By Kevin Taylor

At the close of the Industrial Revolution, English breeders developed a smaller, lighter toy bulldog, around 12-25 lbs in weight, some with erect “bat” or “tulip” ears while others had “rose” ears. A burgeoning trade with the French soon transpired.

In France a more uniform breed was developed—a dog with a compact body, straight legs, but without the extreme underjaw of the English Bulldog. They also had a touch of terrier personality without being snappish and snarlish and quarrelsome.

Known as “Bouledogue Français,” the toy breed with tulip ears was a great favorite with the bourgeois class as well as Parisian streetwalkers–“les belles de nuit.” Risqué postcards began to appear showing scantily clad working girls alongside their French bulldog companions. The provocative Montmartre artist Toulouse-Lautrec painted a “Frenchie” named Bouboule whose mistress was Madame Palmyre, the proprietress of the famous café La Souris.

Society folks slumming in the red lights districts noticed these lively little bulldogs with outsized personalities. The aura of notoriety that ownership of the dogs conveyed offered a fashionable way for the well-to-do classes to show off how daring they could be. They became favorites of the artistic, swagger set across Europe, and before too long they were “à la mode.”

When they crossed the pond, it was the tulip-eared bulldogs that sprang into great favor among wealthy Americans who fell in love with their compactness and their perky, bright, obedient and intelligent disposition. This roguish breed was described as “a clown in the cloak of a philosopher.”

