By Holly Calderone

If we ever needed more proof of Oscar Wilde’s adage, “Life imitates art far more than art imitates life,” it would be Parrotheads. My Uncle Paul died a couple days before Jimmy Buffett and it is a toss-up who the family is mourning more. Growing-up on Morro Bay in the 1970s, our grown-ups were drifting: Mom fresh off her first marriage to a biker, moving home, three kids deep. Her brother back from the Navy several years, staying out of trouble, but still perpetually hungover. Their baby sister looking for her happily-ever-after with a local surf bum. Seems nothing captured their feeling of having been thrown into the world like when they first dropped Jimmy Buffett onto the turntable.

And, as Jimmy Buffett the songwriter figured it out, so did a whole generation alongside him. Because he and all the folks who inhabit his songs of the seventies are up against it. Every existential dilemma is represented in his inimitable tropical rock stylings. So many of Buffett’s early tunes are explicitly about the human search for identity and belonging, freedom and responsibility, the universal hardships of aging and death, regret and grief. This, from a man whose name mostly brings to mind rowdy white Baby Boomers partying in Hawaiian print shirts.

Truth is “He Went to Paris” is as poignant a portrait of a man’s hard life well-lived as any Hemingway novel and there is no irony in my Gen X appreciation of Buffett as a person and a storyteller. For starters, Jimmy Buffett could write women, unlike Ernest Hemingway. He penned some heady songs about women’s struggle for self-actualization at the height of Second Wave feminism. One of his signature tracks from 1979 acknowledges one of the added difficulties of the heroine’s journey. There is not a as much space for self-reflection in the midst of others who treat you like prey, “You got fins to the left, fins to the right. And you’re the only girl in town.”

Jimmy Buffett also memorably crooned a tune addressing the phenomenon of older women being treated as worthless and how this can affect the trajectory of even a bold woman’s life. In addition to being a great train song, “Railroad Lady” is the rare song of a woman pursuing a lifetime of adventure and ruthlessly insisting on her autonomy, “Once a high-balling loner, thought he could own her. He bought her a fur coat, and a big diamond ring. But she hocked them for cold cash, left town on the Wabash.” I sang these lyrics with gusto, busting out of rural California, just turned18-years-old. Not on a train, but on a motorcycle and heading to – where, else? – Key West. Living your life like a song, indeed.

Most iconic are the lyrics Buffett wrote for a failed-debutante hitchhiker on his 1974 album Living and Dying in 3/4 Time, “Momma I’m fine, if you happen to wonder. I don’t have much money, but I still get around. I haven’t made church in near thirty-six Sundays. So, fuck all those West Nashville grand ballroom gowns.”

Sounds to me like Jimmy Buffett was pretty iffy whether he would live very long, even in his twenties and I can dig it. In the lyrics of 1974’s “Migration,” he literally muses what he will do if he lives to be an old man. He will sail down to Martinique, natch. Buffett recognizes harder task before him, though, that is seeking and finding purpose in his young life. So, when he sings, “Whoa but we’re doin’ fine, we can travel and rhyme. I know we been doin’ our part,” it is not just as some kind of good time guy, but a regret-filled divorcee seeking wisdom on how he can live better going forward.

And he got it right. I mean, Jimmy Buffett made his real fortune in the hospitality industry and diversified with some solid books. Still, from the 1980’s to 2023, he mostly recorded feel good anthems and toured constantly. Dude made his money, but was still in it for the joy. If you have any doubt, he spells in out on the track “Makin’ Music for Money” and that song is a bop. Pretty sure this mellow anarchism is what resonates with our aging hippy parents. Some Boomers became yuppies. Just as many continued to push back on the grim hustle of Late Capitalism.

