By Scott Thomas Anderson

The Yavapai County Sheriff’s cold case unit gathered over a scar chopped into the rocky red earth along a hill.

It was January 2017 outside Bagdad, Arizona, and the investigators – flanked by cactus, sagebrush and desert-lit views of a broad copper country – were staring into the hole that their backhoe’s bucket had been cutting six feet down. Before them was something they’d been hunting for years: It was a man’s skeleton. They could see the bones were mixed into the dirt and what remained of his hat, sweatshirt and blue jeans. The remains were fairly preserved for being hidden under sand for so long. The detectives spotted two femurs, a piece of the radius, a portion of the sacrum, fragments of the scapula and a mostly intact skull. Looking close enough, one could even make out that the man was wearing Reebok gym shoes and Faded Glory denim. And he still had his white and chrome folding knife. It was the knife of a man who loved being out in the wild – the kind of knife that would be carried by the man they’d been searching for.

Beginning to exhume the bones, the detectives found three 9mm bullets below them.

The hunt for these remains had started long before in a different mining territory in Northern California. That’s where Lawrence Powers, a member of the Gold Prospectors Association of America, had first turned up missing. As the weeks went on, a worried sister’s intuition convinced a Sheriff’s detective to launch a probe that would take on a life of its own, ultimately spanning three states, multiple law enforcement agencies and 60 changings of the seasons. Lots of footwork would be done over time by investigators from the Golden State to the Copper State; and there would be many searches of this dry, unforgiving land where members of the cold case unit now peered at their hidden treasure of evidence.

As the remains were being put into two bags, Yavapai County Sheriff’s detective John McDormett knew it would take a medical examiner and forensic anthropologist to solve the final mystery. When Powers, a 58-year-old carpenter and outdoorsman, first vanished a decade before, his prospecting partner had assured everyone that the mercurial minor was just off the grid again, probably searching for gold along the dusty banks of California’s Feather River. But the collective effort from law enforcement that began in 2007, paired with the meticulous work of bone experts, ultimately convinced a jury in March 2022 that this wasn’t a case of a rugged pathfinder who’d had an accident while seeking fortune and solace, but rather it was the oldest story of the frontier itself: Two men head into a mining claim – only one man walks out.

The sentencing for that murder story was completed last week.

The Avid Adventurer of Calaveras County

It was a searing afternoon in July 2007 when Calaveras Sheriff’s detective Josh Crabtree rolled his SUV through Murphys, California. He drove by its rust-tempered overhangs and a rock-and-brick bunker escaping the hills’ gravity for 148 years. Murphys lies at the heart of California’s Gold Country. Navigating Main Street, Crabtree passed a century-old, sunbaked hotel – another survivor from the roughneck world of the town’s early days. The hotel’s wagon wheel gate marked where the backstreets started opening on a wide, brushy expanse of oak woodlands. Crabtree was following up on a missing person’s report. He drove out into the weedy country. His SUV shook on grated cattle guards, bumping by lonely horse corrals and antique tractors littered against the manzanita and madrones. Finally, the investigator arrived at a house mostly hidden by walls of enclosing chaparral. Joan Shattuck, then 51, met him at the gate. It was her brother who had disappeared.

