The memoir Life’s Work, released last fall, is a glowing testament to a writer having one last gift to give.

David Milch first made his name as a wordsmith bringing a certain level of three-dimensional humanity to what might have been an otherwise forgettable cop show called Hillstreet Blues. Milch’s work on Hillstreet in the 1980s raised eyebrows – and it led to him writing and creating a new series called NYPD Blue. What Milch did with that opportunity in the 90s was nothing less than groundbreaking at the time. The show wasn’t a black-and-white Dragnet-type rehash of badge heroics, rather it explored of the tough and messy lives of highly conflicted people operating on both sides of the law. Milch’s scripts pushed network television’s boundaries for depictions of sex, real-world dialog and acknowledging the uncomfortable traumas that we carry in the secret recesses of our existence.

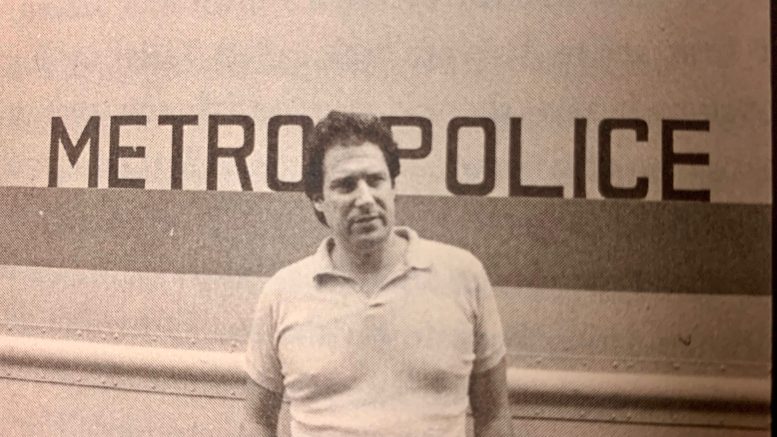

A driving force behind what Milch was accomplishing with NYPD Blue involved him becoming a collaborator with one of the best homicide detectives in New York, Bill Clark, and then mining that investigator’s career for the most haunting windows into how strangers interact with one another. Milch was unfurling what interrogation dynamics – both in our daily routines and at the police station – say about the hard corners of interior life. And his work with Clark was more of an unlikely pairing than many would have guessed. Prior to Milch’s writing career, his younger days were spent addicted to heroin and working with an acid-manufacturing ring down in Mexico. Milch reveals in Life’s Work that he saw people die below the border. He even dug a hole for the illegal burial of a man who’d succumbed to chemical poisoning. Back in the states, Milch was arrested several times.

So, like Bill Clark, Milch had seen some shit.

NYPD Blue was so pioneering that HBO recruited Milch to be part of its rising tide of narrative rule-breaking. Its executives told him the gloves of constraint would be off, and Milch responded by writing and creating one of the most uniquely mesmerizing shows to ever hit television, Deadwood. Set in a moment when the nation’s worship of gold collided with broken tribal agreements in the Black Hills of the Dakotas, Deadwood was a piercing look at the human condition when balanced between fatal lawlessness and the delicate seeds of community. Audiences had experienced nothing like it. Around round this time, Milch started telling writing students that what he strove to do on the page was “turn problems of the spirit into problems of technique.”

Like the best memoirs, Life’s Work is a revelatory peak behind the curtain of success: In Milch’s case, that means climbing to the Olympian heights of the entertainment industry while being an on-and-off-again drug addict and a hopelessly compulsive gambler. It also means telling readers how an HBO show-runner navigated his family life and lauded career with his deeply concealed pain and the reality that he was losing tens of millions of dollars at the horse track. All of this would be interesting enough, but it’s not what makes Life’s Work an exceptionally illuminating – and heartbreaking – book. After Deadwood’s three seasons were abruptly cancelled over convoluted sales rights issues, Milch typed up an even more philosophically ambitious series for HBO called John from Cincinnati. It seems to have been a creative heat-check; and it didn’t go well for him, nor his eclectic writing team, nor John’s talented cast. For a long while after that, every show Milch created was either stopped at its pilot or wasn’t green-lit in any form.

Years into his production dry spell, Miltch was diagnosed with the first stages of Alzheimer’s disease. This life-changing event coincided almost exactly with HBO announcing it wanted him to write Deadwood the movie. In Life’s Work, Milch recalls maneuvering through the slow mission-creep of dementia as he tried to have one last bout inside the artistic ring. Deadwood the movie not only made it on air, it achieved fairly universal acclaim from audiences and critics alike. To call it a creative miracle would be putting too shiny a bow on a vicious, relentless disease (and it would ignore the trusted collaborators who Milch openly acknowledges he needed to make his script come to life). But Deadwood the movie would have been Milch’s final moment in the sun if he didn’t embark on writing Life’s Work while experiencing the nearly full-throated blare of Alzheimer’s.

“I’m on a boat sailing to some island where I don’t know anybody. A boat someone is operating and we aren’t in touch.” Those are the opening lines to Life’s Work, Milch making it clear that he’s setting down his own story as his mind rages against the dying of the light.

For many, it might be an impossible proposition. Yet, using recordings that his wife made over the years of his writing process, and leveraging his family and friends’ accounts against the developing holes in his memory, Milch managed to pen a testament that’s perhaps more purely from his own writing voice than anything script that made him famous. And at the heart of what Milch is exploring is a life spent in the service of storytelling; in service of valuing the light and shadows in our core; in service of celebrating some hope for human connection. In essence, it’s a memoir about a soul dedicated to the arts. Perhaps the ultimate proof involves the fact that, even while living in a memory-care facility, Milch kept up his writing ritual every day, continuing with “the work” as he calls it. In the final chapter of Life’s Work, Milch tries to examine why that matters. As someone who chose a self-destructive path at times, only to learn that friends and family were his ultimate treasure, and as someone who experienced as many creative failures as successes, only to find he could still touch something in people with his last script, Milch was able to write book tracing the outlines of a hard world that’s full of pain, loss and disappointment, but also one that offers glimpses of something beautiful from the emotional bridges found within art.

“I choose to believe,” Milch writes. “The worthiness of getting up and reaching out, the act itself undertaken against doubt.”

*This is an opinion piece by the Editor of Sacramento News & Review. Scott Thomas Anderson is also the writer and producer of the crime documentary podcast “Trace of the Devastation,” as well as “Drinkers with Writing Problems,” a podcast about travel, culture and libations.

Be the first to comment on "Drugs, bookies, badges and gold – the frenzied horserace of a writer’s life illuminates some hope for connection"