The potential remedies for the state’s drought-related problems are diverse, complicated and divisive

By Steve Appleford, Capital & Main

This story is produced by the award-winning journalism nonprofit Capital & Main and co-published here with permission.

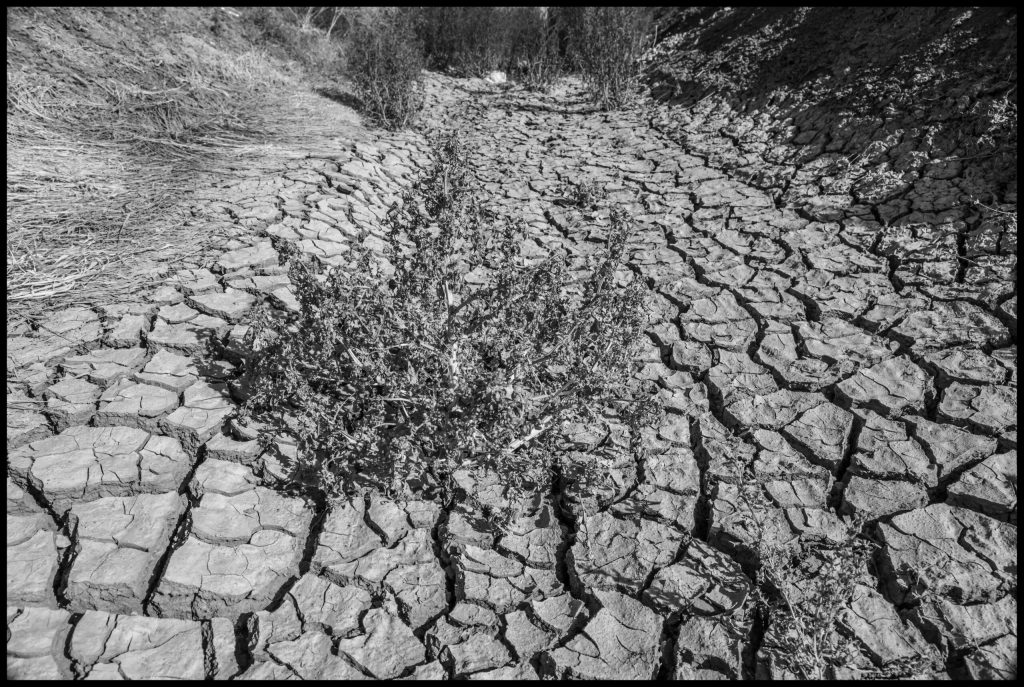

In California, there will always be droughts. And even in good years, there will never be quite enough water to satisfy the demands of the state’s urban population, its natural environment and an insatiable $50 billion agriculture industry. Climate change has only made the problems worse.

In 2017, Gov. Jerry Brown declared that the state’s last devastating drought was finally over, following a heavy rain season that replenished reservoirs and the crucial snowpack of the Sierra Nevada mountains. “But the next drought could be around the corner,” Brown warned then. “Conservation must remain a way of life.”

Four years later, that prediction has come true even faster than many expected, with few clear solutions. California now faces increasingly warmer temperatures and an unreliable water supply. This year, wildfires have destroyed more than 2 million acres, and some towns have seen their wells go almost completely dry.

“It’s obviously a big, big problem. And magic solutions are hard to come by,” says Glen MacDonald, a water expert who holds the endowed chair in geography of California and the American West at UCLA.

The potential remedies for the state’s many drought-related problems come from all directions and are far more complicated than simply throwing money at major capital investment. As beneficial as new water infrastructure would be (while also creating thousands of new jobs), water experts say it must be part of a larger effort that includes better management of existing water supply, with rainwater harvesting, recycled water and changes to outdoor landscaping and farming.

“This is something that is going to require multiple approaches,” MacDonald adds. “Some smaller scale, some larger scale.”

Roughly 80% of the state’s water goes to agriculture, and 20% to the population.

“California has droughts, just like the East Coast has hurricanes and the Midwest has tornadoes,” says Jay Lund, professor of civil and environmental engineering at UC Davis and co-director of the university’s Center for Watershed Sciences. “California has the most variable hydrology of any part of the country. We have more drought years and flood years per average year than any other state.”

Last year, the BlueGreen Alliance called for investing $105 billion in U.S. water infrastructure over 10 years. The group noted that American cities are still served by pipes that are, on average, about a century old, and leak 6 billion gallons of clean drinking water daily.

“In Southern California especially, you have many miles of pipelines that are leaking and they’re in urban water areas,” says Brandon Dawson, director of Sierra Club California. “How are you fixing those and allowing for more water to pass through the system?”

Aside from drought relief, there is obvious economic benefit to new investment. For every $1 billion spent on water infrastructure, 30,000 new jobs are created in plumbing, pipefitting and other work, according to the nonprofit advocacy group Clean Water & Jobs for California. In 2017, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave U.S. drinking water a grade of “D/D+,” suggesting an urgency in terms of public health that even goes beyond water shortage and job creation.

The bipartisan infrastructure bill recently passed by the U.S. Senate (and still awaiting action in the House) includes funds for water storage, water recycling and desalination. The bill provides $8.3 billion for Western water infrastructure and $55 billion in what the White House calls the largest ever investment in clean drinking water in U.S. history.

