By Sameea Kamal and Ariel Gans for CalMatters

A gift or a curse?

For Angelique Ashby, running as a “women’s advocate” in a heated state Senate race in Sacramento might be a little of both.

Her competitor, Dave Jones, a fellow Democrat, went to court to block Ashby from using that as her ballot designation under her name. His lawyers argued that it wasn’t her vocation, though it could be a profession or occupation, but that Ashby didn’t qualify.

Jones, a former Assemblymember, won his argument. But Ashby also benefited: The lawsuit fired up some of her supporters and prompted a firestorm on social media. Part of the politics: Sacramento County hasn’t sent a woman to the Legislature since 2014, and a district anchored in the county not since 2002.

For Ashby, it’s also personal: Her story of putting herself through college and law school while a single mom has been her calling card since first running for Sacramento City Council in 2010.

“If you needed a reminder, you got one today. Women are still marginalized and easily dismissed,” she said in a statement on the ballot designation decision. “But I refuse to accept that as our fate. Let this be a rallying cry. Elect more women.”

The Nov. 8 election presents a big opportunity for women. With a number of seats up for grabs due to redistricting and a wave of retirements, the number of female legislators could rise above the current record of 39 of 120 seats.

The overturning of Roe vs. Wade has also generated more energy among female voters and highlighted the importance of having women in policy-making roles — even in California, where abortion rights are protected.

Still, many women running for the Legislature for the first time face similar barriers to any political newcomer: smaller support networks, difficulty fundraising and, in some cases, targeted attacks.

Despite clinching a spot on the November ballot in one of the most-watched Assembly races this year, Redwood City Mayor Giselle Hale dropped out six weeks after the June primary, shocking the California political world.

She blamed attack ads funded by real estate and apartment associations, which were supporting Diane Papan, the deputy mayor of San Mateo.

Hale said that while she could compartmentalize comparisons to Donald Trump and manipulations to her image, she couldn’t expect the same of her five-year-old daughter, who regularly saw the ads while watching kids’ YouTube shows, or her eight-year-old daughter, whose classmate brought a negative mailer to school.

After seeing her experience, more than a dozen women told her they would never run for office, Hale said. “People were terrified to run after watching my race,” she said in an interview. “I absolutely think it had an impact on the quality of candidates, the quantity of candidates for a variety of local seats.”

Aisha Wahab, a Hayward City Council member running against Fremont Mayor Lily Mei for a state Senate seat representing Alameda and Santa Clara counties, says that as a woman of color, and as a relatively younger public official, she faces a lot of second-guessing — from the public, as well as from her own community.

Candidates like her have to answer questions about whether they’re qualified, competent, emotionally stable and “dedicated enough,” she said.

“Men don’t necessarily have to do that,” Wahab said. “Women know they have a balancing act — being firm and being strong and competent, but also soft and compassionate and sensitive.”

A similar refrain comes from Liz Ortega, a Bay Area labor organizer and mother running for state Assembly against fellow Democrat Shawn Kumagai. She says she spent years running men’s campaigns.

“They don’t get asked things like, ‘Oh, where are your kids tonight? Who’s taking care of your kids?’ when I’m out late fundraising,” Ortega said. “They just don’t get those kinds of questions, or those kinds of judgments.”

A look at the numbers

Today, women hold 24 out of 80 seats in the state Assembly and 15 out of 40 in the Senate. At 32.5%, that’s slightly above the average of 31.1% for legislatures around the country.

But that representation is far below parity, since half of Californians and a majority of California voters are women.

Of the 100 legislative seats on the Nov. 8 ballot, women are guaranteed to win 19 of them, because the top two candidates from the June primary are both women. Six female state senators aren’t up for election this year and will join them.

And if every woman facing a male candidate who led the June primary by more than 5 percentage points also wins in November, the record total of female legislators would rise to 45, according to a CalMatters analysis.

But that would still be 15 short of gender parity.

It has been an uphill climb for women in California politics. In 1975, only three women served in the Legislature; in 1980, it was only 11. But the number has steadily increased, with women holding at least 20% of legislative seats for 30 years straight.

Across America, the number of women elected to state office took off in the early 1970s during the Equal Rights Amendment movement, creating pushes for policies such as allowing women to apply for credit cards and have equal access to education and sports.

“We think about that very much as a moment when the second wave of the feminist movement met electoral politics,” said Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. “It wasn’t just about being on the outside trying to get your agenda taken care of, but it was about electing people to office to have an impact on policy so that some systemic change could happen.”

