By Casey Rafter

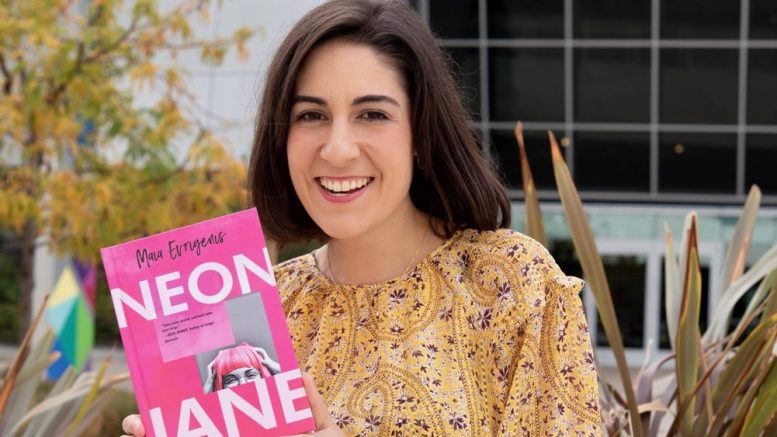

Briandi Carlile’s song “Turpentine” portrays the sorrow of lost love spurred by major life changes, while “My Body is a Cage” by Arcade Fire confesses to being tortured by social anxiety. Such musical moments, along with arraignments like Clapton’s “Tears in Heaven,” speak to grief, strife and suffering. However, there aren’t many ballads or lamentations set to music written about being 13 and facing a life-threatening illness, especially one that requires battering the body with chemicals to survive. The same is true in literature, or was until this May, when former SN&R writer Maia Evrigenis published “Neon Jane.”

The book is an autofictional look at Evrigenis’ own experiences as a teenage survivor of Leukemia.

In the novel, a 90-page journey that’s easily consumable while young patients are stuck in treatment, the author creates a second version of herself: The character Jane acts as an avatar for young Maia when she was a girl, coping with the social, emotional and physical struggles that come with preparing to enter high school while having the most-adult level situation to face. According to Evrigenis, most of the events that happen in the book are directly taken from, or inspired by, her own life.

The book’s pink cover calls out to readers, featuring the face of a girl boxed in, pushed to one side. Jane’s eyes, lined with a light colored eye-liner and squinting in frustration, seem to beckon back to the old Peanuts’ adage: ‘Good grief.’ She grabs for her scalp in frustration and touches the wig, the same pink prop Evrigenis wore herself when she endured her own treatment as a young teenager.

“Things in the book are definitely fictionalized, like auto fiction is,” Evrigenis said. “I think that’s what makes it so powerful as a form. You have this freedom to make things a little bit more magical, but … that character and the experiences — those memories are things that can come from a very true place.”

As a fourth-generation Sacramentan, Evrigenis easily employed the city as the setting for most of the book, pulling directly from sights and experiences that locals are very familiar with. When her sickness hit its peak, she was 13, going to Sutter Middle School.

Recalling when she was at her worst, Evrigenis describes being on a field of grass playing soccer and collapsing. She was just a middle school kid doing middle school kid stuff, she observed. Looking back, Evrigenis remembers not feeling well at first. That was just one day of many in the time her health spiraled toward the day of her diagnosis.

“After that, I was fine and I went back to school for like a week or so,” she recounted. “It’s these ups and downs. What really ended up happening — and I talked about in the book — I was at a sleepover; I really didn’t feel good and that launched me into this series of doctor’s appointments. My mom dropped my sister’s off — we were all at different schools at that point — I was the last one to get dropped off and she said, ‘Today, we need to go to the hospital instead.’”

The inspiration Evrigenis’ book finds has its genesis in the time she spent waiting in her first hospital bed: She hopes to show those in treatment and recovery that they’re not alone. In the four days that followed her admittance to the hospital, Evrigenis received the diagnosis of Leukemia. At the time, she had no idea that Leukemia was a form of cancer.

