By Douglas Cazaux Sackman

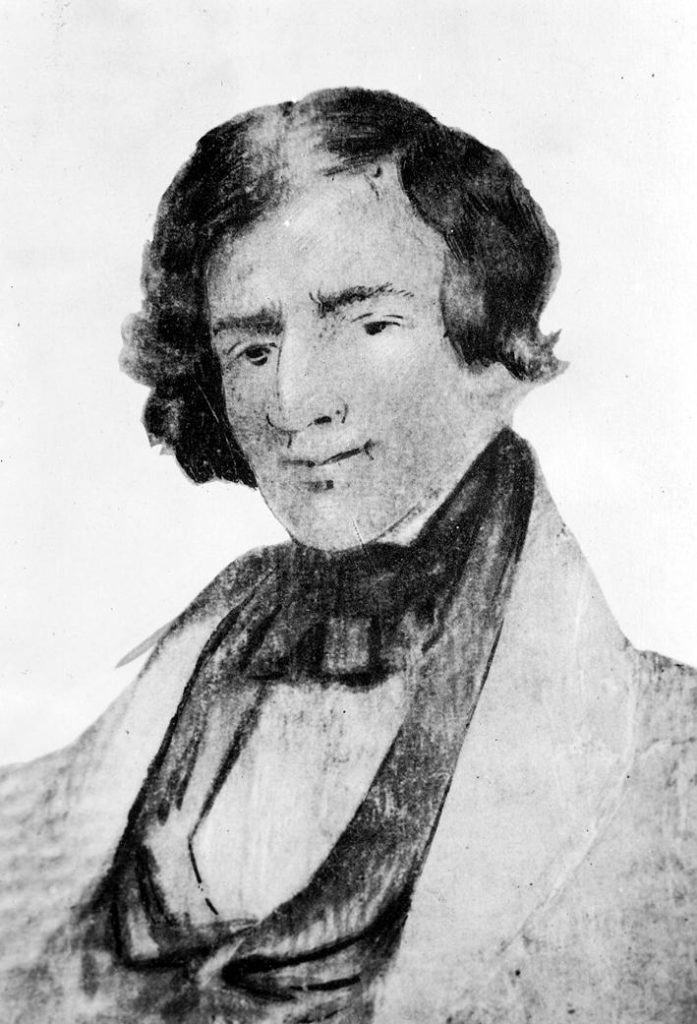

Jedediah Strong Smith met his end 190 years ago. He had used up 9 lives in his brief time on this earth, and taken many more.

A celebrated Mountain Man, he has been turned into a legend, with his name inscribed on landscapes he plundered in California and across the West in mad-dash efforts to accumulate beavers and territorial knowledge and claims.

In 1826, his fur trapping and trading brigade pushed their way from the Great Salt Lake, through Mojave territory, and into Southern California. Apprehended by Mexican authorities at Mission San Gabriel and questioned by Governor José María Echeandía, who wondered in the map-making intruder could be a spy, Smith was ultimately allowed to back-track out of California.

But the illegal alien only pretended to do so, and instead turned north, plunging into the Central Valley, proceeding to trap and trade for beavers in the homelands Native Californians that were beyond the reach of Mexican control. While plotting his way out over the Sierras, a group of Maidus stood in his way. Smith ordered his best marksmen to shoot them from afar—two fell dead. Another day, he repeated the attack on the people whose lands he was trespassing, and this time “more guns were fired and more Indians were killed.” Peaceful trade was always Smith’s Plan A, but whenever he got himself into trouble Plan B was cold lead.

Mid-way up the slopes of the Sierras above the American River, after he had driven six horses to their deaths in the heavy snow, he turned back. As if to compensate for being forced to retreat, to the highest peak he could see he had “the vanity to attach my name” (though the name didn’t stick). He left most of his brigade in California, and then tried a second time to get over the Sierras with a small group. They succeeded, and barely made it across the arid Great Basin, with help from Paiutes who he denigrated as lower forms of humanity, to that year’s fur trade rendezvous at Bear Lake on the border of Utah and Idaho.

He then went back to California to pick up his crew, was arrested again, and brought back before a very nonplussed Governor Echeandía. But Smith, complaining that “this man was placed in power to perplex me,” lied his way out to freedom. He immediately broke his promise to leave by the agreed-upon route, and went back to trapping in the Central Valley, including along the American River.

One day the brigade galloped into the Nisenan village at the confluence of the American and Sacramento Rivers, frightening everyone. Malissa Tayaba, Vice-chair of the Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians, believes this was the village of Pusane, where her grandmother was born. Most of the Nisenans ran to the river, diving in or pushing off in rafts. Smith overtook one woman, who shook with fear as she faced him, while a young girl ran away as fast as she could, but she fell and died.

Smith expressed a kind of regret, but took no real responsibility for his actions. Instead of realizing that a group with their reputation for shooting other Native Californians galloping into their homes would cause terror, he surmised that it was his Christian identity that shocked and awed her to death, attributing it to the girl being so very “wild.” So he re-christened the waterway the “Wild River,” and called out for missionaries to come among the people he described as constituting the “lowest intermediate link between man and the Brute creation.”

