Special agent Martin Ryan could hear the tiny plane’s engine droning against the clouds. Far below the jet stream was the lush tree cover of Saskatchewan — and seated a few away from the agent, was one of the deadliest serial killers in California’s history. Ryan was staring at Charles Ng, the man who had helped kidnap and kill more than 17 men, women and children, including babies. Ng was hunched in a dark moss-colored jumpsuit. His wrists were bound. His ankles were zipped in steel braces. Ryan looked down at a silver chain running between the cuffs that kept Ng’s legs shackled: Listening to the labored hum of the plane engine, Ryan suddenly put his foot down on the chain, pinning it to the floor.

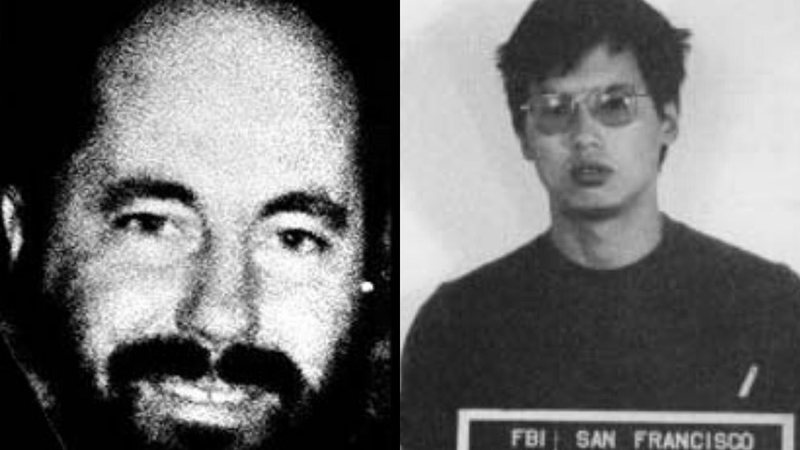

The flight marked the end of a nightmare that started six years before in a parking lot in South San Francisco. It was June of 1985 and police were answering a random theft call outside a lumberyard. Pulling up, they encountered Leonard Lake. He’d been waiting in a car while his friend – an unknown man at that moment – tried to steal a vice from inside the lumber store. The friend had been able to vanish on-foot into the surrounding neighborhood. Lake was still at their car. A longtime cop might have sensed Lake was the most chilling kind of narcissist; and he was in possession of a missing man’s identification, a different missing man’s car, and a gun fixed with an illegal silencer.

Officers brought Lake to San Francisco police headquarters for questioning. He was only there for a brief spell before foam started pouring out of his mouth.

Leonard Lake had swallowed a cyanide capsule.

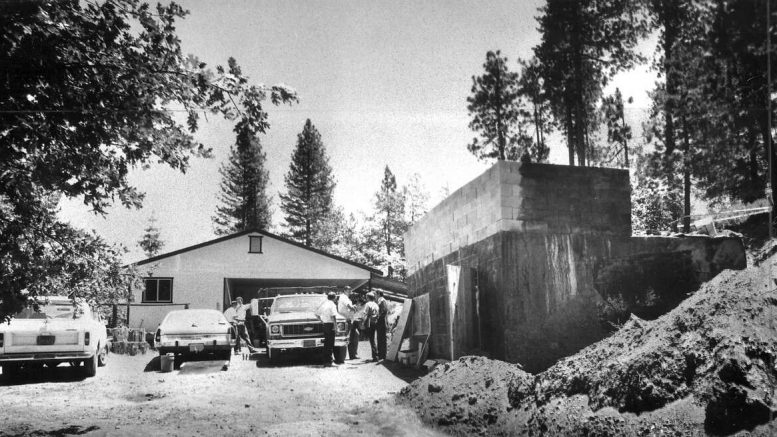

San Francisco police soon followed their dead suspect’s identity 150 miles east to a foothill backwater called Wilseyville. They breached Lake’s isolated property on Blue Mountain Road with some Calaveras County Sheriff’s detectives by their side.

Meanwhile, special agent Ryan was slowly settling back into life in the Gold Country. Ryan was the son of an Amador County superior court judge and the grandson of a legendary Amador County Sheriff. The D.O.J. agent had recently been transferred from an assignment in southern California to the agency’s headquarters in Sacramento.

“I remember being in the office and hearing a call come out for seven or eight body bags in Calaveras County,” Ryan recalls. “I was living in Jackson at the time, and I had no idea what a huge undertaking I was about to get involved with.”

The Department of Justice sent Ryan and other state agents up to Wilseyville. Their mobile crime lab was soon processing the human remains being pulled from ditch lines along the mountain’s rocky woods and walls of Manzanita. The mind-numbing forensic work began to indicate that the Blue Mountain address was the site of a mass burial.