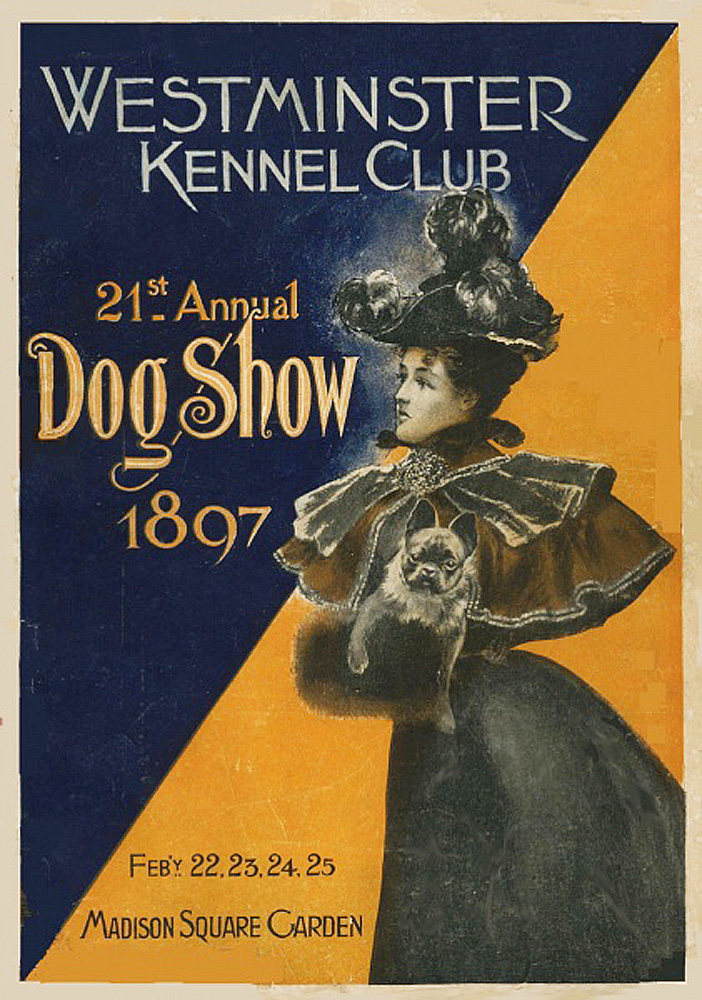

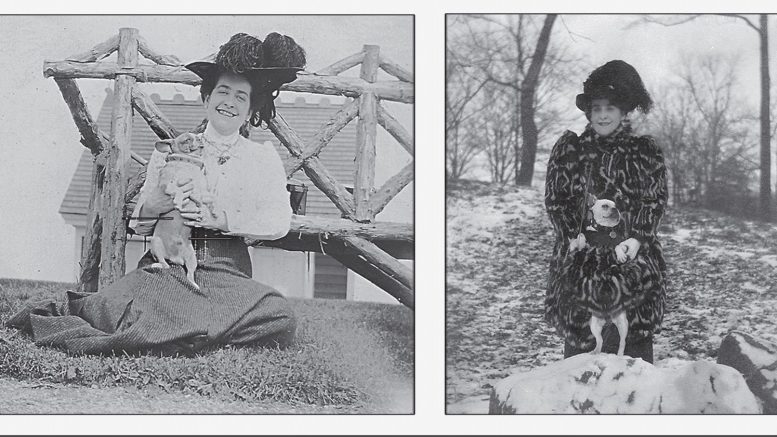

Society ladies first exhibited Frenchies in 1896 at Westminster. A French bulldog was featured on the cover of the 1897 Westminster catalog even though it was not yet an approved American Kennel Club breed. It was in ’96 that scandalous Sacramento heiress, Mrs. Amy Crocker Gillig, adopted her first brindle-colored French bulldog Pinko, who won prizes in Paris for being the finest specimen in his class. She was the daughter of E.B. Crocker, the Big Four attorney who built the Crocker mansion and art museum. Amy, the well gowned “Queen of Bohemia,” would garnish a lot of attention while giving the perky Pinko a jolly little morning walk down Fifth Avenue.

The Gilsey

In 1889, Ms. Amy Crocker and her new husband Harry Gillig spent the winter months in their suite of rooms at the Gilsey House, a luxury hotel at 1200 Broadway in what was becoming the primary entertainment and amusement district of Manhattan, with numerous theaters, gambling clubs and brothels. It would be a home base for the globe-trotting, frenetic couple throughout their eleven-year stretch with holy matrimony. It was at the Gilsey that, at the close of their marriage, Amy’s star French bulldogs Diabutsu and Dimboola lived in Gilded Age glory.

The San Francisco Examiner commented on how these spoiled little doggies dined on the same food as their mistress. They were bathed in perfumed water in their private bathroom at the Gilsey by their own dainty, skillful French maid. They slept in imported baskets on eider-down pillows and wore massive collars made of Japanese coins. Amy had their miniatures painted by the famous animal artist, Mrs. Izora C. Chandler, at $100 for each head.

While her husband Commodore Harry Gillig was winning many cups with his big schooner Ramona and other racing craft, Amy was becoming a rabid enthusiast for French bulldogs, and exhibited many of the breed in various prestigious dog shows.

Westminster

The trouble began at the 1897 Westminster Kennel Club show. The New York Times reported that English judge George Raper settled a skirmish about which flowery bulldog ears would be the legitimate and preferred in America, rose or tulip. Of the ten toy bulldogs entered, only three had the rose ears, yet they swept all the prizes including a special prize for best dog of the breed. Raper commented, “In the bulldog standard of fifty or sixty years ago it was stated that the ears might be either rose or tulip type, but the modern standard requires the rose ear. My idea is that the small bulldog should conform to the big type.”

G.N. Phelps, a Boston dog dealer and importer of the tulip eared treasures was left lamenting. His entries (none valued at less than $750 with his Monsieur Boulot being catalogued at $2,000) didn’t win any official accolades. According to the tulip lovers the winning toy bulldogs with unregenerate rose ears were ordinary. They were considered “commoners.” Judge Raper was, “not a society man, but a very plain individual,” and therefore not qualified to determined which of the bantam bulldogs were the superior of the lot. The judge’s decisions stuck in the gullet of the landed gentry to whom the Frenchies had become so dear.

The French Bull Dog Club of America was organized the day after Westminster closed its show, 125 years ago.

Nemesis George Raper surfaced again the next year. He doubled down on his claims that the tulip eared bulldogs were “all wrong.” He said that he had never seen such dogs in England or France. The breed, in fact, was not recognized by the leading French dog club–Societé Centrale pour l’Amelioration des Races de Chiens en France.

The compromise offered by Westminster was to divide the judges. Of the four classes of toy bulldogs, French and English, two were to be judged according to the standard adopted by the newly formed French Bulldog Club of America. The other two classes were, however, to be judged according to the standards of the Societé, etc., which meant that the rose ears would again have an edge in those categories.

