With a partial agreement reached and tens of thousands remaining on strike, UC workers wonder if they can afford the work they love.

By Gabriel Thompson, Capital & Main

This story is produced by the award-winning journalism nonprofit Capital & Main and co-published here with permission.

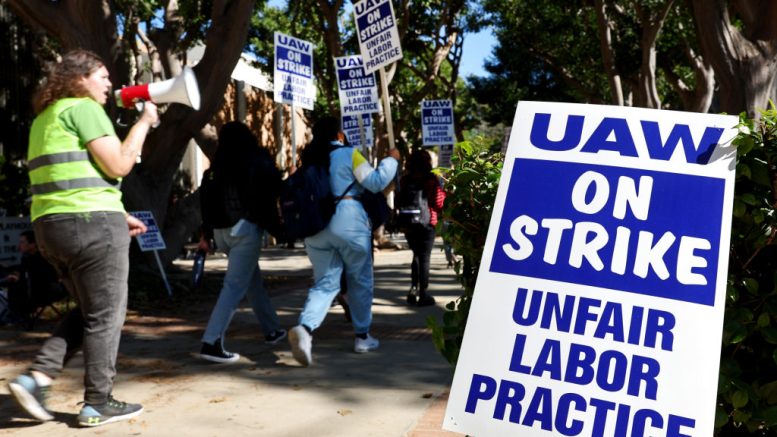

On a gray Monday morning in Berkeley, Connor Jackson, bullhorn in hand, shepherded University of California graduate student workers into buses headed for a rally in Sacramento. He’s been on strike since mid-November along with 48,000 workers in what is the largest labor stoppage in the history of American higher education.

Jackson, 29, is a PhD student in the Department of Agriculture and Resource Economics and a member of Student Researchers United (SRU), one of three separate locals within the United Auto Workers that represent UC workers. “I saw how difficult it is for graduate students to afford to live anywhere in California,” Jackson said, describing his motivations to unionize.

According to the UAW, the starting minimum annual income for teaching assistants and student researchers is around $23,000. Jackson started organizing with the nascent SRU in 2018; it won recognition from UC administrators last year after holding a strike authorization vote. While pursuing his studies, Jackson has juggled three jobs: two on campus, as a researcher and graduate student instructor, and one off campus. The low wages are “a real impediment to being able to do our research and teach effectively, but [they] also limit the number and type of people who are able to pursue graduate education and a career in academia in the first place,” he said.

The number of strikers is impressive; the employer is massive as well. As Jane McAlevey, a longtime labor organizer, fellow at the UC Berkeley Labor Center and current striking member of UAW Local 5810, recently pointed out, the UC system has about the same number of employees as General Motors did in 1947, when the UAW was at its most powerful.

Last week, UC administrators and Local 5810, which represents postdocs and academic researchers, came to a tentative agreement that would increase wages and provide additional funding for parental leave and child care. Members are voting through tomorrow on whether to accept the contract. The agreement, however, covers only a quarter of the striking workers, leaving out graduate student teaching assistants and student researchers — the very people filling the buses for Sacramento that morning.

* * *

Nelson Lichtenstein, a labor historian at UC Santa Barbara, has noted that funding for most postdocs and academic researchers is provided by the federal government — making UC administrators more likely to grant them concessions. Meanwhile the lowest paid strikers still without a deal — numbering about 36,000 — are funded directly out of the UC budget. Lichtenstein described it as “a divide-and-conquer strategy” on the part of the employer. Although the president of Local 5810, Neal Sweeney, has pledged to continue striking in solidarity with the graduate students, the agreement his members are voting on this week includes a no strike clause, likely meaning that if the contract is ratified, members would be forced to go back to work even while tens of thousands remain on the picket line.

Union surveys have found that 60% of postdocs and 92% of graduate students are rent burdened, spending more than 30% of their income on rent. Mia Antezzo, 26, is one of those graduate students, although the term “rent burdened” doesn’t do justice to the impossible economics of her situation. Antezzo works as a reader in the sociology department at UC Berkeley, a job that includes helping students with writing assignments as well as reading and grading their work. These are essential tasks at an institution of higher learning, and she enjoys the work. The pay, however, is just $17 an hour. Working roughly 20 hours a week, she brings home about $900 a month, not enough to even cover her rent, let alone food and other expenses.

“It’s been tough,” Antezzo said on Monday. “It’s hard to make ends meet in general in the Bay Area, and it’s very hard on these wages.” She fills the gap with student loans and expects to graduate with tens of thousands of dollars of debt.

* * *

As the strike enters its fourth week, workers are escalating the pressure on the UC with increasingly confrontational tactics. A few hours after speaking to Capital & Main, Antezzo joined a group of graduate students who occupied the University of California Office of the President in downtown Oakland, shouting chants of “shut it down” that echoed throughout the lobby and interrupting a meeting in progress. Meanwhile, 2,000 strikers marched in Sacramento, with 17 arrested while occupying a UC administrative office. Additional sit-ins and pickets have been held at the homes and offices of prominent UC donors and members of the Board of Regents, the governing body of the UC system.

Lichtenstein said that he had been struck, in listening to graduate students and UC representatives, by how differently each side sees the conflict. “For the UC, I think they’re looking at it as business as usual, a routine problem. They might give them an incremental increase and that’s it. The student workers see this strike as transformative,” said Lichtenstein — nothing less than a historic attempt to redefine high education and what it means to be an academic worker.

”I think there is a mindset among some faculty and the administration that we’re not really workers — that we’re just students,” said Antezzo. “This insistence that this work is just something to help supplement our education and we have to pay our dues and live in poverty is frankly really insulting, given how essential the work we do is. The labor that we provide runs the university.”

Copyright 2022 Capital & Main

Be the first to comment on "In its fourth week, the massive University of California strike reaches a pivot point"