The Nisenan people have called the river Kum Sayo, or “roundhouse river”—connecting the river to their homes along its bank. The river wasn’t wild; it was a homeland tended and honored for hundreds of generations, and Smith ran roughshod right through it. Smith’s name for the river also didn’t stick, but it turns out that it’s probably his brief and brash beaver trapping and home wrecking the Californios had in mind when they started calling it Río de los Americanos. Doing so also ran roughshod over the Nisenans’ reciprocal connection with the river stretching back from the present to the deep past. Vice-chair Tayaba, who also directs her tribe’s department of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, explains that “we have a relationship to the waterways of this region, a relationship with the land, the birds, the fish and all it has provided and what it still offers.”

Smith’s brigade trapped beavers and hunted grizzlies as they made their way up the Sacramento Valley to the Redding area—probably the first Americans to interact with Ishi’s people—then turned northwest over the mountains to the coast. They killed several more people. They went through Hupa lands among others, begging and trading for food. In 1971, Mahlon Marshall shared what he heard about the intruders from his grandfather. When Smith’s ragged crew came into their town in the Hoopa Valley, the Hupas hid babies in baskets, traded manzanita flour for blue beads, and were shocked when the strangers ate their dogs.

Smith’s brigade exited California and blustered their way up the Oregon Coast to the lower Umpqua River, where they inflicted a variety of injuries and insults onto the Quuiich people. They abducted and put a rope around the neck of a leader who they accused of taking an axe, but it turned up buried in the sand. Smith’s men may have attempted a rape. In retaliation, 15 members of Smith’s party were killed, but Smith and 3 others survived, to straggle up through Oregon with the help of Tillamook people to Fort Vancouver operated by the British Hudson’s Bay Company on the Columbia River.

Though the American traders were rivals, the HBC treated them hospitably. They even sent out a brigade to retrieve the furs Smith had lost, reasoning that the “honor of the whites” was at stake. Nonetheless, they basically found that Smith had it coming to him. After being patched up and paid for the furs at Fort Vancouver, Smith left and then wrote a letter to the War Department and President Andrew Jackson urging the U.S. to kick the HBC out of Oregon Country (which by treaty was jointly occupied by the US and Britain at the time).

Smith then got out of the business—using his beaver profits to buy a big house in St. Louis, buy two enslaved people, and started to write a book about his travels with himself as the hero. But he couldn’t stay out of it for long. In May of 1831, he lead a caravan going from St. Louis to Santa Fe (which was still in Mexico at the time), but they ran out of water in Kansas. Smith went out ahead on his own to find some, and was never seen again (the presumption being that he was killed by Comanches).

After being nearly forgotten, Smith was born-again in the 20th century as a “Bible-toting” pathfinder and Anglo-Saxon advance man on the ground manifesting American destiny. Sacramento eugenicist Charles Goethe was smitten with Smith, and he decided he’d make Smith place-names stick. He arranged to have a redwood grove named after him as a State Park, several plaques and monuments erected, and a multipurpose trail along the American River named after him (his bequest in his will conditioned money for trail development on commemorating Smith). I can see why Goethe, who in 1936 defended Nazi Germany’s “honest yearnings for a better population” and fulminated against Mexican immigration, would want to see Smith as California’s founding father: he helped him express his racist vision for the Golden State.

I grew up riding my bike on the Jedediah Smith Memorial Trail—12 miles down from the Nimbus Fish Hatchery entrance I came to Goethe Park, a frequent destination, and in another 10 I’d pass the unmarked spot where Smith terrified to death the Nisenan girl. Growing up, I only had a vague sense of who Smith was, associating him with mountains, grizzlies, and exploration. I thought it odd that a local park was named after the German writer.

I think now of the violence inflicted on Indigenous people in California and the West by Smith and his ilk, and how his name laid down on the trail erases their experiences and their deep and continuing histories of stewardship here. I think of the way Goethe’s work helped anchored Smith here into the geography in order to make a point about “manifest destiny.” To think back now on how I obliviously and happily road along with Smith is troubling.

The mountain man enjoyed his 9 lives, and then was given a rebirth as apotheosis in the 20th century when he was memorialized as an American hero—with no mentions of the trespasses, the killings, the slave-owning, the racism, the fundamental recklessness of his avaricious actions that endangered the lives of all others around him.

The hole mountain men fur trappers would dig to store beaver pelts before taking them to market was called a cache, and they would take care to conceal it from discovery. Goethe Park has been renamed, thankfully. In my view it’s time to also say good-riddance to Jedediah, put the Smith place-names to rest, and roll up all of the hagiographic historical markers scattered across California and the West and place them in a cache to the unknown trapper.

Douglas Sackman is a professor of history at the University of Puget Sound, and the author of “Wild Men: Ishi and Kroeber in the Wilderness of Modern America.”

Thanks for Jedediah article. 6/18/21

This is why I subscribe.

Read this from Las Cruces, New Mexico