The numbers grew steadily through the early 1990s, then stagnated until 2018, when they surged again after the election of President Donald Trump.

“They saw in a very stark way, as a result of the 2016 election, the whole issue of elections having consequences and needing to not sit on the sidelines anymore, but to run for office,” Walsh said.

In 2022, California boasts several “first females” in statewide offices: Lt. Gov Eleni Kounalakis is the first woman elected to that office, while Treasurer Fiona Ma and Controller Betty Yee are the first women of color in those positions. Yet, in its 172 years, progressive California is one of 19 states that has never had a female governor.

In March, Kounalakis made history as the first woman to sign a bill into law when she extended an eviction moratorium while Gov. Gavin Newsom was on vacation. “I remain more determined than ever to ensure that, while I may be the first to do so, I will certainly not be the last,” she tweeted.

In a Monday interview with CalMatters, Kounalakis said that women still face “many challenges and barriers” to political leadership, noting that others failed in their bids for lieutenant governor. While she said women shouldn’t be coy about their ambitions, she also said there’s a long way to go before she decides whether to run for governor in 2026.

Women have also made some gains in policy-making, including on issues such as education, health and domestic violence. This past session, they helped lead a legislative effort to reduce plastic pollution, warding off a competing measure on the November ballot.

“If you don’t have women at the negotiating table, these policy issues don’t get to see the light of day,” said Ivy Cargile, a political science professor at California State University, Bakersfield. “These voices don’t get heard and they continue to be marginalized.”

Susannah Delano, executive director of Close the Gap California, which helps recruit progressive women to run, said she hopes doing so will lead to not only policy shifts, such as campaign finance reform, but a culture shift at the state Capitol.

“I think a lot of the data is there, especially through the COVID pandemic, to show that women in leadership positions do bring different outcomes, different perspectives,” she said.

A 2020 study by the National Women’s Law Center, for example, found that “greater levels of women’s representation led to greater legislative achievements” — not just for women, but for the whole legislature.

“A lot of it is our own experience. It also shapes our values and shapes, like what we fight for, right?” Assemblymember Cristina Garcia of Bell Gardens, chairperson of the Legislative Women’s Caucus, told CalMatters, citing her advocacy for environmental justice because of the toxic air in her community. “It’s not a coincidence.”

Not just gender

Women come to politics from widely varying backgrounds, and hold a wide range of views as well. Nationally, not all women’s representation is increasing at the same rate: Non-white women face greater disparities in representation than white women, despite their growing numbers.

In California, 24 of the 39 members of the Legislative’s Women’s Caucus are women of color. Based on a review of its member list, there has been a dramatic increase in representation of women of color since 2012.

But the total number doesn’t tell the whole story: There’s only one Black woman in the Senate, and only one Asian American woman in the Legislature, Garcia notes. In 2014, there were only three Latina legislators, so they got together to help recruit more. Now, that number is 20.

“As a woman of color, I know what it feels like to be the only Latina and to feel like the weight of having to be the voice for Latinas,” said Garcia, a Democrat who lost to two men in the June primary in her run for Congress. “It’s not just parity in numbers, but that we have parity in power… in the decision-making and at the table.”

There are also some differences among party lines.

While women make up 59% of registered Democrats in California, they’re only 49% of Republican voters. Of the 39 women now in the Legislature, 30 are Democrats and 9 are Republicans.

“The Democratic Party has been very intentional about ensuring that there is an infrastructure established for women to run for political office. Unfortunately, the Republican Party hasn’t been as intentional about that,” Cargile said.

Walsh said many Democratic women have made strides with the support of political action committees and women who already hold leadership positions within the party. “In many ways success begets success,” Walsh said, pointing to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of San Francisco and Vice President Kamala Harris, a former U.S. senator and California attorney general.

Some of the difference may be due to the GOP’s distaste for identity politics, Walsh said: “There’s much more of a sense that the best candidate will rise to the top, we live in a meritocracy, and whoever will be the best candidate for a community will get elected.”

Rhonda Shader, a Republican running in an Orange County state Senate race, says she can’t meet with every voter face-to-face, so she has to rely on her party designation to signal to voters that her decisions would be more conservative.

“I always hope that they’ll look beyond that, if they’re willing. But that’s off the table for some people,” she said. “They don’t want to get to know me, they don’t want to have a conversation because I’m a different party than them.”

Is the future female?

While California hasn’t seen the surge in other states of women registering to vote since the Supreme Court abortion ruling, Walsh said it’s possible that the overturning of Roe V. Wade, besides increasing turnout among female voters this year, may eventually cause another surge in female candidates.