The French Bulldog Club issued a formal statement of protest, but no notice was taken. In defiance, they withdrew their special prizes offered, and notified the Westminster Kennel Club that their appointed judge , Mr. E.D. Faulkner, would not serve.

Every Dog Has His Day

The rift between the run of the mill pure breed owning fat cats and the upper stratum of canine aristocracy became an international story that was picked up by newspapers large and small. The rebellious and unrepentant French Bulldog Club of America had the temerity to break loose from the parent stock, the Westminster Kennel Club, and boycott their show.

A meeting was called and the bulldog club decided to host an “independent specialty” in the extravagant precincts of the Waldorf-Astoria. The finest rooms in the fine hotel were allotted to the dogs, up in the sun parlors on the fifteenth floor amid potted palms, Oriental rugs and soft divans. No rosy bulldogs were allowed. In three weeks, premium lists were printed and mailed, and sumptuous arrangements were made for benching dogs and entertaining guests. It would be the season’s most exclusive event. The engraved tickets of admission read “invitations to an afternoon tea.” The little dogs were to be formally introduced to the “ultra-fashionables” in high society.

There were only forty-six dogs at the show and 500 to look on. There were six classes and seven prizes in a class. The prizes were handsome and included silver tankards, silver pitchers, cups and cash awards, besides ribbons galore.

Guests that graced the parlors included well known members of “the 400”: Mr. and Mrs. Stanford White, Mr. and Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs, Freddie Gebhard (first husband Porter Ashe’s chief rival on the turf), “King of the Dudes” Evander Berry Wall, Congressman Oliver H.P. Belmont and Elbridge Gerry, Commodore of the New York Yacht Club. The star attraction at the show was Gretel, a tiny, three-year-old, bred in the kennels of the Emperor of Austria. Gretel weighed only 7 ½ pounds, and was billed as the smallest of her breed in the world. She traveled 10,000 miles from her homeland in a handbag.

E.D. Faulkner was to judge 26 dogs and 20 bitches. Each was accompanied by their maid or groom, and no trouble or expense was spared to provide the dogs with every luxury. Decorative throne-like pedestals were provided by the owners to pose on for prizes and admiration. Fanciers competing in the various classes included Miss Virginia Fair (later Mrs. William Kissam Vanderbilt II), Foxhall Parker Keene (legendary polo player, U.S. Open golfer, pioneer race car driver and thoroughbred race horse owner) and Queen of Bohemia Amy Crocker. Eyebrows raised at the rather risqué act of women exhibiting their own dogs. Amy relished sharing the spotlight in the lavish setting with her adorable pups.

Mistress Amy won the day. Her Frenchie Dimboola, a brindle bull, won the first prize in the Junior Free-For-All and Winner’s Classes and the Faulkner Cup for Best in Show. She also won a cash prize of ten dollars. With her two other entries, Diabutsu and Mikko, Amy won the Convert’s Cup for the best kennel.

Waldorf was an amazing marketing experience for this new breed and rocketed the popularity of the French bulldog to a new high. The American Kennel Club recognized the breed officially (the uncouth toy English bulldog would never be recognized). The ever flamboyant Amy Crocker became the breed’s de-facto ambassador, leading promoter and chief conductor on their transcontinental express to superstardom. With the national acclaim of her dogs, Amy enjoyed something brand new in her life in the limelight–good press. It was brief. And it led to dire consequences.

Backlash

London’s Pall Mall Gazette ran a piece a few months after the successful Waldorf show declaring, “The British bulldog is done for… The bulldog has lost all its his grit; his name is no longer synonymous with gameness, with inexpugnable valour, and although he still keeps ahead on four crooked legs, his grin is the grin of a ghost, and his spirit is as dead as the dodo.” The age of the tulip had arrived.

The French soon saw the value in acknowledging the Frenchies so coveted by the Americans. The schedule of the Paris dog show of May 18, 1898, by the Societé Centrale provided classes for tulip and rose ears as toy bulldogs. This departure was a great victory for the new American bulldog club. One European publication declared that Dimboola, Amy’s prized pup, “unquestionably stands at the head of affairs” in international canine relations.

