By Angie Eng

It takes a crisis to uplift us from the abyss. When despair engulfs, human kindness emerges. Contrary to a Hobbesian world vision popularized by films like “Soylent Green” or “The Road,” humans in crises don’t always descend into chaos and violence. When we hit rock bottom, humanity often leans into philanthrōpia or kindness and benevolence.

In the United States, the high level of individual generosity for the arts ($25.2 billion in 2023) compensates for a government that chronically underfunds culture, forcing creative institutions into a constant state of crisis and potential closure.

In calamities like the Great Depression and World War II, humans demonstrated prosocial behaviors like cooperation, solidarity and empathy when witnessing great suffering. If you were around Manhattan in the days after 9/11 you may have experienced the transformation of New Yorkers from Doberman Pinschers to Labrador retrievers — gone were the growls. Shouts and shoves were temporarily replaced by a gentler side, always there but perhaps suppressed by the city’s cutthroat competition.

Natural disasters also mobilize people to tap into their generous side. The January 2025 FireAid benefit concerts in Los Angeles raised over $100 million following the destructive wildfires that tore through parts of Los Angeles County earlier that month. Hours after the 2024 flooding in Valencia, Spain, tens of thousands of locals self-organized to clean up the streets and distribute food and water. Of course, looters and price-gougers exist, but they are the exception.

This outpouring of generosity is not limited to disaster relief — cultural institutions also rely on public goodwill during crises, as seen in philanthropy for the arts.

During financial crises such as the Great Recession and the COVID-19 recession, the stock market plunged to 26–50%, and local governments slashed cultural budgets. Private foundations, whose endowments fluctuate with the market, suffered severe losses — making arts funding precariously tied to economic cycles. During recessions, philanthropic giants Ford Foundation, Mellon Foundation and the Getty Foundation had to shift their reduced budgets to support rescue funds to prevent the closures of national museums, art schools, theaters and performance halls. The Ford Foundation & the ArtPlace America Initiative provided $150 million to save artists and cultural institutions from collapse in 2010-2011.

Despite market fluctuations, individual philanthropists from the entertainment industry like Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, Elton John, Leonardo DiCaprio and Oprah Winfrey have donated millions toward culture. Recently, billionaire businesspeople have rescued California art institutions: real estate magnate Eli Broad pledged $1 billion to Los Angeles art institutions. David Geffen and Paul Allen, the late Microsoft co-founder, have gifted more than $100 million.

As government funding for the arts faces drastic cuts, private philanthropy has become even more critical. Private donation amounts are unstable but may be our only alternative besides ticket sales for supporting culture in the future.

In 2017, during his first administration, President Trump attempted to eliminate the federal arts program, the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA). Its current budget remains at $209 million, but risks future cuts from the current administration. That is equivalent to each American contributing 63 cents for the arts per year, or what you’d toss into a fountain to make a wish like, “I wish we valued arts in America.”

To put it in perspective, culturewise, this past year Germany spent $189 per person (total budget of $14.4 billion) and France spent $74 per person (total budget $4.6 billion). For those wondering where federal tax dollars go, consider this: In 2024, the U.S. allocated $852 billion to defense — equivalent to each American contributing $2571 per capita — while the arts budget dwindled to mere cents per person. This skewed budget symbolizes our elected leaders’ priorities and inadvertently shapes our societal values. Judging from the declining NEA budget over the past 40 years, media outlets and cultural leaders may have failed to disseminate a convincing story that explains why we need art in our lives and cities.

Why art is essential

A popular argument for financing culture in the United States adheres to economic capitalist principles. The success of an arts program is based upon revenue-producing metrics like its impact on tourism, new businesses and individual wealth creation. One major concern of this strategy is it favors box-office hit entertainment over cultural experiences that spark critical dialogue and confront difficult topics.

Another issue of this neoliberal framework is it encourages creatives like poets, sculptors and dancers to shape their work into profit-generating businesses. A poet applies their writing skills to advertising jingles. A wood or marble sculptor invests their talents into furniture-making and cabinetry. A contemporary dancer uses their training to be a Zumba instructor or Las Vegas showperson.

If artists share their talents prioritizing dollars over expression, art risks losing its intrinsic values such as community responsibility, empathy and critical thinking. While we operate within a capitalist economy, not all aspects of life need be measured by revenue. Love, spirituality and happiness offer far more meaningful indicators of human impact. Throughout history, thinkers have debated why art is vital to people and society.

Aristotle and Nietzsche believed theater to be cathartic because it provides an outlet for people to process their emotions and have a deeper sense of awareness of self and others. Philosophers Thomas Aquinas, D.T. Suzuki and Chuang Tzu stressed the capacity of art to manifest the human spirit, as in the work of Leonardo Da Vinci, William Blake and Mark Rothko.

Contemporary theorists like Joseph Beuys and Nicolas Bourriaud highlighted art’s collective potential to catalyze debate and bridge communities. The Japanese Gutai movement, The Lebanese Atlas Group and the Sacramentan Royal Chicano Air Force exemplify how art engages community members as a tool for social activism. In the nation’s current state fraught with division and loneliness, community art collectives build solidarity and unveil our cultural blindspots.

