By Alesha Blaauw

Sacramento’s Japanese American community gathered in excitement as the “Uprooted: An American Story” exhibit was opened in the California Museum on a recent Saturday.

Museum faculty and exhibit contributors said this special exhibit embodies forgiveness, while not forgetting the impact that Japanese incarceration camps had in the region during World War II.

Marielle Tsukamoto, 85, is a former president of the Florin Japanese American Citizens League and successor of the Time of Remembrance program. Tsukamoto proudly cut the ribbon to hurry in with the crowd following behind her.

“There was really a feeling that this story isn’t a story that has been taught in schools,” says Naomi Priddy, 35, Educator Director at the California Museum. “I went to public school in California and I didn’t know about this story until I was in college… Japanese Americans were taken from my hometown and incarcerated and that’s something I just didn’t know about. We really wanted to make sure people learned [this story] as kids.”

Tetsubumi Kevin Sayama, 50, is the senior consultant at C&G Partners who designed the exhibit. Sayama wanted it to be an immersive learning experience. As soon as visitors enter, they see the early beginnings of the Japanese-American community.

Further on, products from successful Japanese-American owned businesses are displayed on the wall, surrounded by text depicting the battles they had to fight against racism and discrimination. The exhibit notes how frequently legislation was passed that hurt the community’s progress – from banning citizenship to banning immigration altogether.

The exhibit then details the destruction of Pearl Harbor. “The Japanese have bombed Pearl Harbor,” a radio speaker plays in the background.

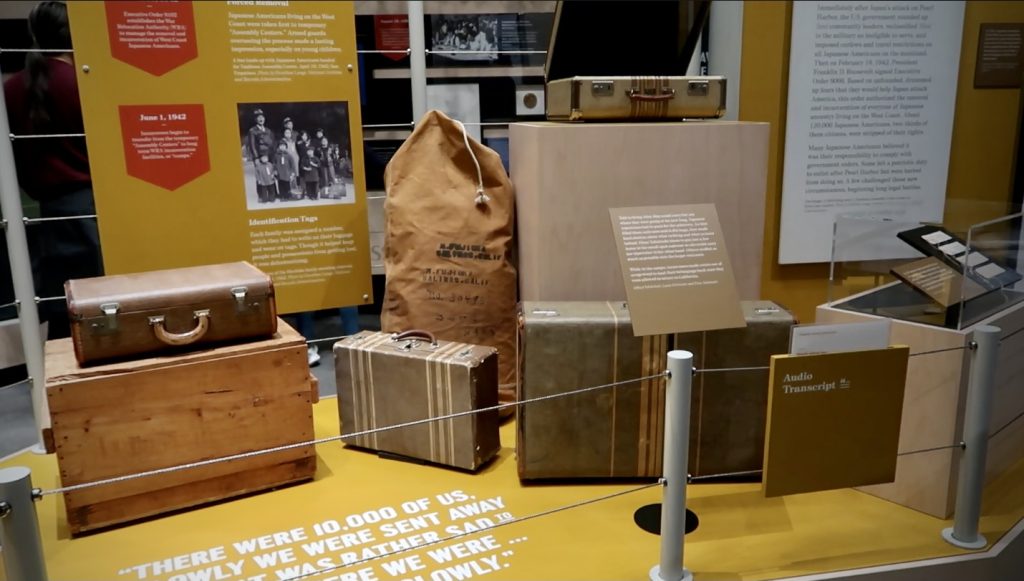

Visitors are rushed into the experience of being forced out of one’s home following the start of World War II. Luggages, briefcases, bags, crates and boxes cover the floor.

“We were told we could only take what we could carry,” a voice says in the background.

Visitors then step toward the barracks in an internment camp, a small shared space that was meant to be home for an uncertain amount of time. Incarcerees were not limited to adults – their children were brought with them.

“I was five years old,” Tsukamoto recalled. “It was cold and at night the searchlights would go across the camp, back and forth, back and forth, and there would be shadows on the wall. I would imagine they were monsters and I would cry and cry and have a hard time sleeping- even as an adult I have a hard time [with] being afraid of darkness.”

As the exhibit progresses, visitors are introduced to life in the camps, where preserved crafts, woodwork and toys are displayed. After being removed from their homes, Japanese Americans tried to make life for themselves and their children as normal as possible by taking on forms of art and encouraging play. Many others also contributed to the war effort in an attempt to prove their loyalty.

“Young men sacrificed their lives fighting in the army in the 442nd regimental combat team,” said Tsukamoto. “So many of them lost their lives, but they were trying to prove that we were Americans.”

The exhibit then shows the process of returning and repairing home. The Supreme Court ruled the incarceration unconstitutional in 1944 and families were given $25 and a one-way ticket to anywhere.

“We came back to nothing or we had nothing to come back to,” reads a quote from Kiyo Sato which is painted on the wall.

When the Japanese American people were forced out of their homes, few had supportive neighbors that would watch over their farms, businesses and property. Most families lost everything they had while they were gone for three-to-four years.

The exhibit concludes with a thousand origami cranes hanging above, symbolizing hope ahead. A letter and a check are displayed on the wall, documenting how years of fighting for recognition and redress led to the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 being passed. It granted each survivor a presidential apology and $20,000 to restart their lives.

A final message from Mary Tsukamoto is posted at the end of the exhibit in large bold letters: “Prejudice is taught. Democracy is fragile. Justice is a matter of continuing education.”

“Uprooted: An American Story” remains on display at the California Museum, which is open Tuesdays through Sundays.

Be the first to comment on "‘Uprooted’ exhibit opens in Sacramento, commemorating the darkest moment – and the tale of survival – for Californians of Japanese descent"