Leonard Lake’s diary, along with a series of homemade videos that he and Charles Ng made of their victims, constituted an unmatched, uniquely Californian horror story: Lake and Ng had been kidnapping men, women and children for at least two years, holding most prisoner in a bunker, raping the women, and then slaying everyone in a de facto torture chamber.

Ryan and a brigade of detectives from San Francisco and Calaveras were confronted with unraveling the mystery of the victims’ identities, as well as how each of them came to be ensnared in this remote place of no return.

“Hundreds of people had to be interviewed in different parts of the state,” Ryan remembers. “We had to trace all of the various relationships that connected the victims to Lake and Ng. I think what ended up making the case so striking, and so challenging, was how diverse their victims really were. They came from all walks of life. They ranged from prostitutes to a used car salesman, to a member of the Guardian Angels, to a middle-class family that ran a videotaping business. There wasn’t really a common threat, other than killing for Lake’s financial gain, and his fantasies — and picking victims according to what opportunities fell in front of them.”

More than anything, the investigator needed to know where the hell was Charles Ng?

Nearly one year to the day that Leonard Lake swallowed his cyanide, Ng was arrested in Alberta, Canada, after he shot a security guard during a botched shoplifting spree. Knowing that Ng was in chains was limited comfort to the detectives who were chasing him: The Canadian government had a strict policy about not extraditing criminals to the U.S. if those suspects were facing the death penalty.

Ryan was named Chief of the Department of Justice Task Force on the Leonard Lake and Charles Ng homicides. His main task was linking the chain of events that had brought each murder victim to their final moments in Wilseyville. Ryan’s team eventually brought 17 cases to the Canadian High Court in 1988. The court only recognized 12 of these murder counts as potential grounds for extradition. Twelve was a hard number for the detectives to swallow, but they’d have to live with it. They had to get Charles Ng into their custody. None of the investigators could forget the deck of victim-Polaroids he’d left them. Nor could they stop thinking about the two smiling infants that were lost.

In 1989, Ryan and the U.S. Marshals flew to Saskatchewan to get their hands-on Charles Ng. It was about to become one disappointing trip. After arriving, Ryan learned that a Canadian Minister of Justice ruled Ng could only be extradited to California if authorities promised not to charge him in a way that would lead capital punishment. The Americans went home empty-handed.

Not all Canadians were thrilled to be holding a man like Ng on a four-year prison sentence within their borders — a sentence that he could potentially be released from. A growing unrest began to smolder up North, debate raging about whether Canada would become a new haven for serial killers fleeing the U.S.

In 1991, the Canadian Supreme Court decided to turn Ng over.

Ryan and several U.S. Marshals loaded onto a small plane bound for Saskatchewan. Its wheels touched down on September 26, 1991, and Ryan’s team headed straight for the prison. Though flanked by supportive Canadian Mounties, Ryan was still haunted by the thought that his mission might fall apart at any moment.

“We didn’t know if there was going to be a last-minute legal appeal,” he says. “We’d already been there before, and we’d had it shut down on us. We were worried it would happen again.”

The prison warden soon handed Ryan a certificate that declared he’d been temporarily “appointed and commissioned as an honorary inmate of Saskatchewan Penitentiary” in order to operate on the facility’s grounds. Once the marshals brought Ng outside, Ryan’s team hustled him into the plane and shut the door. And then Ryan sat across from the killer he’d been hunting for over half-a-decade. The agent knew that guards inside the prison had confiscated drawings from Ng, ones that portrayed specific sexual torture he’d engaged in with female victims, as well as his new fantasies about killing a number of San Francisco police detectives who’d worked his case. The drawings made it clear that Ng dreamed of getting even with the men who’d been pursuing him.

Staring at Ng over the loud, sputtering engine, Ryan dropped his foot down on the chain between the killer’s ankles. Ng never spoke a word. As the plane left Canadian airspace, Ryan realized that his part of the chase was coming to an end.

“I don’t think I actually felt a sense of closure until years later, when the trial ended,” Ryan admits. “It was probably during his sentencing, when family members of all of his victims finally had the opportunity to speak for themselves, and tell the court about how his crimes had affected them.”

Ng was sentenced to death. He is currently imprisoned on death row at San Quentin.

Martin Ryan went on to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps by becoming Sheriff of Amador County. He held that position with distinction for 15 years, retiring in April of 2021.

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the writer-producer of the true crime podcast ‘Trace of the Devastation,’ which is partly about the Lake-Ng murders.

Be the first to comment on "The Long Flight Home: revisiting how detectives finally grabbed one of the Capital Region’s worst serial killers"