At home, The New York World published a damning piece with the subtitle, “Pets Live in Luxury While Poor Men Hunger for Crusts.” An itemized list of the costs of caring for the fashionable pets of high society was highlighted next to the lessor cost of supporting a child in need at the Children’s Aid Society and the Foundling Hospitals.

Playing off a gossip column “The Chaperone,” in The New York Evening Journal that arbitrarily placed the value of Amy’s bulldogs at 10K a head (335K per dog today), West Coast publications embellished and showcased the expensive pampering that Amy’s dogs enjoyed:

Mrs Harry Gillig, owns three $10,000 dogs and spends as much upon their food and blankets, medical attendance and luxuries that would support several families.

The dogs daily regimen corresponds to that of their mistress. They tumble out of their beribboned baskets when they hear her stir at 9:00 o’clock. Their breakfast is served when hers is, and consists of the same food. At 10:00 o’clock they go out for their airing. Patrick, their own footman, taking them in leash.

Each dog has eight blankets and a raincoat, the outfit being ordered from England. Their boots are dainty, leathern things from Paris. The minimum cost of the seasons wardrobe is $100 for each pet.

The only concession to their caninity that is made in their diet by Mrs Gillig is an occasional dog biscuit. They are permitted to eat the costliest candy and Dimboola, the star of the aggregation, does not disdain champagne.

These canine exquisites are fed from cut glass bowls and the most delicate china. They have a porcelain bath tub in which their daily plunge is taken, and they have violet toilet water sprinkled over them until they smell as dewily fresh as the flowers themselves. Lucille brushes and smooths their coats as tenderly as though they were a baby’s soft ringlets, and they court happy dog dreams in baskets padded with sachets and ornamented by bright bows and interlacings. They have sat for New York’s famous animal painter, Ivora Chandler, and had their miniatures painted on ivory just like great men and beautiful women do.

Not all of middle America was pleased with the decadence of the blue bloods and their pure breeds. Another Kansas publication Appeal to Reason, the largest-circulation socialist newspaper in American history, took direct aim at Amy and the Waldorf gang after their exclusive Frenchie show comparing their decadence to the prophesized days of tribulation. An inflammatory article described what was believed to be a treacherous trend of the nation towards plutocracy. Crocker and the dog fanciers were thought to be a natural product of a system whereby men can gather so much wealth that they, “can throw away thousands on pet poodles just as they did in Rome before she fell [while] men, women and children sink into deeper and deeper pits of woe and want.” The article went on to chastise the country’s working classes who, “refuse to raise a hand or vote to change the social structure that has produced the awful results.” The article concluded with a prediction, “In the coming century the people will wonder at the stupidity of their ancestors who could not see the causes of such inequality, just as we today see the enormity of our ancestors supporting kings and tyrants with their lives, while all the time they are oppressed by them.”