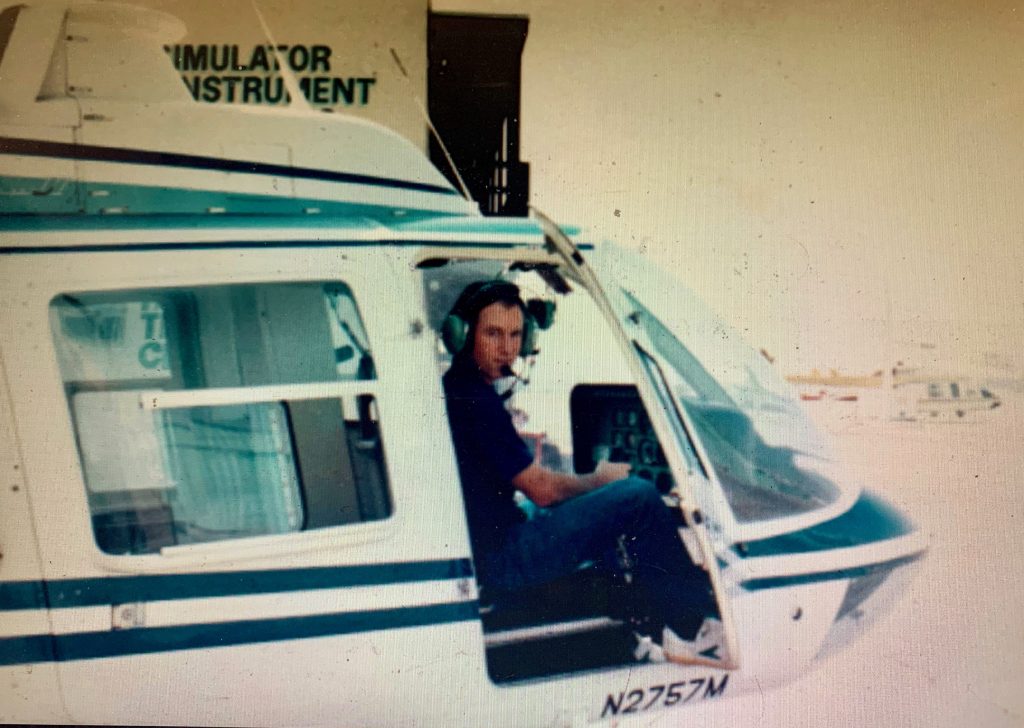

Friends say Powers had an uncontainable energy. He was a diehard skier, an experienced scuba diver, a motorcycle and dirt bike rider, a hard-charging drummer and a longtime helicopter pilot who loved gliding through the clouds. He was also a self-styled inventor. Powers lived in Murphys but also kept a mountain cabin up in Bear Valley and was building a second home in southern Calaveras. His wide circle of friends knew when he wasn’t framing walls, he might be indulging one of his newer hobbies, gold panning over the pebbles of the region’s creeks and rivers.

Powers wasn’t the first prospecting individualist to call the area home. In 1865, a young Mark Twain moved to Angels Camp and worked just eight miles south of where Powers built his house 120 years later. Twain’s vignette about the hardscrabble, highly eccentric gold addicts drinking their days away near Murphys, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” marked his first rung up the latter to literary stardom.

And before the saga of Lawrence Powers was over, one of Mark Twain’s observations would be invoked inside a courtroom 700 miles away.

Concern about Powers first started in mid-April 2007 when his neighbor noticed he hadn’t been around for some time. She phoned Shattuck, who in turn spent the next few weeks growing more and more concerned. Shattuck eventually learned that her brother had left on a gold mining expedition to Arizona with his prospecting buddy, Anthony Richards. Powers and Richards formed a bond when the latter worked as a helicopter mechanic at the Calaveras PG&E hanger. But, for a while, Richards had called Christmas Valley, Oregon, his home. Shattuck left him a voice message. When Richards called her back, he started regaling her with a long-winded tale of picking her brother up in Murphys, driving the two of them to southern Arizona, bringing Powers back to Calaveras, and then the two crisscrossing each others’ paths back to Oregon. Richards ended his account by saying he’d last seen Powers heading off with some mystery man. The pair, Richards claimed, had a plan to go back to California to try gold panning on the Feather River near Oroville.

A disturbing feeling sunk hard into Shattuck’s core.

“Everything about it was wrong,” she remembered years later. “The conversation went for three-plus hours, when I’d expected maybe a ten-minute talk. He was all over the board, and almost incoherent.”

When Crabtree arrived at Powers house that summer to follow-up, Shattuck opened the gate to let him onto the property. She’d already handed the detective one of her brother’s maps of the copper mining region of Bagdad, Arizona, which had hand-written coordinates scrawled all over it. She also gave Crabtree a trail of suspicious bank recipes from one of Powers’ credit cards. Now, as the two of them looked around the lost man’s house, they could see it was covered in spiderwebs.

“It was obvious he’d been gone,” Crabtree said much later. “It was as if somebody had lived there one day and then, suddenly, never again.”