Buffett also shares being baffled as to why some people seem content with discontent. He does not propose we can all be musical stars, just that we can pursue some of the many nice things happening out there. The answer, of course, is that acknowledging the degree of freedom we do have scares the hell out of us. And Jimmy Buffet’s seventies albums are rife with stories of living with the consequences of your own and others’ hard life choices. Some of the tunes are absurdly funny, like the “Peanut Butter Conspiracy” poking fun at the brokeness of trying to make it as a musician or the protagonists of “The Great Filling Station Hold-Up” ending up in the pokey. Other times, Buffett sings with heart-wrenching appreciation of the pain living one’s dreams can cause others, as he does in “Livingston’s Gone to Texas.

Still, he never proposes that people should not do the thing they think will bring them the greatest satisfaction. Is this excessively individualistic? Yeah. Pretty sure I can blame Jimmy Buffett for Mom and my step-dad abandoning the homestead just as soon as the last of us kids left, sailing off into the Pacific on a gaff-rigged cutter before any of us had cellphones. But his existentialist stance on living has fundamentally shaped our family’s way of being-in-the-world for the better. Me and my brother, our sister and our cousins, we all grew up wondering what we wanted to do with our lives and less so wondering if we were capable of it. And this passionate sense of possibility has been passed down to subsequent generations, as well.

Perhaps most of all, my Mom’s brother embodies the Jimmy Buffett’s ethos. He sobered-up with the love of a good woman and has led a life incorporating the Buffett trifecta: boats, planes, islands. Now grown-ups together, we hang out and drink our single beers, trade stories and try to make meaning of the life and family we share. Sometimes the soundtrack is A1A and the man singing “The Stories We Could Tell” is on board with eternal recurrence or I do not know what is what. If Jimmy Buffett had it to do all over again, he would most assuredly live his life just the same way he did this time around, with the heartbreak and sun exposure and everything. “If you ever wonder why you ride the carousel, you do it for the stories you can tell,” he reminds us. Me and Uncle Andy, we agree.

While 1978’s “Son of a Son of a Sailor” is Buffett getting borderline hokey, 1970’s “The Captain and The Kid” is a straightforward exploration of his sailor grandfather struggling with age and debility. One wonders if Buffett’s granddad was aware of the profound effect he would continue to have on young Jimmy, so long after he died. The tune describes a grandfatherly, expansive kind of love – full of hard-won wisdom and not here to judge you. My Grampa was like that too, taking his daughter and us three kids into what was supposed to be he and Gramma’s retirement home. Never complained about aging either, until the day he could no longer fish. Much appreciation for Jimmy Buffett for giving me a blueprint for grieving him, “And though I cried, I was so proud to love a man so rare.”

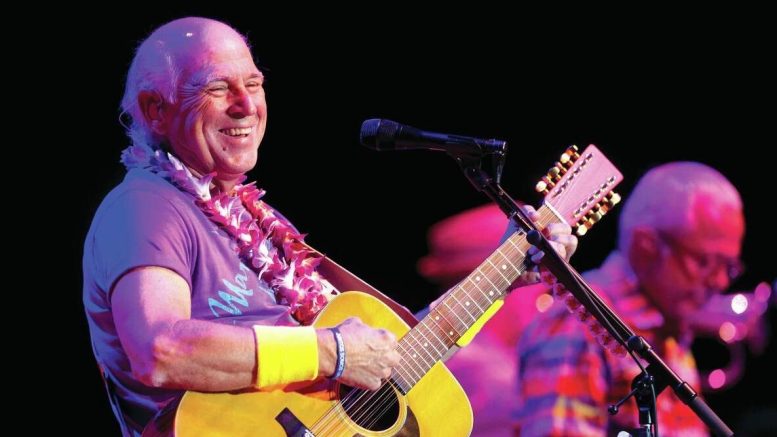

I never met Jimmy Buffett, nor even saw him in concert, but our parasocial relationship goes way back. His were the songs I knew by heart before kindergarten, helping explain a lot of what came after that. And I am not alone. Millions of Millennials knew him like that too. So, let us take an intergenerational moment and share a happy cry for a life well-lived.

Holly Calderone BS, MSW, is health educator and social worker and her song for Sacramento is “I Have Found Me a Home.”

Be the first to comment on "Essay: Jimmy Buffett was an existentialist"