By Scott Thomas Anderson

For the moment, Nancy Neilson escaped danger.

In mid-December, as the weeks of spine-bracing fog gave way to rapid downpours, Neilson knew that she had to leave her camping spot near Richards Boulevard. She’d been there because of a warming center at the Union Gospel Mission on Bannon Street. She said that sanctuary eventually closed its doors, leaving her and dozens of others camped out in the industrial zone preparing for the worst.

Anyone who’s lived outdoors knows that fast-driving showers soak straight through tent fabric. More worrying for Neilson: the place where she hunkered down had been deluged by street flooding, a threat that boiled over after garbage clogged a storm drain and sent water coursing under a long row of tents.

“It feels like arctic weather, literally,” Neilson said. “It’s stinging. When I’m outside, I feel completely frozen.”

When the chilling winds get strong, Neilson thinks about the winter of 2022-23 – and about the five unhoused Sacramentans who died in one storm-battered season. Two were killed by falling trees. Neilson assumes the rest were taken by frost and exposure.

“It was because they couldn’t keep warm or dry,” she reflected. “They were wrapping themselves in plastic and stuff, and they were dead in the morning.”

Dwelling on those ghosts of Winter’s Past, Neilson lightrailed across Sacramento’s urban core to Bradshaw Road, where the county and First Steps Communities opened a large warming shelter. Inside an inviting auditorium, Neilson was offered cots, regular meals and hot showers.

“A place like this is a blessing. It’s really nice,” stressed Neilson, who remained safe in that warming center through the holidays.

Fifty miles to the east in the city of Jackson, Cynthia Hale was having a very different go of things the night after Christmas.

The 51-year-old and her dog Gypsy were fixtures in the historic mining community. Hale had reportedly lived a fairly average existence in the area for decades. About 10 years ago, her fortunes turned, which led to sleeping on Jackson’s century-old avenues. Gypsy had been Hale’s tail-wagging companion through the thick and thin of this new existence.

Friends say Hale was known for striking up chatty conversations with the locals and never asking anyone for money. Many in the city’s unhoused community appreciated that she would always share what food or supplies she had. “If I got, you got,” is what Hale would always say to others trying to survive the outdoors.

Over the next forty changings of the season, Hale and Gypsy were part of Jackson’s everyday rhythms.

Hale’s unbreakable bond with Gypsy was one reason it was difficult to get her into shelter, said Trixxie Smith, a peer support specialist with Sierra Wind Wellness and Recovery Center in Jackson. Years ago, Smith herself experienced homelessness in Sacramento, which gave her first-hand knowledge of how living outdoors takes a physical and spiritual toll that almost bends time itself.

“She was on the streets the entire 10 years that I knew her,” Smith said. “And 10 years on the streets is a lot more than 10 years. I watched Cynthia deteriorate, little by little, from being out there … I know that about 12 months ago, she started having seizures. She was very afraid of having a seizure in her tent, alone in the middle of the night, with no one knowing what was happening. Cynthia fell into a routine where she would end up in the hospital, but then she’d check herself out because she wanted to get back to her dog. She would say, ‘Gypsy needs me,’ and ‘No matter what, I will never leave my dog.’”

Around 5 a.m. on Dec. 27, one of Hale’s friends discovered her motionless by an old telephone booth at a Chevron Station near Jackson’s main street. Gypsy was nowhere to be seen. An arriving Jackson police officer started CPR on Hale, continuing until medical responders took over.

It was no use.

The Amador County Coroner’s Office is still determining the cause and manner of Hale’s death.

Those close to Hale say she was a veteran of enduring harsh winters in the Sierra foothills. Responders found her wearing multiple layers of warm clothing, and so some friends doubt that she literally froze to death. But for those who cared for her, that’s not the point: What saddens them is that Hale’s last moments on earth were spent feeling the inescapable ache of winter’s darkness — and that her last sights were of lonely, blinking neon and empty, shadowed streets.

Following Hale’s death, Gov. Gavin Newsom proclaimed major progress in combating homelessness in California, though he used early and incomplete data to make the assertion. At that same moment, Newsom was unveiling some $419 million in new grants for congregate housing, interim youth housing, permanent supportive housing and mental health navigation centers, all of which would be focused on the regions of Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco.

What Newsom did not announce was any new law or regulatory framework for mandatory and fully funded warming centers across the state, places that could save individuals from weather-related death and keep severely ill people like Hale connected to immediate medical response in case of emergencies.

On New Year’s Eve, people crowded into Rosebud’s Café in Jackson for Hale’s celebration of life. Tyx Pulskamp, a server at the café who has also done homeless outreach for years, eventually took up the microphone.

“I know folks are concerned about Gypsy,” Pulskamp began, “and I just wanted to relate that she’s safe, and warm and being fed by the people who work at our animal shelter, people who have known her, and have loved her, and who’ve released her many times before — without fees — so that Cynthia and Gypsy could be together after instances of hospital visits.”