“I was still a kid, so they came and explained everything with little felt cancer cells,” Evrigenis said. “I think a majority of seventh graders probably understood what that was. I remember someone came in, ‘You’re gonna lose your hair,’ and I was like, ‘Oh, I have cancer.’”

Evrigenis leaned on playing the saxophone as a way to cope with her illness, a practice she started before getting sick. She even created a playlist for Large Hearted Boy’s Book Notes series, which featured songs (and notes) that she listened to while writing “Neon Jane.” Her love for jazz began as a child and she often used music as a means to adapt and deal.

“It’s this thing about me that I liked before I got sick; I was in the jazz band and saxophone was kind of a processing thing for me,” Evrigenis explained. “I found it difficult to listen to jazz while writing a book. Listening to jazz, I kind of have to focus more. Those songs helped fuel the rhythm of the book.”

After beginning the writing process of “Neon Jane,” Evrigenis reconnected with some of her original doctors and nurses at Stanford. Dr. Kara Davis was Evrigenis’ primary oncologist when she transferred from Sacramento to the young adult cancer ward at the university. She’d already had one experience with young, pink-wigged Maia as a patient. When Davis got to know Jane in Evrigenis’ novel, she was surprised to see how much of a lingering impact the experience still had on her life.

Davis holds a special place in her heart for cancer patients diagnosed at the same age Maia and Jane were, adding that they teeter on the edge of ability to understand their diagnosis and the potential impact it can have on their lives. According to Davis, patients younger than Maia can often absorb the experience with better ease, undaunted by the ghost of their childhood illness.

“This very special group of patients who are in this time where they’re really emerging from their childhood; transitioning into adulthood, but not quite there,” Davis said. “For Maia, for instance, it had been very much in her formative adolescent years and coping with that in a different way than a three-year-old or a five-year-old. I think it made such an impact on her and that was profound for me in thinking about … trying to make sense of a life-threatening disease on top of all the really hard parts of that time for any of us, normally.”

Another member of Evrigenis’ original care team at Stanford, Pam Simon, champions “Neon Jane” as an important book for patients, families, friends and supporters. With 33 years of experience as a nurse-practitioner in oncology, Simon said it’s easy to get lost in the mindset that you’re providing pediatric care and, as a nurse or doctor, not think about what a young adults’ minds do in response to such a traumatic experience.

“I read the book and immediately realized that she was talking about everything that we preach and offer in our program,” Simon pointed out. “We have pediatrics, and we have adult medicine, hospitals and institutions. Neither one of those are really focused on this age group, so what we found is that there [are] unique needs and challenges for these patients.”

Simon said that, through her writing, Evrigenis offers insight into the life of a cancer survivor from start to finish — though she acknowledges patients really don’t ever get over going through treatment. As depicted in the book, there’s often a shadow of the suffering when young patients grow to be survivors, ever-focused on making the battle worth it.

“The focus is really on [getting young patients through treatment] so sometimes, fertility, psychosocial issues, peer to peer support, education, career — all of those things get interrupted by a cancer diagnosis,” Simon said. “When you read the book, you see that it’s affected her in some ways the entire time. She needed to … process that it’s always a part of her. I see that in all of my patients.”

Now, Evrigenis is going to be a part of the hospital’s young adult cancer patient advisory council, helping to inform the decisions of care made by the teams of doctors and nurses at Stanford. That author mentioned that, after sharing her experiences in such a personal manner, this very private event has become something she no longer feels she can hold back. Sharing with those in a similar situation can only help them.

“I don’t necessarily feel super sad and ruminate on my cancer experience every day now, but I definitely think about the idea that I went through something,” Evrigenis admitted. “I think meaning and achievements feel different to me now. I think I used to feel this pressure [that] I have to be a best-selling author. I have to be this and that and I think now … Success means something different and I think surviving cancer to me … If I’ve got my health, and my friends and my family, that is so worth it. I don’t put as much pressure on myself anymore.”

Be the first to comment on "Neon Maia: A young Sacramentan’s journey from cancer diagnosis to writing success"