangible leads on his crimes since 2012, including details that would identity the pregnant Jane Doe in the well. In recent times, separating Shermantine’s culpability from his lies involves a lot of tail-chasing.

Then came the sea change. Joseph DeAngelo. Nothing was ever the same after him.

Joseph DeAngelo was a former Auburn police officer whose 12-year reign of murders, rapes and burglaries across California earned him the sobriquet the Golden State Killer; but what arguably marks the craven man’s place in history was how he was caught: DeAngelo was the first major case in which the familial DNA process was used to bring justice to a decades-old crime spree. The method allows detectives to compare DNA samples from their crime scenes to vast sample collections that were publicly uploaded to ancestry databanks, thus establishing direct cohorts of individuals who are genetically linked to their evidence. Though labor intensive, investigators can start finding and contacting people within that cohort to study their locations, timelines and alibies around a given murder. When a team of California prosecutors successfully used familial DNA to get DeAngelo sentenced to multiple life sentences in 2020, cold case detectives everywhere began learning the new technique.

That’s bred more than hope – it has bred results. Since DeAngelo’s arrest, Placer County authorities have used familial DNA to solve the murder of a newspaper reporter from 1985; the Sacramento Police Department has used it to unlock the slaying of a teenager girl in 1981; and the Sacramento Sheriff’s Office employed it to bring closure in the case of the brutal bludgeoning of a court reporter in 1970.

Sterni and Davis are now using the familial DNA process for much of their shadow-chasing in San Joaquin. There’s a lot of reasons, not the least of which is they have a ton of ground to cover: Sterni points to nearly 200 unsolved cases to work, around 20 of which are victims who have never been identified. The familial DNA process is also helping on that front.

“Sometimes we’re not even looking for suspects, sometimes we have a John Doe or a Jane Doe and we’re trying to do a familial DNA match just to find out who they are,” Davis explains. “Our main goal is to reunite these people with their families; and then once we get that, we can bring them some closure and let them know that we’ve found their family member. That’s when we start working to find out who did it.”

Sterni agrees, adding that, with the right scientific collaborators, they’re beginning to gain traction.

“We’ve been working with Othram labs in Texas and we’ve been getting cases back we’re they’ve identified bones and we’re actively working those cases,” he confirms.

However, considering the partners are investigating bodies that go all the way back to 1964, while the familial DNA technique may light previously and hopelessly darkened tunnels, there’s still no getting around the sheer time committed involved for each and every case that it’s applied to.

“It helps narrow it down, but we have to do all the backtracking – basically we follow the family tree all the way backwards until we find who were looking for,” Davis says. “It’s a lot of work. And you can imagine, over 20 or 30 years – if something has happened a long time ago – people who were in California have now moved to Texas, Florida, all over the United States. So, we’re reaching out all over the U.S. to get DNA samples from people to try to match the familial match that we’re looking for.”

In addition to all those factors, a large number of Davis and Sterni’s unsolved murders have a specific question mark hanging over them – almost all of them, in fact, that happened between 1984 and 1998.

Forgotten and from the ground

Shermantine and Herzog’s modus operandi changed over time.

Four of their early victims’ bodies were left out in the open to be found: Henry Howell, who’d been robbed and shot-to-death in the high Sierra; Howard King and Paul Cavanaugh, who were killed in hail of bullets near the Delta; and Robyn Armtrout, who’s mutilated remains were left in a creek bed near the Calaveras River. Around the time that Armtrout was killed, Shermantine and Herzog appear to have started mainly targeting women – and working much harder to hide their bodies.

The pair are known to have two secret burial spots that were eventually discovered, mostly through help of Shermantine himself. One was the ranch well outside of Linden. That’s where the bones of Kimberley Billy, JoAnn Hobson and the pregnant Jane Doe were ultimately recovered. The seasons have changed many times since, but the lost, would-be mother remains nameless. Her bones have now been studied by Chico State professor, Dr. Eric Bartelink, whose forensic anthropology team has helped other law enforcement agencies break numerous cases. In recent years, that has included helping Roseville police detectives solve the murder of John Alpert, and Place County Sheriff’s investigators solve the slaying of Trang Tran.

Sterni notes that Bartelink’s examination of the mysterious woman and her fetus has provided details to work off.

“He’s saying that the unknown female is going to be 16 to 21 [years old], and approximately five-foot-seven, give or take four inches,” Sterni notes, “and then, the fetus, he’s estimating to be 36 fetal weeks old.”