Choking back tears, Pulskamp added, “For folks who have been in that position, and wondered how their dog is, my contact at the shelter has shared that she is well.”

Sarai Miser, a former hotel worker who’s been homeless for a year, was looking on from one of the nearby tables.

“She really was a very kind person,” she said of Hale after the service. “She was the one person who could approach me when I was not feeling very good, or hating my life out in the streets, and just check on me to make sure that I was OK. A lot of times, she might have saved me from doing something – I mean, she pulled me out of some deep, dark depressions.”

Miser added, “It’s bone-chillingly cold out there in a way that I can’t explain: As soon as it gets dark, and the mist comes in, it’s just so cold. I felt my heart tighten the other night — and the next day is when I found out Cynthia was dead.”

Counts, cold spells and harsh realities

A white mist glided over the American River, its pale cloud separating gaunt oak trees from their reflections on the frigid water. Down the way, a group of people were leaving the city of Sacramento’s warming center on North Fifth Street and venturing out into a new, brisk morning.

This respite spot had been opened for several days because of low temperatures, but it was now reclosing. A woman with a walker scooted her way through its doors, her breath instantly visible against the early sunrise. A man in a wool cap, heavy jacket and yellow mittens inspected a tattered scarf next to his bike. More people filtered out, many shuffling toward the nearby embankment where a lone tent stuck ahead of the milky fog that rode the river.

That was one of two warming centers that the city of Sacramento intermittently activates during perilous weather conditions. So far this winter, between the two sites, they have served a combined eight and 44 people on each of the 16 nights that they were open, according to local officials. The large Bradshaw Road warming center that Nancy Neilson found safety in, which was operated by Sacramento County and First Steps Communities, offered shelter to roughly 85 people each night it was operating.

That facility also has homeless outreach workers who specialize in connecting clients to health services, long-term shelter or permanent housing. City officials said that people who enter their two weather-respite centers become part of their case management system, which makes it easier to receive more services.

Funding such “wrap-around services” was a big part of Newsom’s announcement on Jan. 16 when he declared California had experienced a 9 percent drop in unsheltered homelessness in 2025.

“We put Proposition 1 on the ballot because Californians are demanding we do more to confront the mental health crisis and the homelessness emergency head-on,” the governor told reporters. “Voters gave us the tools and we are putting them to work, delivering treatment, housing, and real support, and proving that this state can lead the way on a challenge facing the entire nation.”

Newsom added, “Our state investments have launched critical programs for local communities. Together, we’re breaking cycles of homelessness that took decades to create — and we’re doing it with urgency, compassion and accountability.”

Yet, by the admission of the Governor’s Office, the alleged 9 percent drop in unsheltered homelessness is based on preliminary “regions reporting 2025 numbers” for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s point-in-time counts.

At the time that Newsom made his proclamation, those bi-annual HUD counts for unsheltered homeless had not been fully completed, including in Sacramento County, not to mention Amador County where Cynthia Hale died. The San Francisco Chronicle also clarified that the overall number of homeless Californians remains higher today than it was in 2019.

Six days after Newsom’s presentation, the homeless point-in-time count for Jackson was actually happening. Unhoused individuals gathered at the city’s mobile shower program. Christine Platt, the city’s Homeless Outreach Coordinator, worked with several volunteers to interview those who showed up for hot water, food and warm clothes. A specialist from Amador County’s behavioral health department was also present, along with two representatives from Insight Housing, which offers outreach efforts for veterans.

Some locals in Jackson say that interest in volunteering for homeless support has gone up since Hale’s passing. But for Miser, who allowed herself to be tailed for the P.I.T. count before taking a shower, whatever surge of interest there is now hasn’t made finding a job or affordable rent for her any easier.

“I didn’t think I’d be out here this long,” Miser acknowledged. “When you look up ‘community,’ the definition is people with related interests in a common area. That definition has nothing to do with what you own. Just because I don’t own a home doesn’t mean I don’t want to thrive, or be successful or move forward with my life.”

Real people, real stories

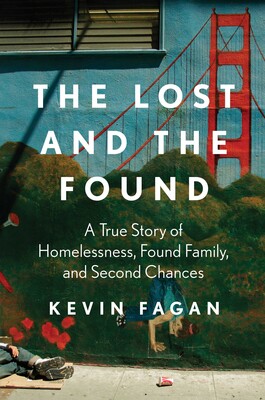

Over a three-decade career, Kevin Fagan captured the sustained stress of existing on the periphery. While talent and experience made Fagan the go-to reporter at The San Francisco Chronicle for homelessness, it was his own teenage struggles that gave him a personal decoder for how unforgiving the streets truly are.