In a nation where more than 600,000 people go missing every year it would have been easy enough for the investigator to throw this anomaly of empty space onto the round file – a low priority probe in a broke-ass county that’s rattled by meth-fueled mayhem every week.

But something about the house’s eerie silence got Crabtree’s attention. He decided to call for cadaver dogs to sniff the property. The canines didn’t find a body, but the more Crabtree examined the paper trail Powers had apparently left behind in his pursuit of gold, the more he would become convinced Murphys’ missing man had been dry-gulched somewhere on the high drifting sands of the West.

Today, Crabtree is a sergeant with the Calaveras Sheriff’s Department. When he thinks back on Powers’ story, he focuses on the nexus between missing person cases and undetected homicides. Discovering that nexus, he says, starts with paying attention to a loved one’s instincts.

“When someone tells you that something’s really wrong, you know, ‘I haven’t heard a thing from them’ – when they get to that point, that’s when cops should take it more seriously,” he observed. “Sometimes it’s just too easy to say, ‘Well, we get these every day.’”

‘Here’s where we start running into problems’

In a sense, Joan Shattuck was the first true detective trying to unravel what had happened to her brother. She’d spoken with Richards several times on the phone, recording those conversations. Meanwhile, Crabtree got a DNA sample Shattuck and entered it into the U.S. Department of Justice’s Missing Persons DNA Program. He also tracked down Powers’ dental records. Then, it was time for the investigator to call Richards himself.

In their first conversation, Richards reiterated that he’d last seen Powers in Christmas Valley, Oregon, spiriting off with an unknown man in a fifth wheel to try for nuggets on the Feather River.

“He’s my best friend, my buddy, my partner,” a worried-sounding Richards lamented through the receiver.

Crabtree began studying Powers’ credit card transactions. Powers and Richards were supposed to have been on a triangular expedition between Oregon, Arizona and California. The detective zeroed in on charges made in Utah and Wisconsin. One of them was to Rock Auto. Crabtree called the business, learning that the transaction was for a vehicle’s drive-shaft that was shipped to Oregon – where Richards lived. Crabtree also spotted a charge that was made for a computer printer in Oregon just a few days before Powers was officially reported missing. He called Richards for a second time.

The recording of how that conversation transpired was later played for a jury.

“Well, help me understand some of the charges,” Crabtree began in a steady voice. “And, this is probably the part where you’re going to think I’m an asshole, but on the 3rd he left your house; on the 4th there’s a purchase for some radio control stuff.”

“May 4th?” Richards repeated, conjuring a clip of surprise. “Really?” He paused a beat and re-set himself. “He did make a purchase through RC Boys,” Richards confirmed, “for some airplane parts.”

“Where were those going to?” Crabtree asked.

“Here,” Richards said nonchalantly.

Crabtree began to ask about another purchase, but Richards broke in with a story that Powers had owned him money, so he’d been buying Richards gifts on the credit card to repay his debt.

“But, see, he buys these after he’s gone?” Crabtree countered with some doubt.

Richards began saying that, now, he wasn’t actually sure when he’d last seen Powers.

“I’m only assuming that’s the last time I saw him,” he slightly stammered, “when I print everything out.”

Crabtree brought up more purchases. “Here’s where we start running into problems,” the detective told him.

The jury would go on to hear Richards’ tone – his answers – shifting quickly. Then, in what may have seemed out-of-nowhere to the former mechanic, Crabtree said of Powers, bluntly, “Well, I think he’s dead.”

“I hope not,” the other shot back. Mustering a show of earnestness, Richards emphasized that his good old buddy “LP” probably just went off-line and exiled himself in the wilderness for a time. Richards tried to say that Powers had a habit of doing that.

“He’ll disappear and be secluded for 6 to 8 weeks,” Richards exclaimed, “then, you can’t get rid of him.”

“Right,” Crabtree quipped, “but, still, he’s paying his bills during that time.”

Payments for Powers’ bills went dark after he was last seen with Richards.

Jurors also heard, during that conversation, Crabtree ask Powers about the supposed mystery man he claimed to have seen: “And you don’t know this guy’s name that he’s with?”

“Oh,” Richards gave a pause, “he just introduced him to me, and it was, you know, one of those things that was late in the evening before dark.”