“I think we may well see more activity, more activation, more motivation on the part of women to come out and to vote,” she said. “And then I think we’ll be watching in the next couple of election cycles to see if this also translates to candidacies.”

But to increase representation in California, Cargile said that women must be “ready in the pipeline.”

Some changes to running for office and serving in office could help make that happen.

Hale, the state Assembly candidate who dropped out, pointed out that, for women with young children, campaigning can be very difficult. It wasn’t until 2019 that California candidates were allowed to use campaign funds on some childcare expenses.

“It’s not only a sacrifice of time with your children, it’s a huge sacrifice of your resources and your money,” Hale said.

She also suggested allowing more flexibility in the hours and raising the pay of being a legislator.

During the 2020 session, Assemblymember Buffy Wicks, an Oakland Democrat, had to bring her month-old daughter to the floor for a late-night vote to pass a family leave law, because her request to vote by proxy was rejected. After outrage from working women and national figures, Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon apologized.

Jenny Leilani Callison, who is running against Democratic Assemblymember Lori Wilson in a district that includes Contra Costa and Solano counties, spoke from her hospital room last week after giving birth to her second child.

“When I decided to campaign, it was in October-November. I found out I was pregnant in February,” she said. “So it was very much like, ‘Oh no, is it going to derail it?’ But I think moms can do almost anything these days.”

Callison is a veteran who works for the Assembly’s Military and Veterans Affairs Committee. Her platform includes promoting cleaner streets and helping small business owners, but she also hopes to help improve maternal care. During the birth of her first child, she experienced excessive bleeding after delivery.

Callison says as a first-time candidate running with no party preference — and who couldn’t attend events as often later in her pregnancy — fundraising is difficult.

Another path Hale sees for new candidates is for California to match small campaign donations with public financing to help even the playing field for those without big donors.

Hale also said if interest groups were required to put their brand logos on the ads they funded, the spots would be less nasty. “They need to have skin in the game,” she said.

Shader said while it takes “a lot of courage” to run for office, government works best “when we all take a turn.”

“Somebody else needs to step up,” she said.

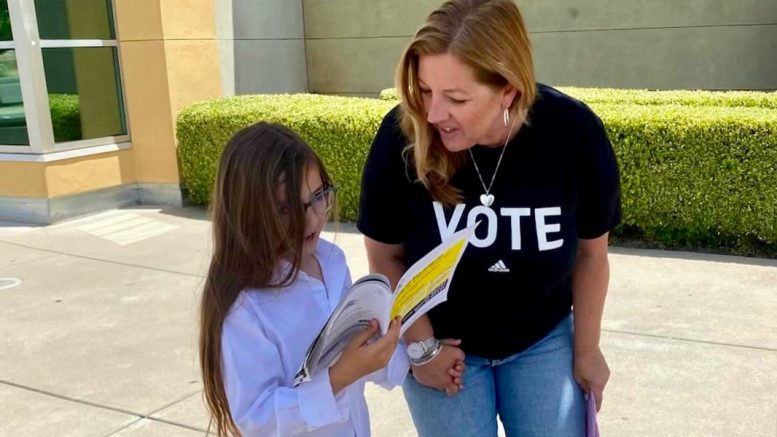

Ashby is trying. At her rally, some supporters cited her support for equal pay and her mentorship of young women.

“She’s not a politician to us. She’s a community member and a mom… interested in making Sacramento better,” said Pamela Santich, 63, a Sacramento resident.

She and her mother-in-law, Jackie, said they believe Jones’ move to prevent Ashby from describing herself as a women’s advocate will backfire.

“I think he made a mistake because he was grasping at straws and he pulled the wrong straw,” Jackie Santich said. “Because so many women in this area vote… it was not a wise choice.”

In a statement, Jones highlighted his record on women’s issues: “I’m proud of my record passing legislation giving women redress from wage and salary discrimination, preventing health insurers from charging women more than men, expanding access to safe and legal abortion and contraception and of the endorsements I have earned from leading organizations that advocate for women’s rights, including Planned Parenthood Advocates Mar Monte and NARAL Pro-Choice California.”

For the record: An earlier version of this story did not adequately explain the argument made by state Senate candidate Dave Jones against his opponent Angelique Ashby’s use of “women’s advocate” as a ballot designation. His lawyers successfully argued that it wasn’t her vocation, and while it could be a profession or occupation, Ashby didn’t demonstrate that either.

Be the first to comment on "Will women rule in the 2022 California election?"