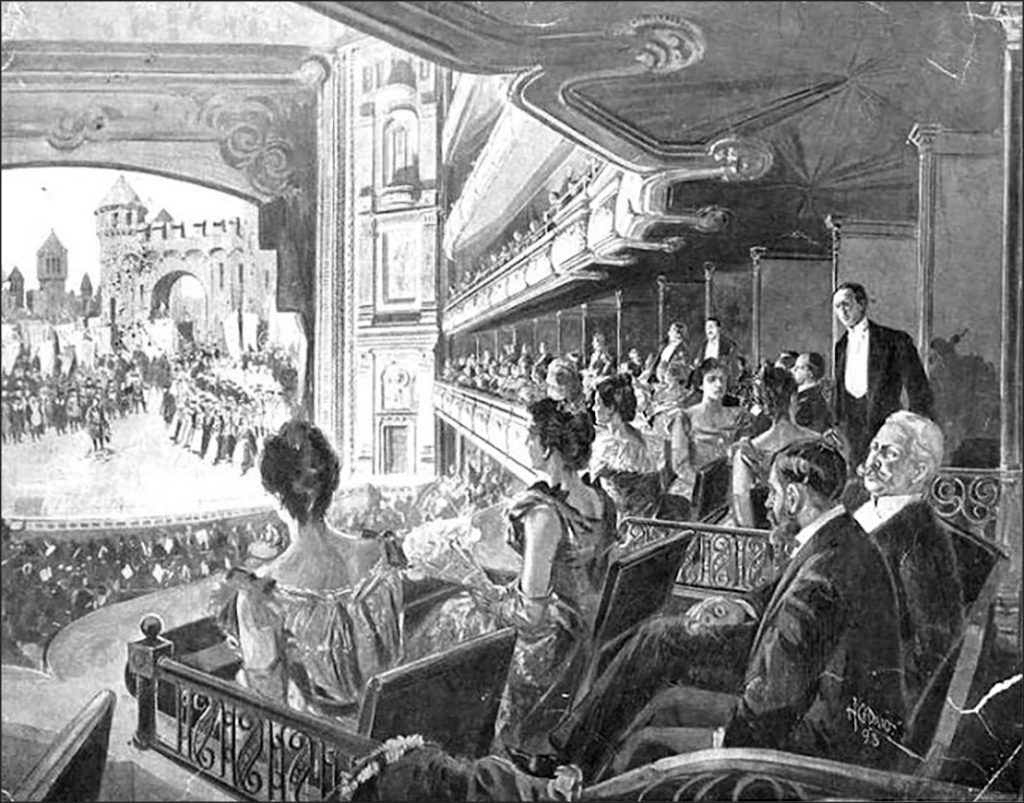

The Opera House

Westminster had no choice but to include a new French Bulldog class in their 1899 show. Amy and Dimboola would take Best Dog in Class three years running at this grand-daddy of all dog shows at Madison Square Garden. They also won at Sherry’s and Logerot Garden and at the Terrier Bench Show at the American Horse Exchange arena. The crowds of onlookers grew as did the number of canine competitors with their “cobby” bodies, tulip ears, retrousse noses and very short fat tails.

The annual bench show of the American Pet Dog Club of America was held under the chandeliers of the Metropolitan Opera House in Manhattan. The Four Hundred had many representative entries in the different classes. Amy entered side partners and kennel companions Antoinette and To To who glimmered and shined next to star attraction Dimboola. To To was brought over from Paris, where she carried off first honors and won the James Gordon Bennett Cup as the best bitch of the year.

Amy also entered Ko Hai, a (lowly) toy English bulldog that she bought after Waldorf and after one of her Frenchies died. She lavished Ko Hai with love at her expanded kennels on the grounds of her Larchmont summer home on the Sound. She joked that she had to teach him some French so he could communicate with the other dogs.

Though the ranks of the middle classes were well filled in the Metropolitan (even some proletarians showed in noticeable numbers), it was a blue blood event with record numbers of women and men, mostly opera subscribers, conspicuously hifalutin in their magnificence of war paint and decked in full evening dress. The hostesses of the boxes included actress Anna Held, interior designer Elsie De Wolfe, and Mrs. Stanford White, wife of the famous architect. The backdrop of the stage was a forest glade used in “La Sonnambula” and “Lucia di Lammermoor.” Alcoves in the wings were used to give the finishing touches to the dogs’ toilette before he faced the judges. According to The New York World, “the crowd listened to the flutelike tenor of Ali Baba the Pomeranian and the sweet soprano of the black pug prima donna Candace,” while they watched the dance of the poodles.

Next to that article illuminating the extravagant event The World strategically placed a sad story of child poverty: “Thousands Starve in NYC, Mortality Among Children Largely Due to Lack of Nourishment.” Of the 1700 children that had been received at the city morgue during the year 70 per cent or 1,200 had died of malnutrition, or marasmus, virtually starving to death.

Ninety-four French bulldogs were judged in the competition. Mrs. Gillig’s Frenchie Antoinette won the blue ribbon in the winner bitches class. In the team “Best Four” class of French bulldogs, Mrs. Gillig also won first prize, entrance fees and a medal for the best team.

The barking roar of the crowds reached a crescendo. Amy and her four-legged friends, again showered with love and affection, were by all measures a favorite of high society. Not in her wildest, saddest or most horrific nightmares could Amy have anticipated the canine catastrophe just around the corner.

Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

In October of 1900, the wealthy communities of New Rochelle, Larchmont and Mamaroneck on the Sound in Westchester County were devastated and panicked when estates were invaded by a diabolical deviant hunting down red and blue ribbon pure bred dogs and poisoning them.