At another point in their exchange, Richards assured Crabtree about how much he cared for Powers.

“I miss him,” Richards bemoaned. “He was my best friend; and if you were to see my phone bill, you’d see we’d spend hours on the phone.”

Hearing this, Crabtree asked what Richards thought the chances were that his pal might have said something to spur the alleged stranger to harm him. Richards replied that the chances were good. LP, he found himself admitting, rubbed a lot of people the wrong way.

“Would people call him an asshole if they just met him for the first time?” the detective asked.

“Oh, you bet!” Richards stressed.

Before the interview was over, Crabtree threw a question at Richards he didn’t seem to expect. “If I were to get rid of a body up between your house and, let’s say Oroville, where would be the best place for us to look?”

“Oh God!” Richards blurted, “you’ve got all of the Sierra Nevada, all of the Cascades.”

He added, referencing El Dorado County, “There was Gold Hill – I gave him a map to Gold Hill.”

Desert stories

“The desert tells a different story every time one ventures on it” – Robert Edison Fulton JR

Lawrence Powers never made it to Oregon with Anthony Richards.

He certainly never had a chance to go to Gold Hill.

Investigators for the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Office had determined this much.

While Richards tried to throw law enforcement attention at searching El Dorado and Shasta counties in California, Yavapai’s detectives realized that the last place Powers was actually seen alive, by other people, was within their jurisdiction in Arizona. It was on a 600-acre mining claim in the craggy, high desert copper county surrounding Bagdad. The Sheriff’s search and rescue team began combing the remote landscape for a hidden grave.

Today, Yavapai County Deputy District Attorney Ethan Wolfinger notes that this searching moved across a vast terrain of mesas, basins and tailing mounts which prior generations had been plundering since the days of the Earp Brothers’ range war on the other side of the state.

“Historically, it’s a mining district, so there are holes and depressions all over because people have gone out there for a hundred years, digging,” Wolfinger explained. “I think everybody thought that the body was somewhere in that mine; but it’s a huge amount of space, and a lot of it’s wilderness.”

Nothing came of the 2007 search.

Three years later, the search team conducted another herculean effort across the desert. Lawrence Powers stayed lost somewhere in the hot, arid openness.

In 2012, with the support of Detective Crabtree, Joan Shattuck had a court in Calaveras County officially declare her brother dead.

But sheriffs in Yavapai County didn’t give up on the case – and Shattuck was a big reason why. She had shipped them 15 cassette tapes of Richards being recorded as he told evolving versions of his story. Sometimes he’d be speaking to her. Other times he was answering questions for Powers’ friends. In 2016, Paul Chastain, a cold case unit volunteer and retired detective, began carefully listening to all of those exchanges, along with two pivotal recordings that Crabtree had made. He also had a long conversation with Shattuck about all the information she’d collected over the years. Shattuck would come to view Chastain as the true hero of her brother’s case. Chastain, who works alongside Detective John McDormett, became convinced of foul play. That year, he and McDormett flew out to Oregon to meet Richards.

“When you mapped it out, his story didn’t make a lot of sense,” Wolfinger recalled. “They confronted him in 2016, and, low and beyond, he offered a totally different set of facts.”

The detectives felt that they didn’t have enough to arrest Richards for murder, but they did have enough to hook him for a series of financial crimes. Powers’ best friend was taken into custody and transported back to Arizona, where he was locked in the Camp Verde Detention Center. Then, in January of 2017, a member of Yavapai’s search and rescue team began using an ariel drone to scan for Powers remains. Watching the footage, the team noticed a small depression that sunk down at the top of a hill. It was about a football field away from where Powers and Richards had been camping. It looked interesting to the searchers. After hiking out to see it up close, McDormett made the call to start digging. The backhoe went six feet into the earth before camping supplies started coming up in the broken soil.

And then, remains.

Forensic anthropologist Bruce Anderson determined that Powers’ right patella – a very strong bone – had been blown out by blunt force trauma. He also identified fractures along Powers’ sternum and ribs. Anderson wrote that the fractures “could have resulted from blows to the decedent’s body while alive, or from the rough-handling of the body as it was placed in the clandestine grave.”