These great minds and artists have illuminated a truth: Stories are our collective currency exchanged, transmitted and inherited. They are testaments to the progress of civilization. Yet, too often, art is dismissed as a decorative excess or an extracurricular activity to be cut when resources are low, but there is a solution that can bring us together.

For centuries, philanthropists have stood as cultural leaders, embodying our faith in those stories that unite us. One of history’s most revered artists, Michelangelo might never have completed some of his masterpieces without the support of patrons like Lorenzo di Medici who financed his education, studio and connected him to more patrons. Today, philanthropists continue to donate to museums that house his work knowing their support is an investment in the persistence of culture.

Cultural crisis

Yet, not all art-making is for the common good. There lies a dark side of art implementation — its weaponization. Over 2,000 years ago, Plato anticipated how art is so powerful that if misused it could be detrimental to society and manipulate the masses. He reasoned that in the wrong hands, poetry and theater could very well recount stories that create more harm than good. History offers grim illustrations of this in the form of art propaganda as in Mao’s Cultural Revolution Opera, Hitler’s Nazism and Stalin’s Communism in film, architecture and painting.

Pushing a political agenda through the arts is not a relic of the past; under the new administration, the arts find themselves under the crosshairs.

Last month, Trump took control of the Kennedy Center — an ominous act echoing Plato’s warnings about art as a tool for manipulation. In addition, Trump’s executive order on Jan. 20 to censor the arts and universities through defunding policies is a harbinger of art used by dictators of the past. The erasure of our right to free expression, coupled with the hostile seizure of the Kennedy Center, sets off alarm bells. This isn’t just policy; it’s the groundwork for a machine of ideological control, where art is no longer a mirror of society but a tool for mass manipulation.

Fortunately, humanity shines when faced with adversity during both manmade and natural crises.

In Sacred Economics, author Charles Eisenstein cautions that a society intent on commodifying every facet of human existence — love, education, family, spirituality, health, friendship and art — will eventually reach a point of profound decline. Eisenstein suggests a gift economy to cultivate connection and community that harmonizes with our innate benevolent nature. It is a system where people exchange goods and services based on generosity, reciprocity and social relationships. It is also a mindset that pivots away from perceiving people as consumers to be indulged, to viewing them as potential galvanizers responsible for shaping the cultural arts in our cities.

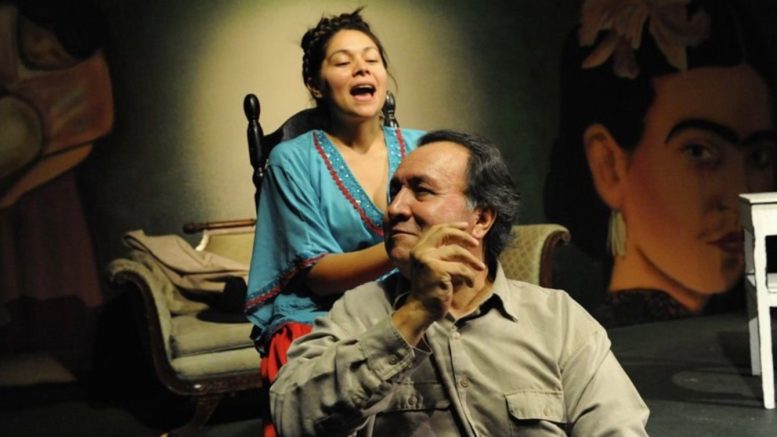

These philanthropists offer gifts and enrich their community by attending a performance or fundraiser, volunteering at a museum or theater, becoming members of independent cinemas and donating to local nonprofit cultural organizations. In Sacramento, one can easily be a patron of the arts or a philanthropist by supporting, for example, small theaters producing local talent like Big Idea Theatre, The Ooley, California Stage, Resurrection Theatre and Teatro Nagual.

In a gift economy, cultural engagement is more than a transaction — it is an act of solidarity with a concert, museum or theatre ticket acting as a glue that strengthens the bonds between artists, audiences, the city and our nation.

Sacramento native Angie Eng is a conceptual artist and educator who has lived in New York City, Paris, Mexico, and Ethiopia. She holds a Ph.D. in intermedia arts, writing and performance, and has received over 50 grants, commissions and residencies for her creative work. She teaches at New York University and is an independent writer for Solving Sacramento and Artist Organized Art.

This story is part of the Solving Sacramento journalism collaborative. This story was funded by the City of Sacramento’s Arts and Creative Economy Journalism Grant to Solving Sacramento. Following our journalism code of ethics, the city had no editorial influence over this story. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, Capital Public Radio, Outword, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review, Sacramento Observer and Univision 19. Sign up for our “Sac Art Pulse” newsletter here.

Be the first to comment on "Philanthropy in the abyss: Why we need to give when things fall apart"