The blue ribbon bull terrier Billy, which was owned by Miss Alice Steuerwald of Larchmont, was murdered as was an Irish setter owned by President Joseph Bird of the Manhattan Savings Institution. Actor Francois Wilson’s large St. Bernard watch-dog Dan was killed. Frank R. Hardy, chairman of the regatta committee of the Larchmont Yacht Club, was mortified at the murder of his brindle bull terrier. A litter of bull terrier puppies owned by Mrs. Pryor of Larchmont were fed lethal doses of arsenic.

Mrs. Amy Crocker Gillig’s fine kennel at her Larchmont home was attacked by the serial murderer who poisoned four cherished French bulldogs including the prizewinning Parisian To To. The grief stricken Amy immediately ordered her servants to bring all of her dogs back to the Gilsey House.

Dr. J. P. Nestler, a veterinary, who attended most of the stricken pets, said that they died in agony from arsenic poisoning and the consumption of powdered glass. Rewards public and private were offered by the Manor authorities of Larchmont for the arrest and conviction of the serial murderer. Servants were armed and were instructed to shoot the poisoner if he was caught committing his crimes. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) was asked to aid in the capture of the murderous reprobate.

Amy had recently discharged a kennel master. He was questioned, but was never charged.

Later in the month valuable dogs owned by residents of the Bay Ridge neighborhood of Brooklyn were murdered. Among those who mourned the loss of pets: Mrs. John Bergen who lost her toy spaniel, John Edwards lost his greyhound and Mrs. Frances Patterson lost her English bulldog.

In December, no less than fifteen dogs fell victim to a canine slayer in Hicksville, NY, not far from the Westchester round of dog murders.

1900 was a terrible year for champion pure breeds. In January, the start of the new millennium, thirty-one expensive dogs were poisoned in Berkeley in as many days. At Westminster’s 24th competition in February, two champion dogs, Highland Mary and Delaware were poisoned at the show. Similar incidents of valuable dogs being killed occurred in cities around the country including South Hampton, NY; Clifton, NJ; Dalton, PA and Appleton, WI.

In Spokane, Bismarck, Racine, Pittsburgh, Jersey City, Modesto and Stockton more kennels were attacked. Motives were always mysterious and the criminals were rarely captured.

The Westchester hit man that killed Crocker’s canines was never found. Intentional poisoning of pets was somewhat common at that time. The culprits were usually angry neighbors or burglars who wanted to silence noisy pets. The motivations behind these wanton attacks targeting thoroughbred dogs and the outrageously wealthy dog fanciers who loved them was never made known though class warfare was certainly surmised by some.

Amy’s divorce from Harry was finalized in December of 1900, just weeks after the chilling tragedy. Her engagement to Jackson Gouraud, a 26-year-old ragtime songwriter, was announced two months later right after the close of the 25th annual Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show. Amy and Dimboola entered and won one last time. Amy’s hasty third marriage in May to the vaudeville man nine years younger than her caused a scandal in New York society (songwriters were “upper-servants” at best). Young Jack, it seems, lacked the right breeding. In June, Amy was outed as a woman with tattoos in a full-color feature in The New York World. The controversial Crocker was put in the dog house with high society. She would never again return to their graces.

The heiress continued to adopt dogs–terriers and Pekineses, St. Bernards and greyhounds. And bulldogs–both French and English. Amy also adopted two “foundlings,” Yvonne and Reginald, while visiting Europe in the spring of 1899. She would adopt two more girls later in life, Dolores and Yolanda.

Ambassador Amy Crocker would be pleased to know that the French bulldog is currently the second most popular breed in America just after Labrador retrievers according to American Kennel Club rankings. She remains perhaps the country’s single most influential promoter of the breed.

Today Frenchies sell for anywhere between $1500 and $3000.

The French bulldog has never won Best in Show at Westminster.

Kevin Taylor is the official biographer for Aimee Crocker and a leading researcher on the Crocker Family. His many articles can be read at aimeecrocker.com. SN&R thanks Lionel and Daniel Milano, Aimee Crocker’s grandchildren, for the photographs of her by her kennels and in Larchmont.

Be the first to comment on "Looking back: A Sacramento heiress and Murder on the French Bulldog Express"