Given that, and given the bullets found under the bones, Yavapai County Medical Examiner Mark Fischione made a determination of homicide. Fischione noted the battered ribcage could not be ruled out “as a result of gunshot wounds,” adding that, “the possibility of Mr. Powers also being buried alive cannot be entirely ruled out.”

A Twainian truth

Mark Twain, the writer who’d staked his literary claim on the very soil that Powers called home, once observed that “if you tell the truth, you don’t have to remember everything.”

That nugget of wisdom equaled a major theme in the second murder trial of Anthony Richards. The first one had ended with a mistrial in winter of 2020, after a potential witness in the case communicated with one of the jurors. After that, the case was handed to Wolfinger, a 30-year veteran prosecutor in Yavapai County. The legal journeyman was told to prepare for a new showdown in the early spring of 2022. Wolfinger began pouring over the evidence.

“Six weeks before the second trial was the first time that I heard the name Anthony Richards and got the case file,” Wolfinger remembered. “What was critical was that no one knew how it went down with the defendant and victim, or how the victim died. Obviously, something happened on that campsite when the two of them were there, alone, out in the middle of nowhere; and whatever it was led to the victim’s body ending up in a mining hole.”

Wolfinger called a series of witnesses to the stand, including having Crabtree fly in from California, to debunk Richards’ claims that Powers went galivanting off with some sketchy stranger in the night.

“When he talked to Josh Crabtree on the phone, he gave a totally different description of this third-party mystery man that he had to other people,” Wolfinger explained. “It went from a clean-cut guy, no beard, buffed-up, to suddenly, a biker dude.”

The prosecutor added that this was one of countless inconsistencies from Richards that caused him to invoke Twain’s mantra about tracking one’s own lies.

“He couldn’t remember, on details, what he’d said before,” Wolfinger noted of Richards, “because he’s a bull-shitter. So, he’d always talk, but then he’d give some other story. Honestly, I don’t think I’ve ever had a case where a defendant has been talked to by so many people, so many times – willingly talked to – and then couldn’t remember what he’d said, so just kept coming up with something new and different. His lies really, really nailed him.”

At the start of the trial, Richards’ attorney told Wolfinger that his client planned to testify. However, after watching Shattuck, Chastain, McDormett, Crabtree and others testify, the accused man changed his mind.

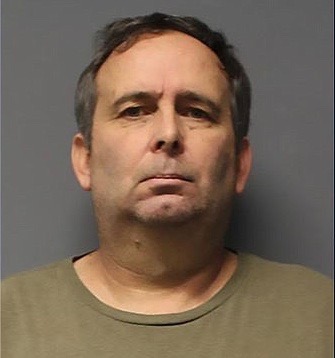

On March 3, 2022, the jury found Richards guilty of 2nd degree murder and 23 financial crimes related to identity theft, forgery, credit card fraud and trafficking in stolen items. Last week, Richards was sentenced to 30 years in state prison.

“For everything to happen the way that it did, I believe God was in the story the whole time, because there were more than a few miracles that took place,” Shattuck told SN&R after the verdict. “They were genuine miracles, and that’s what I take from this.”

For Crabtree, the case taught him about the often-dark phenomenon of missing persons.

“When I first met Joan, you could tell her brother was very important to her and a significant piece of her life, and then he’d just vanished,” he recalled. “And there’s a lot of people that go through that. What I didn’t quite realize, until I got this case, was just how many people go missing. It’s hundreds of thousands every year. And you wonder, ‘How do they just vanish?’”

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the writer and producer of the true crime podcast series “Trace of the Devastation,” which is about a series of crimes in Calaveras County, California.

Wow! Great story, Scott, with clearly your good, in-depth reporting and major drama. Love your line, “And then, remains.” Fascinating read.

Scott, great thx for your ultra well written story of Larry Powers death and the long awaited conviction of his murderer. I feel your article will help close this awful chapter for Ms Shattuck, knowing that her brother’s story has been truefully told .

Thank you again,

Pete Mc

Scott,

Congratulations on a riveting account of amazing detective work! Joan Shattuck’s tenacity and the Cold Case Team’s doggedness solved a mystery that covered so many years and such a vast area that one would think a solution would be impossible.