The worst of the crisis is being felt in California and the Southwest, but a look at the drought monitor at the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln shows the problem only growing with the effects of climate change. The map shows the drought extending across the Western half of the United States, putting more pressure on water sources shared across several other states, from Nevada and Arizona to Montana and Washington.

“Next time it will be all the way to the Midwest,” says Samuel Sandoval Solis, an expert in water resources planning and management at the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences. “Would more investment help? Yes, it will help. But the investment is not the solution. We have to cut it back.”

In the last drought, Californians showed a willingness to adjust personal behavior and water usage in meaningful ways, embracing low-flow showers and toilets, watering lawns less frequently and more. It’s at least partly through these conservation efforts that total urban water usage in the state has fallen despite a rising population.

At the same time, even when the larger agricultural entities of the Central Valley embrace new technologies that use less water, it’s often followed by turning the same land over to hugely profitable “water-demanding crops” like almond trees, explains Sandoval Solis.

“This is not about bringing more water. If we bring more water, rest assured that water will be used,” says Sandoval Solis. “It’s about how can we use less water.”

Environmentalists have found allies among certain farming organizations that promote water conservation and sustainability, but those tend to be smaller family farms that “understand the need to evolve,” says the Sierra Club’s Dawson. “The larger entities are the ones that we have issues with.”

Those farms can be found in the Central Valley, the Joaquin Valley and near Fresno. Elected officials have been slow to push these big farms to address their water usage at a time of shortage, says Dawson.

“There is a real concern that people should have around how California is going to be viewed if we can’t even keep water in our own ecosystems,” Dawson adds. “A lot of the endemic species that are special to California are dying off and becoming extinct because of overallocation to certain industries.”

* * *

Earlier this year on the Pacific Coast, Fort Bragg’s City Council voted to purchase a small ocean desalination plant. In the current drought, the town has seen its water supply disappear along with the flow of the Noyo River, which has fallen to levels below that of 1977, the previous worst drought year on record. The new plant would produce 288,000 gallons a day for a population of about 7,300.

While other desalination plants may be built in the state, it’s not seen as a practical solution for much of California for cost reasons alone. The desalination of seawater requires a lot of energy and produces brine, both environmental concerns.

“You could build desalination plants up and down the coast and the cities would never ever see another drought, but it wouldn’t be reasonable because it would be tremendously expensive. It would be like building freeways so large that you never had traffic jams,” says Lund. “Water conservation in most parts of the state is likely to be cheaper than desalination.”

Over the last 30 years, Southern California spent heavily on reservoirs and long-term planning, while smaller communities on the Northern California coast depend on groundwater and local wells, leaving themselves vulnerable during recurring droughts.

In some communities in Northern California, water trucked into town can cost up to 45 cents a gallon, compared to less than a penny a gallon charged by utilities in less stressed parts of the state. Meanwhile, during the current drought, leaders in the small town of Teviston, near Fresno in the San Joaquin Valley, have resorted to providing bottled water to residents.

Reservoirs serving small towns in Northern California are far below 50% capacity. The dam at Lake Oroville is so depleted that it stopped producing electricity — another costly byproduct of the drought and climate change.

“That means we’re going to be seeing more of these kinds of episodes and probably more severe than what we’ve seen in the past droughts,” says Lund. “I think we need to be prepared for it to be worse.”

The stakes couldn’t be higher for the environment, as competing interests take more and more fresh water out of the ecosystem. As the largest farming companies continue to demand the largest share of the state’s water, draining its rivers and groundwater, the real threat to fish and other wildlife grows increasingly dire.

“People eventually are going to be forced to reckon with how important these issues are,” says Jacob Morrison, a filmmaker who grew up in Southern California. His upcoming documentary, River’s End: California’s Latest Water War, examines the state’s water issues. “I think everyone would like to live in a California that has rivers that flow, and that has fish, that has birds. All of that relies on not taking all of the water out of our rivers.

“Ultimately, in order to solve this problem, we’re going to have to take some agricultural land out of production.”

The issues are predictably contentious. During one interview in River’s End, a young family farmer stands beside a pump on his land and says, “My grandfather told me, ‘There may come a day, son, when you’ll have to sit on that pump with a shotgun.’”

The future of water in California may appear grim, but UCLA’s MacDonald takes some encouragement from the state’s response to an earlier environmental crisis, pointing to the out-of-control air quality challenges that created a ghastly layer of smog over Los Angeles and other metro areas, much worse than today. By the end of the 1960s, the Hollywood Hills were often shrouded under a blanket of smog.

“California’s air quality got worse and worse and worse. It was unbelievable,” MacDonald says, noting that the state instituted several measures to cut back on air pollution that proved effective. “Those eventually influenced the nation and the world, so the effect of California’s fight against air pollution was magnified. It was like ripples in a pond.”

On water issues amid the accelerating climate change crisis, California could lead the way again. “It can provide leadership, it can provide technologies and strategies,” he says, “which will then have a bigger impact on anything that happens.”

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

Fewer people and fewer farms will be in California future unless the supply of water is increased through reusing, desalination or improve water infrastructure. Whether we like the cost or not we will need some desalination plants. Israel has built them in order to survive and so will we.