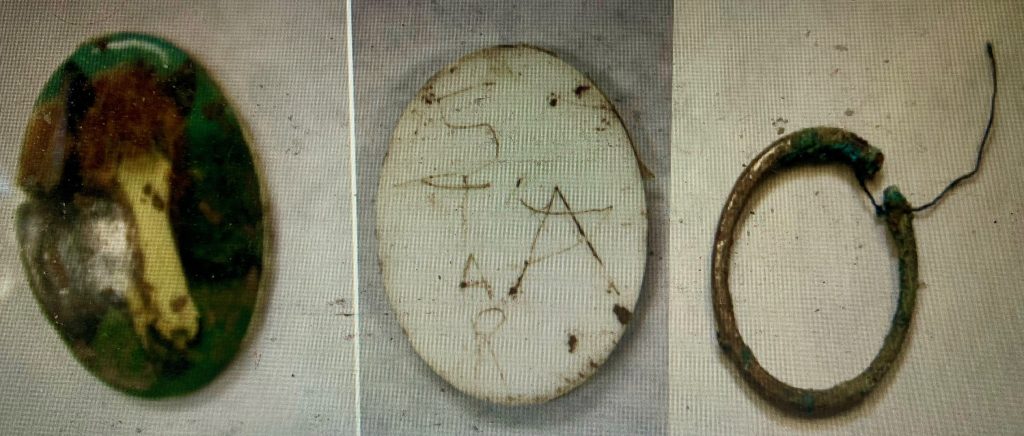

Armed with the girl’s age-range and pregnancy status, the detectives are now sharing personal items that might have belonged to her. These include a small, oval-shaped locket with the face of a horse on it; a round piece of alabaster-type jewelry with the word ‘star’ carved down its surface next to a star; a metal hoop earring; a finger ring; a white Velcro sneaker; a white slipper; and a red, flat, woven, open-toe sandal.

“These items are personal items we would have located within the remains that were in the dirt,” Davis notes. “These are personal items that could be identified by a family member or a friend that knew that person. These are not uniquely identifiable items that would have a serial number, or would be one-of-a-kind, but they’re items that – if somebody knew that person – and knew that they were missing, they might be able to realize, ‘Oh, that belonged to, say, Lisa.’”

There were more items found in the burial site, too, but Davis and Sterni have been able to match them to the other victims. The pieces of the past that remain are ones the investigators aren’t sure about.

“We’re trying to identify all the property,” Davis acknowledges. “We don’t know if it goes just to one person or not.”

Based on all known facts of the Shermantine/Herzog killing spree, anyone in possession of these items would most likely have gone missing between 1984 and 1998. The detectives understand that it’s been decades since someone might have seen their loved one wearing those items, but they don’t want hesitation or uncertainty to stop anyone from reaching out if their memory might be jogged.

“If they think they have any information, contact us – even with however little they think it is,” Sterni emphasizes. “It might be something we didn’t know and that we can use. You never know.”

While Davis and Sterni have only come to the Linde-Calaveras shadow in recent years, one person who saw its unending heartache up-close was Katie Nelson, a former crime reporter who now works for the Mountain View Police Department. Nelson was one of the main journalists to cover the ranch well excavation in real-time. Back then, she worked for the Lodi News-Sentinel, which had the nearest established newsroom to Linden. The reporter was in constant conversation with San Joaquin Sheriff’s detectives as they bore down into the ground; and after the bodies were unearthed, Nelson had a long conversation with JoAnn Hobson’s mother about having her daughter finally located. Nelson also got to know the family of one of the girls recovered from San Andreas, Cyndi Vanderheiden. The former scribe recalls Vanderheiden’s loved ones as being “incredibly gracious” to her, inviting her to attend both Cyndi’s funeral and burial, as well as opening up to her about the anguish they were going through.

“That experience was part of the reason I ended up leaving journalism,” Nelson admits, explaining that getting to know the Vanderheidens made her increasingly uncomfortable with things future Bay Area newsrooms would ask her to do around victims.

“Now that I’m in law enforcement, I talk to a lot of families whose children have died—that grief is very, very real,” she stresses. “The time that passes between, that’s nothing.”

Today, when Nelson looks back on everything that happened, she mainly thinks about how hard Cyndi Vanderheiden battled for her life in her final moments. That’s something Herzog himself recounted to investigators. Evidence from the hunting cabin also suggest that Chevy Wheeler didn’t give her last breath up easily.

“These girls were fighters,” Nelson reflects. “Wesley and Loren, yeah, they got put away for what they did; but I hope to God that these young women – their memories – are going to far surpass anything about how they were lost in this life.”

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the writer-producer for the true crime podcast ‘Trace of the Devastation,’ a series partly about the Shermantine-Herzog murders.

I graduated in ’83. This happened way too close to home. My “wonder years” were shattered by several, prolific serial killers in the mid 70s through the 80s. The Manson Murders in ’69 set things in motion, however in the northern part of the state we didn’t fear…yet. Everything has changed. Wide open fields far outside town have been swallowed by suburban sprawl. How many secrets might be well hidden under some building’s foundation or parking lot pavement? Will the lost still matter when there is no one left living to remember them?

Evie, I still look for an answer. I remember…