Fagan recently published “The Lost and the Found: A True Story of Homelessness, Found Family, and Second Chances.” Years in the making, the book doesn’t shy away from the numbing complexity of America’s most uncomfortable topic.

Fagan may have been preordained to dedicate his life to journalism. His mother, Doris Lee, was a reporter and editor for the U.S. Navy during the Korean War. She specialized in telling POW survival stories. Fagan remembers his mom mentioning an American prisoner of war who had escaped his guards by running out onto a field of snow.

“His feet got frost-bite, so he had to crack the bones off his toes and tear them out, so they didn’t get in the way while he was running,” Fagan noted of the story. “When she first told me that, I was about eight, and I thought, ‘Wow, I want to write stuff like that.’”

Fagan started chasing that dream at his high school newspaper in Livermore. By then, he was having frequent clashes with the “tough as nails” military veteran who was his landlord — and also his mother.

When Fagan turned 16, his mom threw him out of the house.

The aspiring reporter was homeless.

Having honed his couch-surfing abilities, Fagan was able to rent an empty garage for temporary shelter. He worked and saved money. Eventually, Fagan bought a Volkswagen Bug, which gave him another place to sleep whenever there was no bed. He remembers using gas station bathrooms to manage his hygiene. Despite the instability, Fagan was steadily getting through college. By the early 1980s, he was a fully housed journalist and getting his initial taste of writing about street life in Lodi.

“The experience of being poor, and being homeless — though it was in brief periods, thank God — made me want to explore it as a reporter,” Fagan recalled.

After hammering out more homeless stories for The Oakland Tribune, Fagan took a job at The San Francisco Chronicle. In 2003, he was put on a special mission that would eventually change how political leaders understood homelessness for years to come: It involved Fagan living alongside the people of San Francisco’s sprawling outdoor encampments.

“I wasn’t scared of the street,” Fagan said. “A lot of people had lost interest in homelessness. We were in compassion fatigue; but the managing editor at the time, Robert Rosenthal, said, ‘No.’ And he had me, and a photographer named Brant Ward, stay in the streets for six months.”

Fagan and Ward’s encounters led to the newspaper series “Shame of the City,” which gained national notoriety and shined an early spotlight on the effectiveness of supportive housing. Fagan says the series found readers across the political divide. It wasn’t long before President George W. Bush’s national homelessness czar Phillip Mangano was sharing “Shame of the City” with leaders across the nation.

Prioritizing permanent supportive housing eventually became a condition that local governments had to meet if they wanted to receive certain federal funds for homeless support.

Meanwhile, Fagan and Ward were christened as one of the first fully dedicated homeless teams in newspapers.

Years later, with Fagan’s retirement approaching, he penned “The Lost and the Found.”

The book follows Rita and Tyson, two unrelated people, of different ages and backgrounds, struggling with addiction in S.F.’s encampments. Fagan first met Rita during the same year that he wrote “Shame of the City,” back when she was a denizen of what was known as Homeless Island. Tyson was someone Fagan encountered much later, in 2019, while reporting on a clash between NIMBY forces and shelter priorities around the Bay.

Their childhoods, professional histories, family dynamics and health struggles are all deeply explored, vivifying the journey both took into the streets, as well as the bonds they formed after ending up there. At its heart, “The Lost and the Found” is a duo rescue story, since Fagan was present when Rita and Tyson’s loved ones staged bold interventions. In each case, he witnessed a tenuous attempt to get someone help before their story ended with irreversible tragedy.

“With this book, I just let my heart lead me on it,” Fagan said. “These two individuals, and the people around them — and all of their experiences — stood out to me as emblematic in a lot of ways. Basically, a distillation of so many things that I had written about over the years.”

Fagan added, “And with these two people, I found so much to really like about them, and be inspired by — their families were so strong and so loving.”

Asked why the topic of homelessness feels so overwhelming to many Californians, from the lack of a statewide winter warming strategy to the heated battles that erupt on neighborhood social media pages, Fagan has developed some thoughts over the last three-plus decades.

“Nobody really likes being around despair, and frustration and illogical behavior,” he stressed. “People generally want to create a peaceful life for themselves, one that’s happy and free of conflict and want. That whole thought process is almost subliminal for your average person. So, they don’t want to be around things that are hard to understand and digest.”

“But the people living those things,” Fagan said, “they don’t want to be around it either.”

Despite all the misery he’s witnessed, Fagan also believes it is important to recognize all of the Californians who work on combatting homelessness every day. Whether government and nonprofit workers or those who are volunteering their time out of a sense of purpose, he has seen first-hand there is a dedicated phalanx of people who won’t let society give up on the problem.

“We do have some bedrock values that are compassionate,” he affirmed. “But, there’s enough of the opposite mentality that it really complicates it.”

Fabulous piece, Scott! I am forwarding to many